A squid, startled by the presence of ROPOS descending to the sea floor, reacts defensively by squirting ink at the ROV. Click image for larger view.

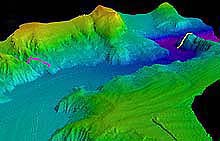

Three-dimensional image of Astoria Canyon looking west. Click image for larger view.

Into the Abyss

Richard Hill, The Oregonian, July 11, 2001

Summary: In a new national program of oceanic exploration, scientists study the deep underwater trench called Astoria Canyon off Oregon's coast.

The startled squid finds itself caught in the headlights of an unfamiliar intruder. In a flash, the cephalopod spurts ink in a bid to confuse the refrigerator-sized alien. On a research ship a half-mile above the squid's domain, scientists let out a delighted "Ho!" as the swirling blast of ink flashes across video screens in a darkened control room. The squid's squirt at a camera-toting robot submarine is one of many surprising moments for the 30-member scientific team off the Oregon coast. They are the first to view the floor and walls of a submerged geologic feature called the Astoria Canyon.

Beginning 10 miles from the Columbia River's mouth, the underwater gash winds about 70 miles westward and reaches a depth of 7,200 feet -- more than 1,000 feet deeper than the Grand Canyon. The sea floor canyon was carved during the past 1.8 million years as sediment-laden currents flowed downhill through the area. The massive Missoula Floods swept through the Columbia River Gorge dozens of times about 15,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age. At the time, sea level was hundreds of feet lower than it is now, and the Columbia River dumped its sediment-filled contents directly into the underwater canyon, cutting the abyss even deeper.

Astoria Canyon has drawn marine scientists from varied fields who are examining the chasm's geology, biology and chemistry. The interdisciplinary research team is examining the canyon's processes, its landslides, faults and currents, the inhabitants of its sediment-covered bottom and steep walls, and the fish, krill and other creatures that dwell in its waters. The scientists are participating in a new national Ocean Exploration program led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The effort is aimed not only at gaining scientific knowledge but also at generating public interest in ocean research.

Lewis and Clark Legacy

The $750,000 expedition off Oregon's shores, known as the Lewis and Clark Legacy, is among the program's first research efforts. The Ocean Exploration program allows scientists to focus more on exploration than on specific scientific questions or hypotheses. "We thought it would be interesting to examine this canyon because it had never been seriously looked at with any modern tools," said Robert W. Embley, a marine geologist with NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Newport. "It also seemed fitting with the 200th anniversary of the Lewis and Clark expedition. . . . So it combined both scientific and historical ingredients." Embley is co-chief scientist on the canyon cruise with W. Waldo Wakefield, an oceanographer with the Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Newport, which is part of NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service.

Dr. Robert Embley, marine geologist, geophysicist, and co-chief scientist of the Lewis and Clark Legacy Expedition.

Dr. Waldo Wakefield, fisheries ecologist and co-chief scientist of the Lewis and Clark Legacy Expedition.

Wakefield said he had often wanted a chance to explore while working on research projects. "It's frustrating when you see something interesting that might be outside of the realm of the study you're working on but don't have an opportunity to investigate it," he said. "This program gives us a chance to look around, but to do so in a rigorous scientific context rather than just exploring for exploring's sake." The squid is only one of numerous animals that Embley, Wakefield and their colleagues spot as the remote-controlled submersible glides along the seafloor. Offshore canyons are noted for their biodiversity, and the Astoria Canyon is no exception.

Cast of Thousands

Thousands of sea cucumbers and red sea stars dominate the thick sediment in some areas, but the list of creatures grows with each dive: tiny worms, Dover and rex sole, sablefish, lantern fish, hake, halibut, rattails, shrimp, skates, anemone, sponges, jellyfish, hagfish, poachers, sculpins, crabs, clams, grenadier and snakelike fish called eelpouts. An assortment of thornyheads and other rockfish with equally colorful names are spotted throughout the canyon: rosethorn, sharpchin, greenstripe, yellowtail, canary, shortspine, splitnose and widow.

Aggregations of sea cucumbers and sea stars on the soft, muddy bottom of Astoria Canyon. Click image for larger view.

A submarine landslide exposed this mudstone scar devoid of marine life and sediment, indicating recent mass-wasting activity. Click image for larger view.

