by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service - National Wildlife Refuge System - Northeast Region

NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service - Greater Atlantic Region

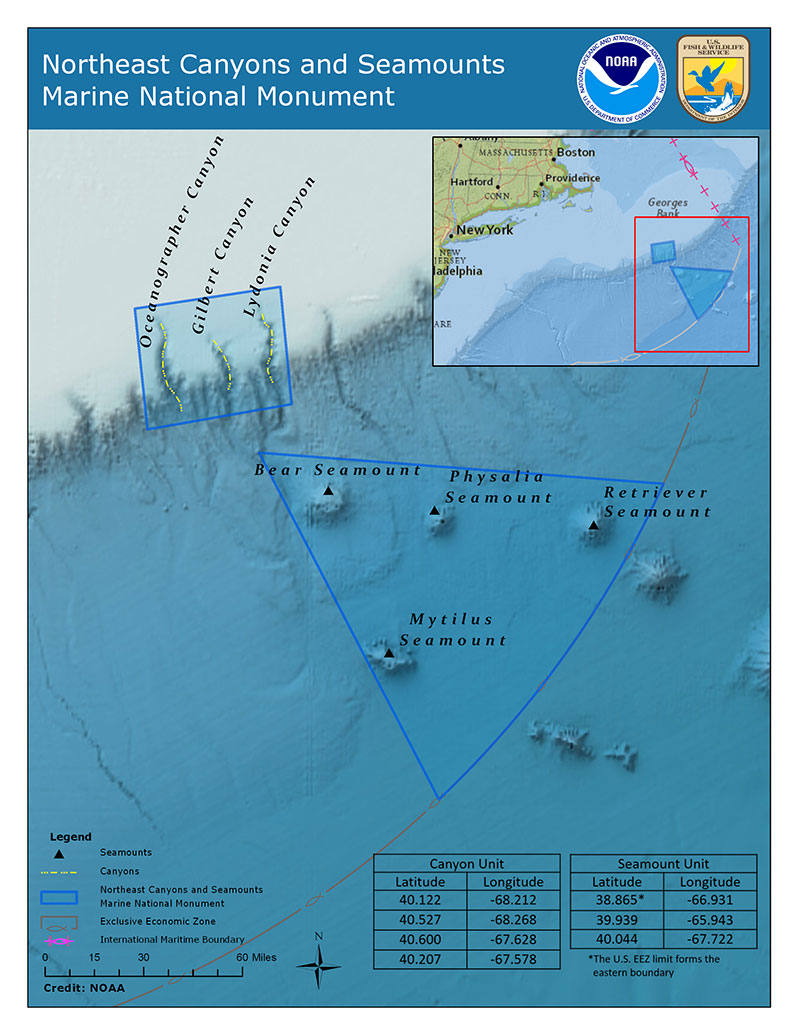

This map of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument shows some of the submarine canyons that cut into the deep seafloor of the continental margin of the eastern United States and the seamounts offshore. The habitat characteristic of these geological features is discontinuous, with communities isolated by the sediment-covered slopes between them. Image courtesy of USFWS/NOAA. Download image (jpg, 2.0 MB).

On September 15, 2016, President Barack Obama established the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument by Presidential Proclamation 9496 (81 FR 65159), under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906. The Monument is located about 130 miles off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and is approximately the size of Connecticut (4,913 square miles). It is the first and only marine national Monument in the Atlantic Ocean. The Monument protects fragile and largely pristine deep-sea environments alive with marine animals. Protecting this unique area as a national Monument will safeguard it for future generations.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), in the Department of Interior, and NOAA, in the Department of Commerce, jointly manage the Monument. The Monument includes the waters and submerged lands within two Units – a Submarine Canyons Unit and a Seamounts Unit.

