By Dr. Amanda Demopoulos, U.S. Geological Survey

December 14, 2017

Small particles fall from the water surface as marine snow, blanketing the seafloor. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 353 KB).

As I sit in my office in north central Florida writing this mission log about marine snow, I can’t help reliving memories of snow ball fights and tobogganing down the hill by our house. While snow on land creates scenic landscapes and inspires hot chocolate consumption and relaxing by the fireplace, marine snow in the world’s oceans helps keep our oceans alive and healthy. But what is marine snow?

Marine snow originates in the surface waters of the ocean, primarily composed of phytoplankton produced through photosynthesis and microbes. As the material sinks, it collects other floating debris, including fecal material (poop), dead and decaying animals, suspended sediments (e.g., silt), and other organic material that may have been transported from the land to the sea.

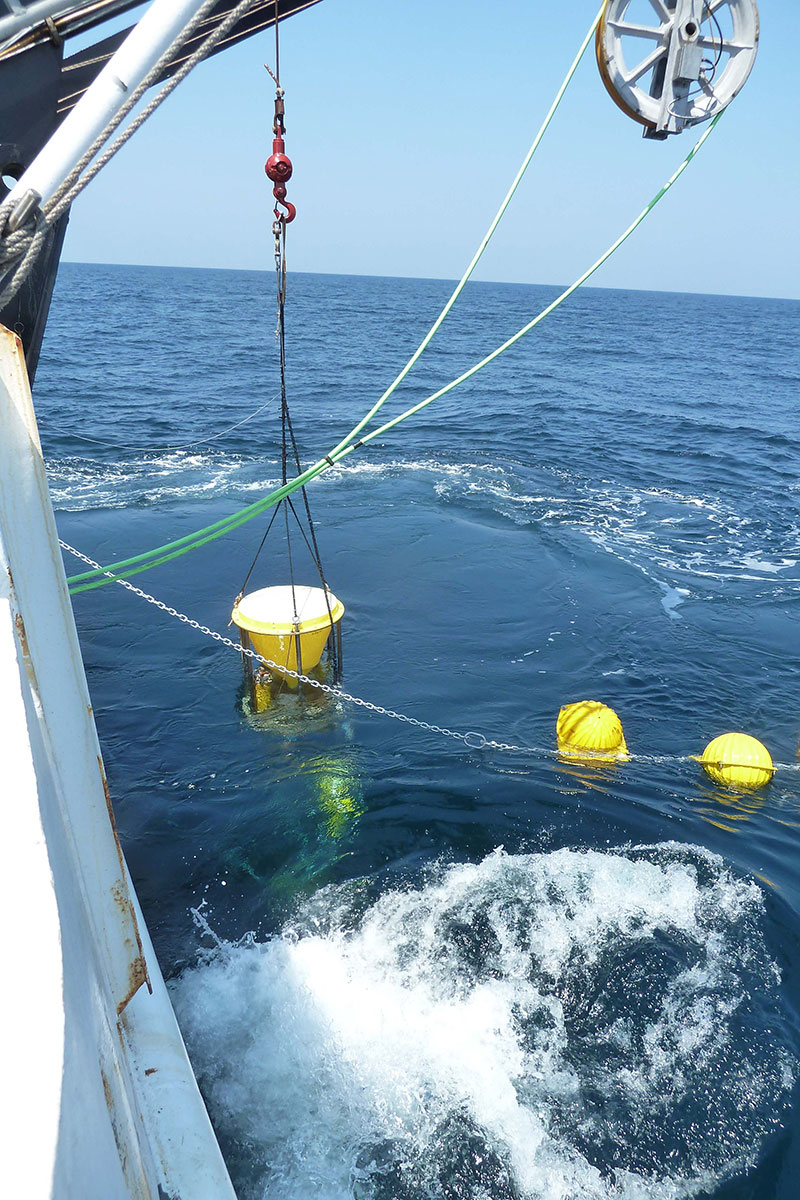

U.S. Geological Survey sediment trap and streaming floats being deployed off the stern of NOAA Ship Nancy Foster. Image courtesy of E. Hanneman, Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 3.1 MB).

Throughout the dives on this expedition, we have been observing marine snow in the water column; sometimes it is dense, reducing visibility, while in other locations it has been sparse. Why is this? Differences in the amount of marine snow falling through the water column, or density of this snowfall, is influenced by many factors, including production of phytoplankton in surface waters, consumption and decomposition rates of the organic matter en route to the seafloor, and the movement of this material via currents (horizontal and vertical).

The particles of marine snow grow as they sink, causing them to descend faster; however, the voyage to the deep can take weeks. How do we know this? Scientists use instruments called sediment traps; some are in the shape of a funnel, while others have a tubular appearance. As the snow falls through the water column, these traps collect and preserve the material, enabling scientists to examine the quality and quantity of marine snow over time. But why is it important to study marine snow?

Sea cucumbers, such as this one seen during Dive 08 of the Gulf of Mexico 2017 expedition, derive food directly from particles that have fallen from the water column and onto the seafloor. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Most of the animals that we have observed on the dives thus far, from suspension feeding corals to deposit feeding sea cucumbers, rely directly on marine snow. Other animals higher up on the food chain feed on animals that consume marine snow. So, while at seeps, certain organisms rely on chemosynthetically derived food, but most of the deep-sea inhabitants rely on food sinking from above. Thus, characterizing the quality and supply of this food helps us understand the distribution, biodiversity, and function of the deep-sea communities that we have been exploring on these dives.

While it would be difficult to start a snowball fight with marine snow, it is nonetheless a critical food source for ocean inhabitants and important for ocean health.