by Chris Ritter, Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration

November 18, 2019

Imaged by its camera sled ROV Seirios, ROV Deep Discoverer explores some interesting, yet potentially dangerous, geology on the Pourtalès Terrace during Dive 10 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 304 KB).

Whenever NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer plans to explore off the southeast coast of the United States, we know there will be challenges. No matter how much we anticipate and plan for them, it’s always disappointing when we’re unable to deploy the remotely operated vehicles (ROV) and share the wonders of the deep with scientists and other dedicated followers who join us live online. The 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration cruise has certainly had its fair share of challenges and lost dive days. Here’s a little insight into the factors that have been guiding our dive/no dive decisions.

Potentially dangerous situations are inherent in ROV operations during launch and recovery and while operating at depth. During launch and recovery, deck crew and ROV engineers are on the back deck of the ship assisting with operations. In rough weather (i.e., wind over ~25 knots or 29 miles per hour and waves over ~6 feet), the ship motions could become so extreme that the deck crew could lose footing on deck, or the ROVs could swing unsafely while being lifted by the crane. It’s part of the dive supervisor’s job to help minimize the operational risks for personnel on deck.

The dangers of operations are not limited to launch and recovery. While descending and ascending in the water column, the cable that attaches the ROVs to the ship can become entangled in the ship’s propellers or rudders if the ship is not making proper forward way through the water. On the seafloor, there are concerns that the currents could push the vehicles into geological features. The dive supervisor helps manage ship speed and movements so that both the ROVs and ship are not harmed during operations.

There is no formula that we can use to decide whether or not it’s safe to dive. When preparing for a deepwater ROV dive, the navigator, dive supervisor, and ship operators study the three major forces acting on the ship. These major forces are the wind, the seas (i.e., the waves), and the currents.

At most dive locations around the world, the wind and seas are the predominant forces. If these two forces are minimal, the dive supervisor and commanding officer usually give the “green light” for a dive. This is not the case in the waters of the Atlantic off the Southeastern U.S. because of the Gulf Stream, which is a strong ocean current that brings warm water from the Gulf of Mexico into the Atlantic Ocean and extends along the eastern coast of the United States and Canada.

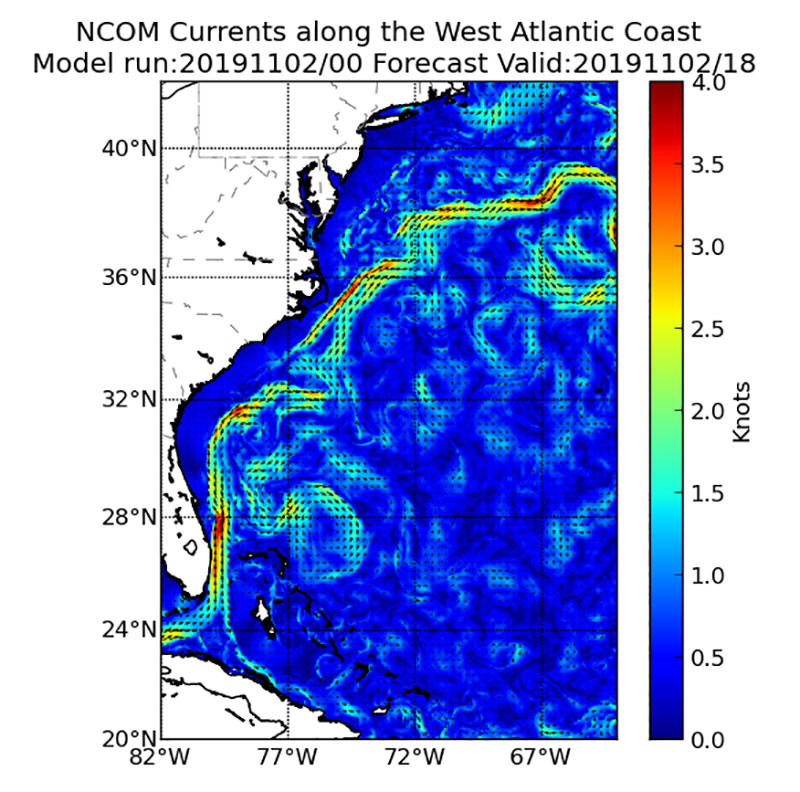

The Gulf Stream direction and magnitude is modeled by the U.S. Navy Coastal Ocean Model (NCOM), which is a high-resolution model that offers ocean current data at a 2 nautical mile (2.3 mile) resolution every 24 hours. The navigator, dive supervisor, and ship operators use this model output to very roughly estimate expected currents at each dive site. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Prediction Center. Download larger version (jpg, 344 KB).