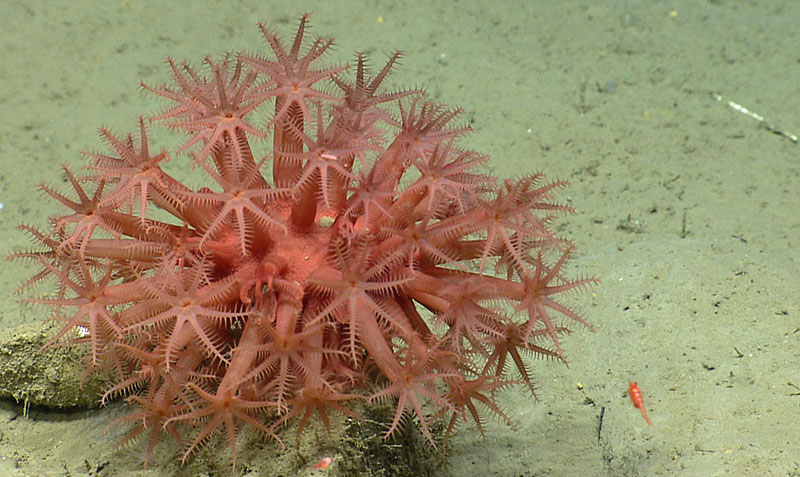

Anthomastus coral in Oceanographer Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 1.4 MB).

There are three undersea canyons within the Monument: Oceanographer, Gilbert, and Lydonia canyons. These canyons are among the largest of about 35 major undersea canyons that line along the U.S. continental shelf edge from Cape Hatteras north to the Canadian boundary. From the lip of Oceanographer Canyon to its deepest location, the canyon is approximately 1,220 meters (4,000 feet) deep—this is the average depth of the Grand Canyon!

These canyons are cut into the continental slope and lower continental shelf. They have steep walls and are largely formed by erosion on the continental slope.

Upwellings of deep, cold water around the canyons bring nutrients to support large quantities of plankton, krill, forage fish, and schools of squid, which in turn, nurture high abundances of large marine animals such as whales, dolphins, and large migratory fish.

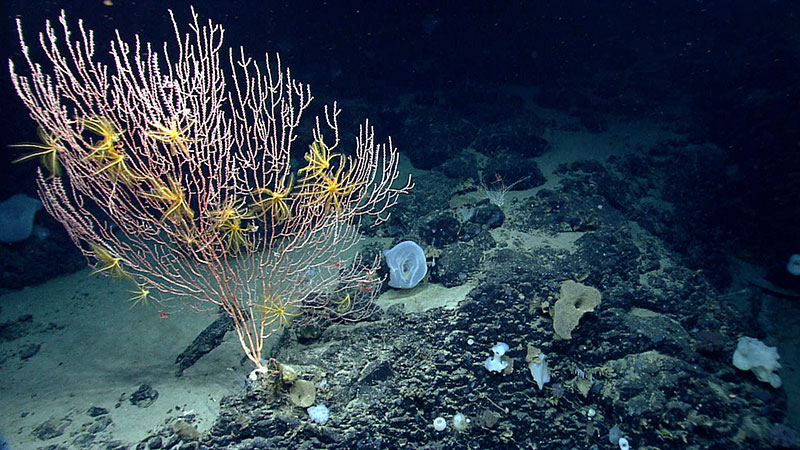

During a 2013 expedition along the northeast U.S. Atlantic coast, scientists observed that corals were diverse on Mytilus Seamount, but composition and abundance of corals differed between the north and south side of the seamount. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 1.6 MB).

There are four undersea mountains or seamounts within the Monument: Bear, Physalia, Retriever, and Mytilus seamounts. The seamounts are steep undersea extinct volcanoes. These seamounts are part of the New England seamount chain that resulted from a mantle-plume hotspot. This same mantle-plume hotspot created New Hampshire’s White Mountains as it migrated eastward under the North American Tectonic Plate. The Monument’s seamounts rise thousands of feet from the ocean floor, comparable to the height of the Appalachian Mountains. They are largely conical in shape, although wave erosion over time has caused some (e.g., Bear and Mytilus) to have a plateaued summit. Seamounts with a flattened top are referred to as “guyots.”

The seamounts are considered “biological islands in the deep sea.” They are ideal incubators for new life because of their isolation, unique topography, and current patterns. As currents flow up and around the seamounts, eddies can form, helping to keep larvae and other small organisms positioned over the seamount. In addition to encouraging larval settlement, these currents also bring food to the filter-feeding corals and sponges that grow in abundance here. Like the canyons, the substrate on these seamounts varies widely, resulting in a variety of species being found close together, leading scientists to refer to the seamounts as “ocean oases.”

The Monument is renowned for its rich and unique biodiversity, including deep-sea coral ecosystems and concentrations of marine wildlife. Its geographic features result in oceanographic conditions that concentrate pelagic or ocean-dwelling species, including whales, dolphins, and turtles, as well as highly migratory fishes such as tunas, billfish, swordfish, and sharks. A large number of seabirds also rely on this area for foraging, including Atlantic puffins.