Landslides also get a close examination from expedition scientists. Some of the slides may have been generated by earthquakes; others seem to have been a result of the fragile soft rocks of mudstone that make up many of the steep slopes. Embley and Wakefield are excited about having marine scientists aboard who are experts in a variety of research fields. They say it provides an opportunity for specialists to learn from each other and share ideas as they examine an entire ecosystem.

Brian N. Tissot, a marine ecologist at Washington State University in Vancouver, Wash., is looking at invertebrates and their habitat. Jacqueline M. Popp-Noskov, a bioacoustician at Oregon State University, is using a high-frequency acoustics instrument that is towed in the water to search for aggregations of fish and zooplankton. Edward T. Baker, an oceanographer with NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, deploys 1,000-foot-long sensor-loaded lines that rise from the canyon floor to measure the currents. The moorings will be recovered during a cruise next month.O

ther scientists are from the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the Southwest Fisheries Science Center in Santa Cruz, California, and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Jeff Goodrich, an earth sciences teacher at Lake Oswego High School, is on the cruise to help log data. The research team will issue a report on its findings later this year.

Dan Parker, captain of the fishing boat Sea Eagle out of Warrenton, is participating in the research by collecting samples that will help scientists interpret the data collected by the bioacoustics instrument. He's been fishing these waters for nearly 30 years and is getting his first look at the canyon floor via a monitor linked to the submersible, which is 1,500 feet deep. "This is very interesting," Parker said, looking at the screen. "I want to help out because the more we know, the better it is for all of us. This is a very productive area, and we want to keep it that way."

NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown. Click image for larger view.

The remotely operated vehicle ROPOS, in its cage, during an equipment check before the NOAA ship Ron Brown reached Astoria Canyon. The ROV conducted seven dives into the canyon. Click image for larger view.

No Time Wasted

The scientists all put in long hours, working in shifts to collect data around the clock. Research time at sea is precious, and they take advantage of every available minute. They're aboard the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown, a 274-foot-long research vessel, the largest, newest and most sophisticated in the agency's 15-ship fleet. The ship, based in Charleston, S.C., already has been involved in important research efforts in the Pacific this year, including projects that examined pollutants from Asia and the role the ocean plays in storing and releasing carbon. The eight-day cruise, which took about six months to plan, began in Victoria, British Columbia, on June 26 and ended in Astoria on July 3. The researchers concentrated on about a 25-mile section of the eastern part of the canyon. This week, the ship and many of the same researchers are ending a final phase of the expedition by looking at Heceta Bank, a rocky shoal off the central Oregon coast that is an important fishing area.

To prepare for the Astoria Canyon cruise, Embley and marine geologist Chris Goldfinger of Oregon State University used two sonar technologies -- a high-resolution multibeam system and a deep-towed sidescan system -- on board a smaller vessel to map the canyon.

Remote Operations

The first detailed map of the canyon provides researchers the information they need to decide which areas of the canyon to explore. Although the scientists use an assortment of instruments to explore the canyon, most of the attention is focused on the remotely operated vehicle called ROPOS, an acronym for Remotely Operated Platform for Ocean Science.

The Canadian vehicle, which can dive to 16,500 feet, is spending nearly 75 hours on seven dives to examine different areas of the canyon. Once in the water, the robot is released from a large protective cage and roams the floor. The ship transmits commands down an electrical-optical cable to the vehicle, while ROPOS sends video images and data up to the scientists and the submersible's pilots. A robotic manipulator arm on the vehicle places instruments and collects samples on the sea floor. Sample containers bring delicate organisms and rocks to the surface.

An eight-member crew maintains and operates ROPOS, which made its 600th dive during the cruise. Its most famous was in 1998, when it was used to raise four "black smoker" chimneys from hydrothermal vents 180 miles off the Washington coast. The submersible also is being used to explore Heceta Bank and will participate in an upcoming cruise over Axial Volcano off the Oregon coast.

Even with ROPOS, the expedition was able to explore less than 1 percent of the Astoria Canyon in the one-week cruise. But the scientists were pleased with their work as the ship pulled into Astoria. "In a short seven days we were able to see a representative sample of the biological communities and the geological features of the canyon," Wakefield said. "It's such a significant feature, and I'm glad we had an opportunity to investigate it. We hope it will lead to further explorations here." Embley agreed. "This was a prototype exploring expedition, so we learned a great deal about how to balance the differing needs of the scientists to get a good idea about the relationship of the geology and biology in this unique ecosystem," he said. "We'd always like to have more time to explore, but this was an excellent start."

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.