Date: November 6, 2019

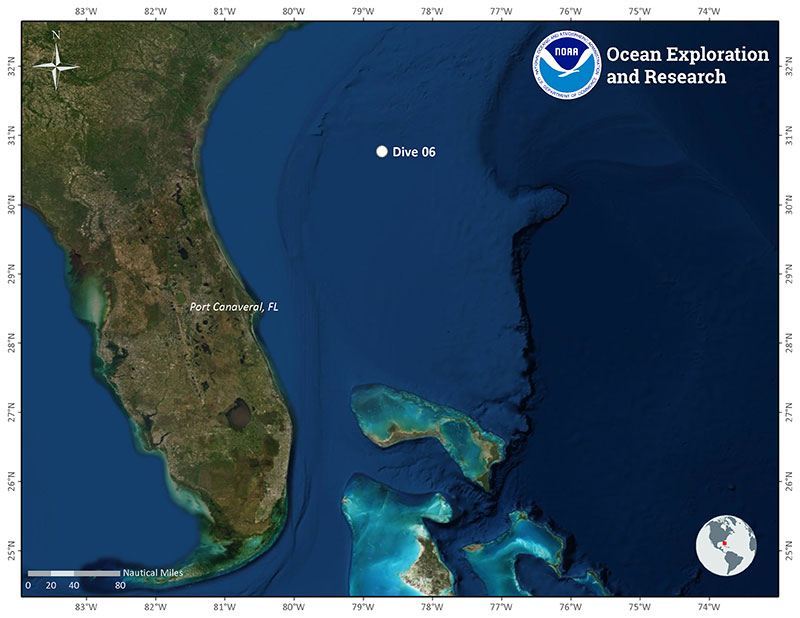

Location: Lat: 30.7599°, Long: -78.74255°

Dive Depth Range: 766 - 842 meters (2,513 - 2,762 feet)

Access Dive Summary and ROV Data

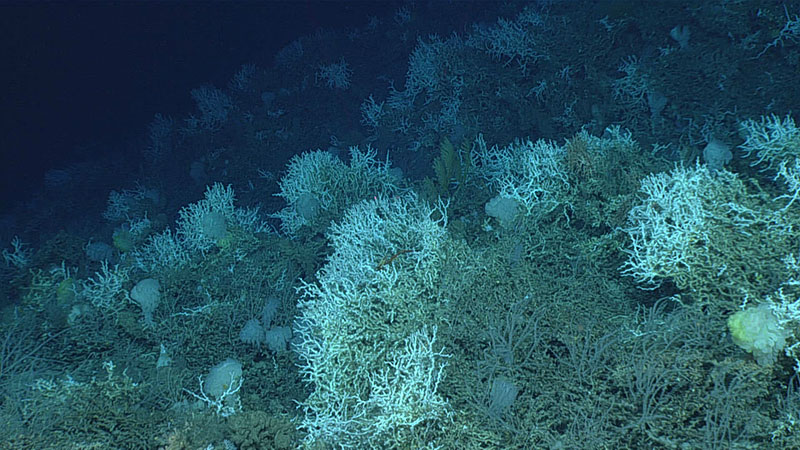

Deep-sea coral reefs like this one seen on Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration are created by stony corals, Lophelia pertusa, in this case, that form large geological structures over thousands of years. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 546 KB).

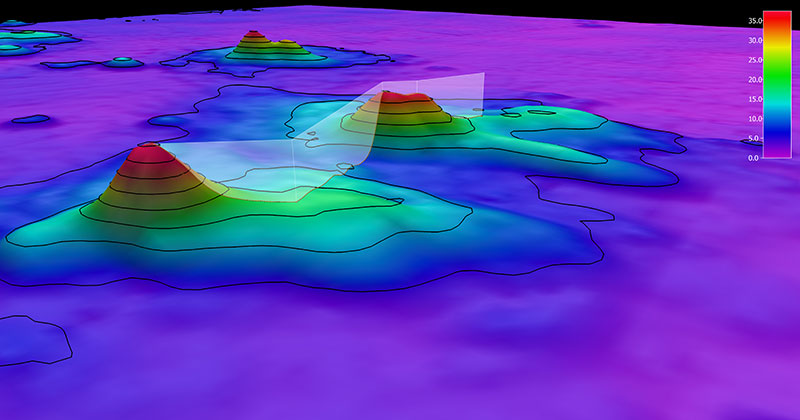

To quote our expedition coordinator, today’s dive was “phenomenal.” Mapping data collected during the first part of this expedition showed some interesting seafloor features that we couldn’t wait to explore (since mound features are known hotspots of biodiversity on the Blake Plateau). On this historic dive, we encountered two live Lophelia reefs that no one knew were here, until now.

The plan for the day was to target two large mounds about 160 miles off the coast and outside the Stetson-Miami Terrace Habitat Area of Particular Concern, unlike the previous dives. By diving both inside and outside the protected area, we are hoping to learn about the connectivity of the deepwater communities at these sites.

We saw this large demosponge during the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Like other sponges, it’s a filter feeder and does best in areas where the currents can provide it with the food (particulate organic matter) it needs to survive. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

This bird squid (Ornithoteuthis antillarum) is holding its tentacles close to its body, a likely defensive posture assumed in response to our presence in its deep-sea home during Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 782 KB).

After landing at the base of the southern mound, we headed north. The seafloor on this first mound consisted of coarse skeletal sands and coral rubble with a dark crust (either phosphoritic or ferromanganese). Wildlife was sparse as we began the dive, but it increased, along with standing dead coral frameworks, as we ascended the mound. Early observations included glass fan sponges, brittle stars, hydroids, small white sparsely branched octocorals, five-armed feather stars, and pancake sea urchins.