For almost all the ROV dives during the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration, the Gulf Stream has been the predominant force on the ship. Surface currents such as the Gulf Stream affect the ship’s ability to hold position during a dive and affect how the vehicles stream behind the ship during launch and recovery when the vehicles are in the water column. Since the Gulf Stream is such a large, consistent, and high-magnitude force, there are also subsurface currents that affect the ROVs during their descent, ascent, and throughout the dive while on bottom.

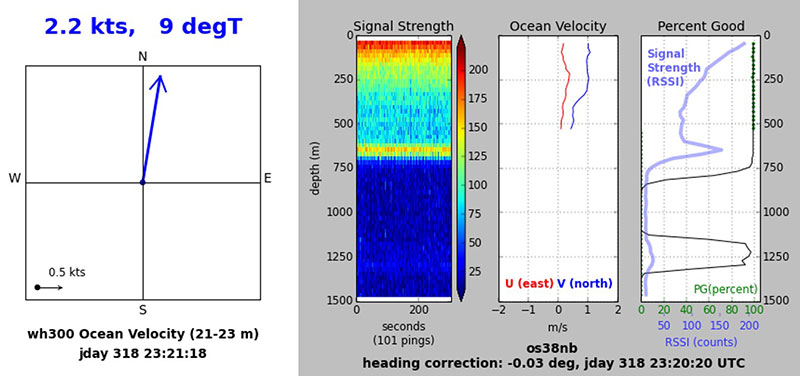

The ROV team on the Okeanos Explorer uses an acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) to estimate surface and subsurface currents. The figures below show readings from the ADCP taken at a dive site that was deemed unsafe for dive operations on the day we were there. The figure on the left displays the surface current direction and magnitude and the figure on the right displays the subsurface current profile throughout the water column. Although the 2.2 knots (2.5 miles per hour) of surface current are much higher than seen at a typical dive site, this alone did not lead to the decision to cancel the dive. With a bottom depth of about 500 meters (1,640 feet), the subsurface current profile shows about a 0.5 meter/second (~ 1 knot, or 1.7 miles per hour) current close to the bottom. This situation isn’t safe for the ROVs, and thus we made the difficult decision to cancel the dive.

The conditions on November 14, 2019, were unfavorable for diving. The readings on that day from the acoustic Doppler current profiler show the surface current direction and magnitude (left) and the subsurface current profile throughout the water column (right). Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Marine and Aviation Operations. Download larger version (jpg, 277 KB).

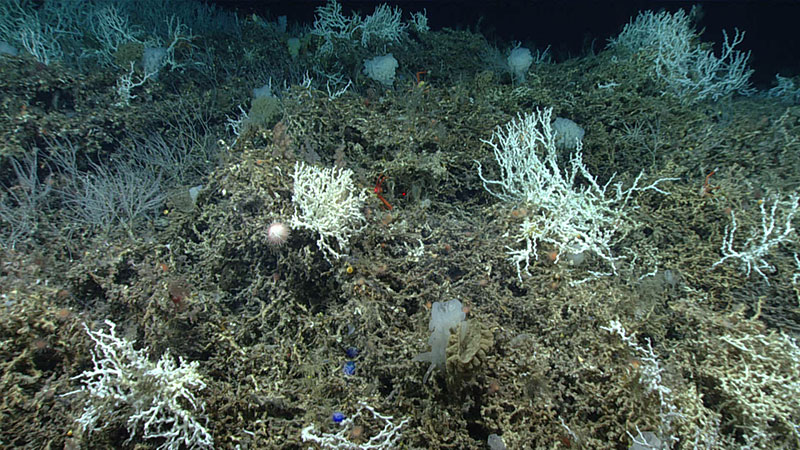

The Gulf Stream isn’t all bad though! It’s a big reason why these dive sites are so valuable to the scientific community (and so interesting for those who follow the dives online). The warm Gulf Stream currents bring nutrients and help sustain life like that found among the deep, dense, and diverse coral communities that we’ve been documenting throughout this expedition. With some of the imagery, samples, and data that have been collected at these dive sites, it’s easy to see why diving near the Gulf Stream can be worth its challenges.

Marine life was both abundant and diverse on the Central Blake Plateau, an area through which the Gulf Stream passes, during Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).