By Scott C. France - Science Lead, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

October 4, 2014

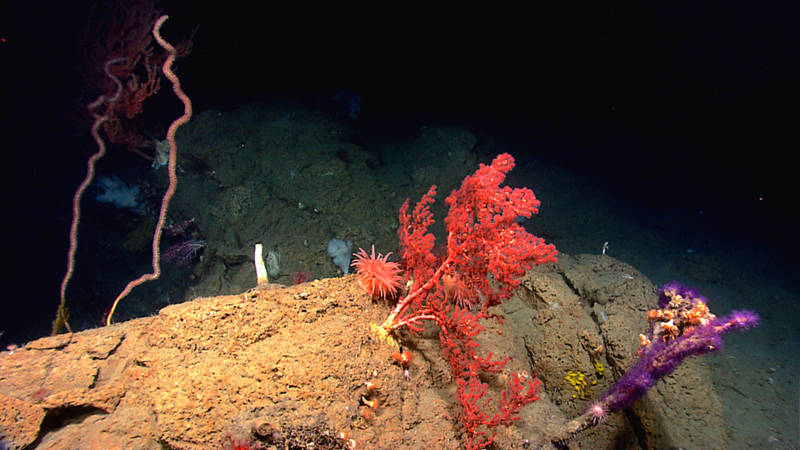

Benthic cnidarians are common in the deep-sea canyons and seamounts we are exploring. Here, octocorals, cup corals, and anemones share a rock at 1,459 meters depth in Hendrickson Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

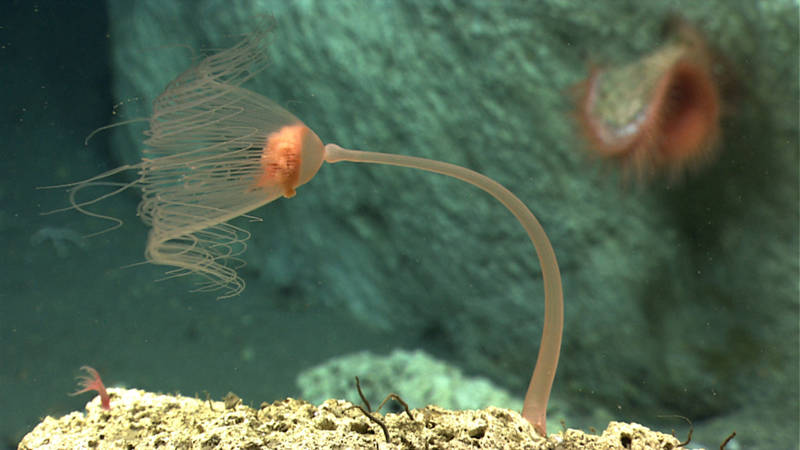

Benthic cnidarians come in all different shapes and sizes. Pictured here is a small Anthomastus octocoral (left), a solitary hydroid (center), and a flytrap anemone (background on the right). Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Let’s begin with some basic biology on the Phylum Cnidaria. This is the group of animals that includes the gelatinous-bodied jellyfish, Portuguese man-o-wars, and sea anemones. Most people are aware that jellyfish and other cnidarians possess stinging cells. In fact, the phylum is named for the microscopic, sub-cellular structures that do the stinging: cnidae (pronounced nye-dee). There are many types of cnidae, and not all of them sting, but only cnidarians can manufacture them in their cells.

Cnidarians have a very simple basic morphology: the body is essentially a bag or cup ringed by tentacles, with a single opening (mouth) into a digestive space (called the gastrovascular cavity) - food goes in and undigested food goes out this one opening.

The swimming body form of cnidarians, such as jellyfish, is called a medusa, and it is oriented with the mouth essentially pointed downwards. The cnidarians that live attached to a surface have a body form referred to as a polyp: here the mouth and the tentacles that ring it are oriented away from the bottom. Sea anemones and corals all have the polyp body structure.