Before we reached the top of the mound, we also saw an increasingly diverse sponge garden with an octopus, octocorals, a variety of sea stars, solitary cup corals, a bird squid and jellyfish in the water column, and, remarkably, a sea spider with babies.

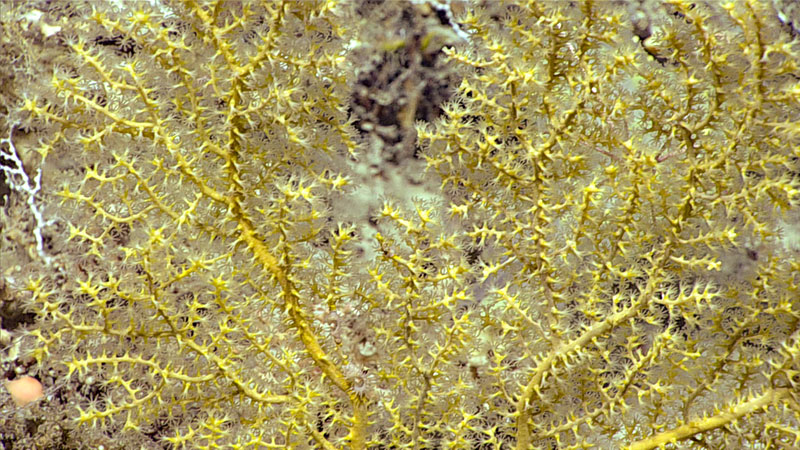

During Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration, we encountered a number of gorgonians, including this yellow sea fan. Gorgonians are soft corals, which means they are not reef-building corals. They can be distinguished from hard corals by the number of tentacles per polyp. Hard corals have six, soft corals have eight. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

On the top of the first mound, we found a healthy living Lophelia reef with abundant 3-4 meter-wide coral heads. Coverage was about 50 percent live coral and 50 percent standing dead coral. Among the corals, we encountered quite a lot of diversity: glass sponges, cupcorals, squat lobsters, a few black corals, and more. While there was less living coral on the northern side of the mound, there was still a lot of sporadic Lophelia thickets.

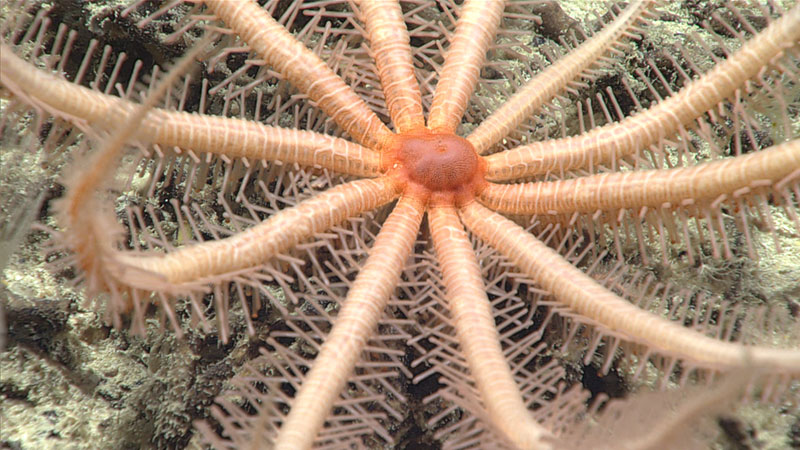

As we began to travel up the second mound, the seafloor was mostly coral rubble with some standing dead coral. We saw sponges, corals, sea lilies with hydroids on their stalks, brittle stars, a blackbelly rosefish, a 12-armed pink sea star, and a yellow mesh fan, which we collected and may represent a new species of bryzoan.

Initially mistaken for a sea feather, this pink 12-armed animal is actually a brisingid sea star. The spines on its arms are covered with small, claw-like structures that it uses to catch small crustaceans as they swim by in the current. It then uses its tube feet to move its prey down to its mouth (at its center). Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Farther along, we encountered thickets of stony coral and an increase in density of standing dead coral frameworks. On the southwest side, the amount of living Lophelia increased along with other types of marine life. Here we sighted a knotted sea urchin and chimney sponges.

As we neared the northern side of the mound, the coral abundance and overall diversity decreased. While we considered returning to a more productive area, we chose to continue on and were rewarded at the mound’s second summit with an increase in living Lophelia with 3-5 meter-wide coral thickets as well as glass sponge abundance.

In addition to the yellow mesh fan, we also sampled some sediment and collected a glass sponge (Aphrocallistes beatrix) and a piece of living Lophelia pertusa, both for the Atlantic Seafloor Partnership for Integrated Research and Exploration (ASPIRE).

It’s not unusual to come across new species when we explore deep-sea areas that no one has ever been to before. Our scientists were unable to identify this yellow mesh fan (bryozoan) seen on the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration, so we collected it so we can learn more about it. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

The high diversity of the Lophelia reefs seen for the first time during Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration is evident in this image, which features a variety of Lophelia inhabitants, including glass sponges, squat lobsters, a snail, an urchin, and more. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

During Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration, we observed this male sea spider, pycnogonid, carrying babies. Much like sea horses, the female produces eggs, but once the eggs are fertilized, the male carries them using specialized legs called ovigers. If you watch the video closely, you can see a baby sea spider float away, out into the world. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download larger version (mp4, 59.3 MB).

Location of Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration expedition on November 6, 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

The remotely operated vehicle track for Dive 06 of the 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration expedition, shown as an orange line with a white curtain. This mapping data was collected during the first part of the expedition. Legend shows water depth in meters. Download larger version (jpg, 3.7 MB).