by Jonathan Parshall, Co-author of Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway

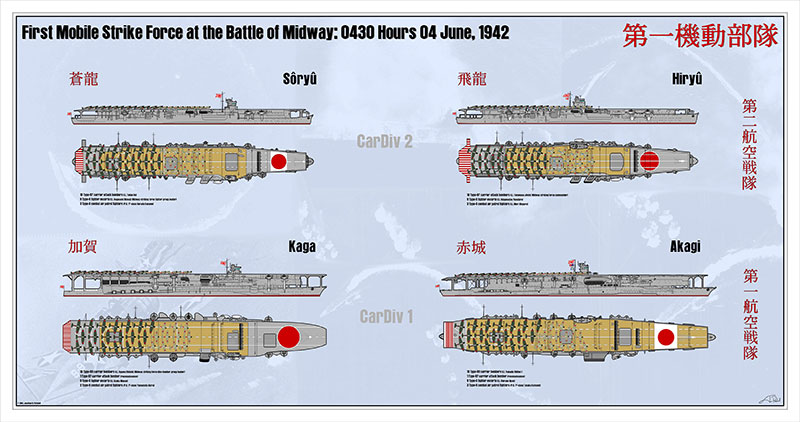

Author's depiction of Japanese carrier force just prior to launching an initial attack on the island of Midway, June 4, 1942. Image courtesy of Jonathan Parshall. Download larger version (4.8 MB).

The Battle of Midway was the single most important naval engagement of World War II. Occurring just six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the resounding American victory at Midway checked what had been an almost unbroken string of Japanese victories during the opening phase of the Pacific War.

During a battle that stretched from June 4-7, 1942, the Japanese lost their four finest aircraft carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū and Sōryū—along with nearly 250 aircraft and over 3,000 sailors killed. In return, the Americans lost the carrier Yorktown, and around 300 men.

This victory restored the balance of carrier power in the Pacific at a crucial time in the war and allowed the Americans to begin considering counter-offensive activities of their own. Just two months later, they would land troops on Guadalcanal, which initiated what was to become the decisive campaign of the entire war. Thus, Midway marks the high tide of the Japanese offensive.

Interest in the battle has not waned in the intervening 74 years since it was fought. And one of the great mysteries of this battlefield remains where, exactly, are the resting places of the four Japanese carriers lost there?

In 1998, Dr. Robert Ballard located and documented the wreck of the Yorktown. However, though he attempted to locate the Japanese carriers, he was unsuccessful in his efforts.

Just a year later, the Nauticos Corporation employed an innovative new search technique called re-navigation to look for Kaga. By utilizing the log of the U.S. submarine Nautilus (which had attacked the Kaga after she had been set afire by American divebombers), Nauticos was able to deduce a more probable resting place for the vessel.