Another way to consider the Phylum Cnidaria is their classification. The phylum is divided into four classes (perhaps more but that isn’t our concern here):

The class Anthozoa is broken down into two subgroups (subclasses): Hexacorallia and Octocorallia, each of which is further broken down into orders. The true anemones, corallimorphs, tube anemones, zoanthids, stony corals/cup corals, sea pens, and other octocorals all belong to different orders.

To better understand the meaning of the level of “order,” consider the mammals, which are a class of animals within the Phylum Chordata. Only mammals have hair, which is a major characteristic that groups them, but there are approximately 5,400 different extant (living) species of mammals. Mammalian species are arranged into 26 orders, including Chiroptera (925 species of bats) and Cetacea (83 species of whales and dolphins).

So, you can see the morphological difference between species in different orders is substantial, and there can be much species diversity within an order.

A pair of “true” sea anemones attached to the side of a rock at 2125 meters depth on Retriever Seamount. The anemone on the right has its tentacles folded over the mouth, showing the yellow-colored body, whereas the one on the left has the tentacles fully extended, showing the slit-like mouth opening in the center of the oral disk. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

So let’s review the different polyps we see often on the deep seafloor. True anemones, corallimorphs, tube anemones, and zoanthids all belong to the subclass Hexacorallia, but they each belong to a different order.

The true anemones (of the order Actiniaria) are likely the most familiar to people, being seen commonly in tide pools and aquaria. There are approximately 1,200 species and all are solitary polyps with tentacles that arise at the margin and/or from the disc and that are not pinnate (simple side branches that sometimes makes the tentacle resemble a feather). True anemones do not produce a skeleton.

A cluster of corallimorphs on a steep wall at 1,490 meters depth in Hendrickson Canyon. The corallimorph polyps have somewhat translucent tissue and white knobs at the tips of the tentacles that house dense clusters of the stinging nematocysts. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Corallimorphs (of the order Corallimorpharia) resemble true anemones in lacking a skeleton and in being solitary, but their internal morphology (such as details of the musculature) and cnidom (the various types of cnidae they possess) are more similar to that of a stony coral polyp (see below). Corallimorphs can be difficult to distinguish from true anemones – you may have heard me ponder this in the live video a few times. On average they tend to be shorter with a wide oral disc and tentacles with whitish bulbous tips (because they are packed with stinging cells!); there are only about 25 species described.

A cerianthid tube anemone in its flexible, felt-like tube at 1,510 meters depth in an unnamed canyon east of Veatch Canyon. The tube may be buried more than a half meter into the soft sediment. Tube anemones have two rings of tentacles: the long ones around the margin, and inside of those, shorter ones directly around the mouth. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Tube anemones (of the order Ceriantharia) are burrowers that inhabit a flexible, felt-like tube they build from a unique type of cnida (which we call the “ptychocyst”) that binds mucus and grains of sand or mud.

The polyp body is elongate with a ring of short tentacles around the mouth in addition to the long marginal tentacles. There are about 100 species of tube anemones described.

A colony of sand-colored zoanthid polyps overgrows an octocoral skeleton at 2,046 meters depth on Kelvin Seamount (the bright white branches on the left are the only remaining living tissue of the octocoral, Corallium). The columns of the polyps are rough-looking due to the sand and mud grains and other debris embedded in the tissue of the zoanthid. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Zoanthids (of the order Zoanthidea) have two rows of marginal tentacles and lack a skeleton, although the polyps often incorporate sand grains or debris into their column walls and thus look very rough or thick.

Many zoanthids are epizoic, meaning they prefer to grow on other animals such as sponges and corals. Zoanthids are clonal (bud off new individuals by asexual reproduction) and often form true colonies. A colony is a body form where multiple individual units – called zooids – are connected by common tissue to form a sort of super-individual. The gastrovascular cavities of all the zooids in a colony are interconnected.

A pair of cup corals (Scleractinia) grow from the wall of an unnamed canyon east of Veatch Canyon at 1,480 meters depth. You can see the transparent maroon-colored tissue and tentacles of the polyp overlying the white calcareous skeleton; the narrow plates visible below the tentacles are the septa of the calyx. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Stony coral polyps (of the order Scleractinia) sit on a solid calcareous skeleton that they secrete. Individual cup-like pockets (“calyces”) of the skeleton are subdivided by septa (thin sheets) and polyps can retract into them for protection.

