by Scott C. France, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

September 5, 2019

You usually don’t have to listen to very much of an Okeanos Explorer dive before you hear one of the scientists refer to “sclerites” when looking closely at an octocoral. What are these structures? Sclerites are part of the microskeleton of an octocoral that provides support and protection. Because they are so varied in shape, size, and abundance in the tissue, they are used by taxonomists—specialists in the description, naming, and identification of species—to help sort out the diversity of octocoral species.

Sclerites are small aggregates of calcium carbonate (in its calcitic mineral form) embedded in the soft tissue of octocorals. They range in size from the tiny 0.02 millimeter long ovoid sclerites of the soft coral Xenia to the “giant” 5 millimeter paver stone-like sclerites of Paracis. Sclerites are formed in special cells in the octocoral that secrete a protein matrix around which the calcite crystals are deposited.

Needle-like sclerites protrude between tentacles to form a formidable-looking ring around the red-colored mouths of bamboo coral polyps. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 792 KB).

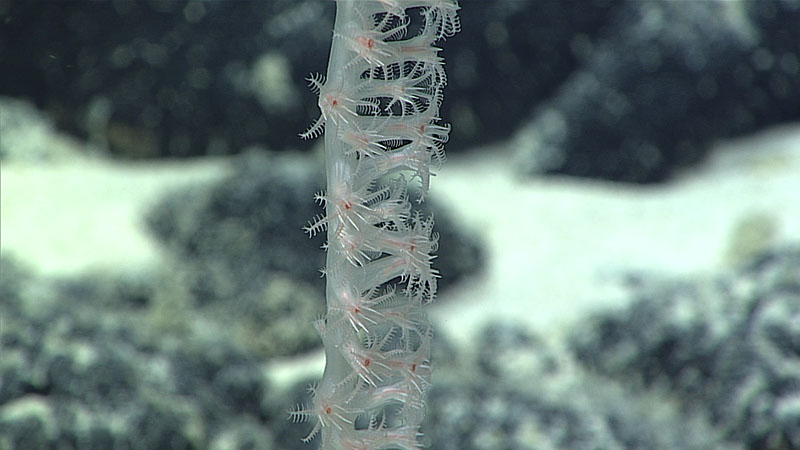

Rod-like sclerites are aligned in tracks running up the polyp body wall in a bamboo coral. Even smaller scale-shaped sclerites are packed into the tissue giving it an opaque appearance. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 978 KB).

One of the reasons you hear sclerites referred to so frequently on our streaming video is that their shape and arrangement are used to help identify species. Indeed, it is the complement and distribution of sclerites across the colony that taxonomists used in the first place to distinguish and describe different species (along with other key characteristics such as mode of branching, type of skeleton, and polyp size).

A fragment of a Primnoidae colony (genus Narella) under a microscope showing three pairs of polyps. The polyps, curled downward against the main axis, are encased in plate-like sclerites. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1 MB).

For example, among the bamboo corals (or at least the common deep-sea subfamily Keratoisidinae), most sclerites are modifications of a rod- to needle-like form, some with more curvature than others; their density and specific positioning in the polyp body wall may be diagnostic among species and genera. In the primnoid octocorals, sclerites take on a myriad of variations of a flattened scale, many elaborated with flanges, spines, warts, or ruffles. A primnoid polyp is a marvel to see under a microscope, as they are sheathed in these sclerites like a medieval knight in armor. Acanthogorgia octocorals have warty spindle sclerites arranged in “en chevron” rows, like the stripes of a sergeant’s insignia, often culminating in a crown of thorn arrangement of spines around the tentacles. In the Scleraxonia group of octocorals, which includes the bubblegum corals (Paragorgia) and precious corals (Corallium) among others, sclerites are fused in a consolidated axis that forms the main skeleton of the colony in contrast to the protein-based skeleton of the gorgonian seafans.

Spiny sclerites on an Acanthogorgia octocoral give the polyps a pin cushion-like appearance. The coiled pink spiny arms belong to ophiuroid brittle stars that live on the coral. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Discovering the Deep: Exploring Remote Pacific MPAs. Download larger version (jpg, 937 KB).

Clavularia, here seen during dive 6 of Deep Connections 2019, is a stoloniferous octocoral that grows in ribbons and mats over rock or skeletons of coral or sponges. The purple color is due to a pigment in the soft tissue and the white is reflections from sclerites. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep Connections 2019. Download larger version (jpg, 496 KB).

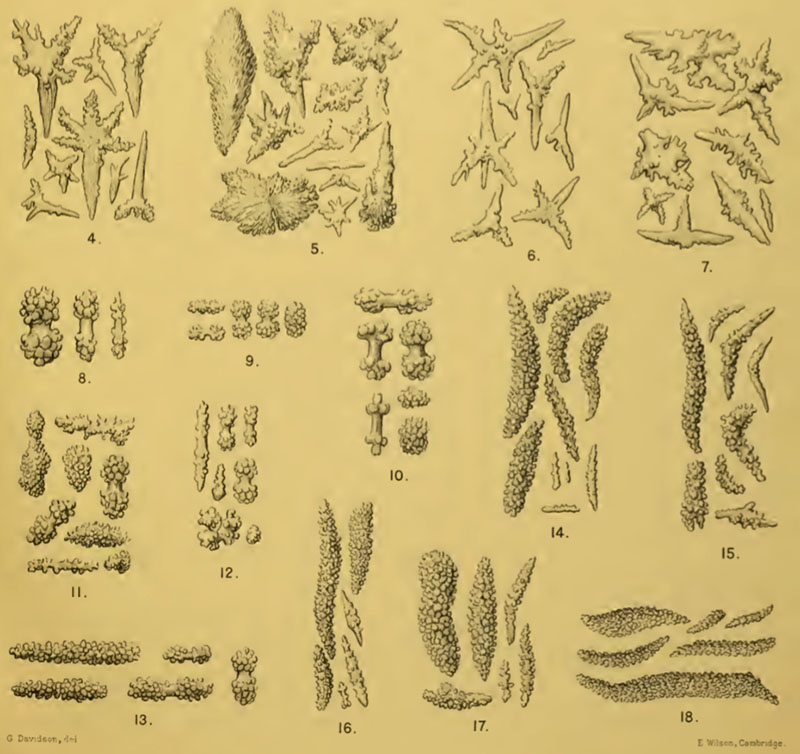

Octocoral taxonomists have come up with fanciful, descriptive names for sclerites that are evocative of their shape, such as thornstar and thornspindle, antler, balloon club, finger biscuit, hockey stick, butterfly, caterpillar, and wart club. Even at the microscopic scale, octocorals show incredible diversity and beauty, adding to their aesthetic beauty.

A figure from a taxonomic monograph published in 1909 shows hand drawings of sclerite variation among 15 species of octocorals from the Indian Ocean. Identification of most octocoral species comes down to this level of microscopic detail. Image courtesy of Thomson JA, Simpson JJ (1909), An Account of the Alcyonarians Collected by the Royal Indian Marine Survey Ship Investigator in the Indian Ocean. 1–316 and Plates I-IX. Download larger version (jpg, 477 KB).