February 23, 2017

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Geology Science Team Lead, Dr. Matthew Jackson, retrieves one of the rocks collected during the dive from the rock box on remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 796 KB).

If you’ve tuned in to the live video from NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, chances are you’ve seen remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer (D2) collect geological and biological samples from the seafloor. Ever wonder what happens to those samples after they are collected?

Once a sample is brought onboard the ship, the onboard science leads – for this expedition, that’s Santiago and Matt – carefully photograph and document the specimen and provide a tentative field identification. The animals are then preserved using formalin or ethanol, depending on which preservative is more desirable for the type of animal. For coral and sponge specimens, a portion of each sample is preserved for taxonomic analysis to determine biologic classification such as species and genus; genetic analysis; and in some cases, histological, or tissue, examination. Once prepared, samples are stored until they can complete the next leg of their journey.

Biology Science Team Lead, Dr. Santiago Herrera, transfers a coral sample from the insulated bio boxes on Deep Discoverer to a bucket full of chilled water for transfer to the wetlab. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Once in the wetlab, the coral is photographed and given a preliminary identification. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 10.3 MB).

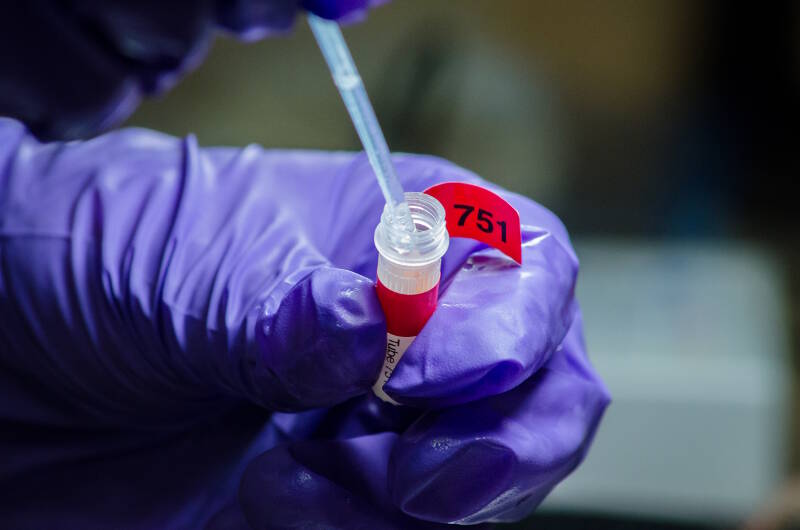

A small piece of coral is clipped and placed in a vial with a preservative for later genomic analysis. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 10.3 MB).

The rest of the sample is preserved by being placed in a jar or bag and covered with 95 percent alcohol to prevent further degradation. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 10.4 MB).

After an expedition ends, the samples are transferred to the lab of CAPSTONE Science Advisor Dr. Christopher Kelley at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Here, Chris and his team catalogue the samples and prepare them for archival. Samples are then shipped to the appropriate repository with preliminary identification provided in addition to photographs and a deed of gift, donating the specimens to that repository to make them accessible by others.

Specimens are made available through several repositories. Biological samples are made available through the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History Research and Collections . Here, they will be taxonomically identified, curated, and made accessible through the Invertebrate Zoology Collection . For selected coral and sponge samples, a portion of the sample may also be sent to the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, and additional small tissue samples may be collected for later genetic analysis at Northeastern University’s Ocean Genome Legacy Center (OGL). The results of the genetic analysis by OGL are made publicly accessible.

All geological samples are sent to the Oregon State University Marine Geology Repository, where they will be described and made publicly accessible.

Like all data collected on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, samples are made publicly available as soon as possible. Once samples have been described and curated at their respective repositories, anyone with appropriate credentials can request access to the samples by contacting the repository directly.

While D2’s amazing imaging capabilities allow us to see great detail and observe life in situ, there are some things that we can only learn from a physical specimen. For example, only from a physical sample of a rock can geologists definitively determine the composition of the rock and conduct chemical analyses that reveal details about the rock’s age and origin. On this expedition, analysis of rock samples could lead to insights into the formation of Samoan seamounts, providing information about plate tectonic activity in the region.

When it comes to biological samples, seeing a live organism gives us information about the animal’s color, its behavior, and habitat that are lost when an animal is brought to the surface. However, it is only with a physical sample that scientists can make species-level identifications or conduct genetic analyses to determine connections between animals in different locations.

The sampling philosophy on the Okeanos is to take just enough for scientists to be able to characterize a dive site. Samples are only collected if they can provide a general representation of the biological and geological settings for a given dive or an area of interest. This, combined with the limited onboard processing and storage capabilities of the Okeanos, means that typically there will be no more than four to six samples taken during any given dive.