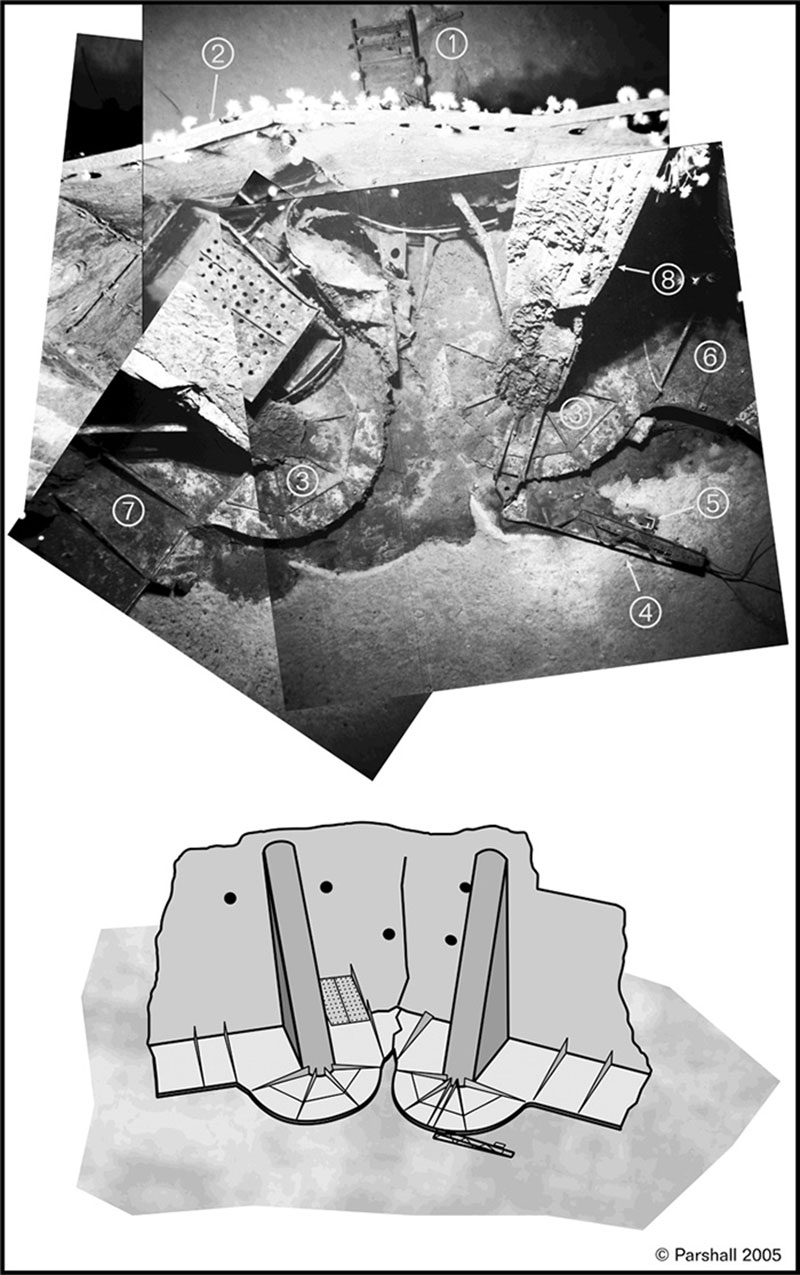

Photo collage of The Chunk showing: 1. Ladder. 2. Exterior bulkhead. 3. 25mm AA gun tub (inverted). 4. Landing light array (assists pilots in lining up their approach). 5. Landing light. 6. Walkway aft. 7. Walkway forward. 8. Strut support for gun tub. Image courtesy of Nauticos and Jonathan Parshall.

Nauticos' technique paid results. Though the main wreck of Kaga was not found, a large piece of wreckage (referred to as “The Chunk” by Nauticos) was located and positively identified as having been an inverted section of Kaga’s starboard aft anti-aircraft gun mounts. About the size of a house, it lies on the bottom, some 17,000 feet down in the chilly Pacific.

Finding “The Chunk” was a big step forward, proving the validity of Nauticos’ re-navigation approach. The mystery then became, where is the main wreck of the carrier? At first glance, it would seem that finding the 812-foot long hull of Kaga wouldn’t be all that difficult. However, the ocean is a big place and the waters are incredibly deep at over 5,000 meters. So deep, in fact, that the resolution of sonar, a tool mounted on the bottom of a ship used to map the seafloor and find shipwrecks, is very coarse, making it nearly impossible to detect a shipwreck the size of Kaga. Finally, the bottom bathymetry of the area is not well understood, making it difficult to distinguish a potential hull from a simple geographic feature like a seamount.

The further challenge is that Kaga’s damage isn’t perfectly understood, except that she was the most badly bombed of the Japanese carriers that day. She was attacked at 10:25 on the morning of June 4, 1942, by aircraft from the carrier USS Enterprise, and suffered such terrible initial damage that the Japanese literally lost count of how many times she was struck. She suffered at least five (and likely more) major bomb hits, and probably several minor hits.

Japanese accounts strongly indicate that Kaga suffered a powerful fuel-air explosion just minutes after the initial attack, and that large pieces of debris were blown off the ship. But was ”The Chunk” part of this initial explosion? It’s unknowable. Despite her initial damage, almost incredibly, Kaga maintained power and remained underway at low speed for the next two and a half hours. Ablaze from stem to stern, she vainly tried crawling away roughly to the north, out of the battlefield.

All during this time, the American submarine Nautilus was trailing the doomed carrier, attempting to close the range so as to attack with torpedoes. But the Nautilus was unable to get any closer, meaning Kaga was moving away about as fast as Nautilus could manage submerged.

At about 1:00 in the afternoon, Kaga finally ground to a halt. It is believed that her trapped engine room crews (212 men in all) had by now expired at their posts. This allowed Nautilus to finally set up an attack in the early afternoon. However, Nautilus’s fish – or torpedoes – proved to be defective and no further damage was caused (as was so often the case with American torpedoes early in the war). Nautilus was depth-charged for her trouble, and driven away.

Kaga was eventually scuttled later that evening by Japanese destroyers. The net result was that ”The Chunk” could have come off either at the time she was bombed, or at any point during Kaga’s agonizing retreat from the battlefield. This means that Kaga’s main wreck could be anywhere along her trail.

That said, the main wreck is believed to be relatively close to “The Chunk.” Kaga’s speed was so slow (between 2-4 knots) during her two and a half hour egress that it stands to reason that her hull probably lies within single-digit miles of the location of “The Chunk” itself. Even accounting for factors such as drift, her wreck must be nearby. The challenge is to better understand the bottom bathymetry and to generate a sonar survey that will build upon the results of the earlier 1999 Nauticos expedition. This is where NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer comes in.

Hopefully, with NOAA’s help, Okeanos Explorer will be able to better clarify the bottom bathymetry, as well as identifying potential areas of interest for follow-on expeditions. And if a favorable target is identified, we have a world-class remotely operated vehicle to put down on it.

Who knows, with a little bit of luck, Kaga may be out there waiting for us! She’s got to be around here somewhere!

Jonathan Parshall is co-author, with Anthony Tully, of Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. He and Mr. Tully will both be participating in relevant Hohonu Moana: Exploring Deep Waters off Hawaii expedition dives as historical consultants.