Stony corals may be either solitary or colonial. The cup corals we have been seeing often on these dives are solitary—they do not form colonies where polyps are connected. Most of the well-known, shallow-water tropical stony corals that make up coral reefs are colonial.

A small colony of the black coral Bathypathes at 2,004 meters depth on Retriever Seamount. The black coral polyps are so small, and the tissue on the skeleton so thin, that the tentacles appear to arise directly from the branches. In this group of black corals, the polyps are stretched out along the branch so that instead of a ring of six tentacles surrounding the mouth, the tentacles arise in pairs, with the central pair flanking a raised cone that bears the mouth. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Another group of corals in the Hexacorallia are the black corals (of the order Antipatharia). All are colonial and produce a thorny skeleton. The polyps are quite small, with exactly six tentacles, and sit on very thin tissues wrapped around the skeleton.

Sometimes it almost looks like the tentacles are arising directly from the tissue on the skeleton instead of from a polyp body. The group gets the name from the black color of the skeletons, but the polyps can be orange, white or yellow.

There are about 230 species of black coral described.

The tip of a bamboo coral (Lepidisis sp.) colony reaches off the seafloor at 2,048 meters depth on Kelvin Seamount. Tentacles of the polyps have been retracted over the mouth, thus revealing the needle-like sclerites of this species that extend from the polyp body and serve as a form of defense. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

As noted previously, octocorals belong to a different subclass from the hexacorallian orders. There are approximately 3,000 extant species of octocorals and virtually all are colonial (there is always an exception!).

Close-up of a sea pen colony at 2,023 meters depth on Retriever Seamount. Sea pens are octocorals and the characteristic eight pinnate tentacles are plainly visible in this image. The dark line running down below the tentacles of each polyp is the pharynx, connecting the mouth to the bag-like digestive cavity. A mysid shrimp (“possum shrimp”) is swimming by the colony. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

The polyps of octocorals are usually easily recognized because they have eight pinnate tentacles encircling the mouth. They also have sclerites embedded in their tissues. Sclerites are hardened micro-structures made of calcium carbonate and come in a bewildering array of shapes and sizes and are used in the taxonomy and identification of octocoral. Occasionally you can see sclerites in the remotely operated vehicle close-up video (especially the needle-shaped ones that protrude between the tentacles).

Octocoral colonies in the order Alcyonacea may have an internal skeleton (and are thus usually referred to as a sea fan or sea whip), or lack a skeleton (soft corals) or grow as a mat or ribbon (stolonferous octocorals). Sea pens (O. Pennatulacea) are octocoral colonies adapted to live in soft bottoms, so we typically see them when we cross over muds and sands, although there are a few species, referred to as the “rock pens,” that live on hard bottoms.

A Giant Solitary Hydroid at 2046 m depth on Kelvin Seamount. The Solitary Hydroid has two rings of tentacles, with one set (which look like a pink tube surrounded by the longer tentacles in this photo) being very short and arranged around the mouth. The whitish balls of tissue between the two rings of tentacles are reproductive structures. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Finally, one other very impressive cnidarian polyp we have encountered several times is the giant solitary hydroid, which, as this name suggests, is in the Class Hydrozoa and not Anthozoa (as are all the previously described polyps).

The solitary hydroid has two rings of tentacles, with one set being very short and arranged around the mouth. The internal anatomy of the hydrozoan polyp is simpler than the anthozoan polyp. An interesting twist is that the reproductive organs are produced in masses in between the two rings of tentacles, rather than on the inside of the polyp (as in the anthozoans).

Hydrozoan polyps may release small jellyfish from these organs; these hydromedusae swim away to find mates with which they exchange gametes to produce larvae that settle to grow into a new polyp. This is different from the anthozoan,s which all lack this medusa stage in their life cycle.

We see many delicate, feather-like hydroid colonies and solitary polyps during our dives, but they are typically too small to see any detail, or even tentacles, and one of the reasons the giant solitary hydroid is so exciting to find.