By Robert S. Carney, Professor of Oceanography - Louisiana State University

April 3, 2012

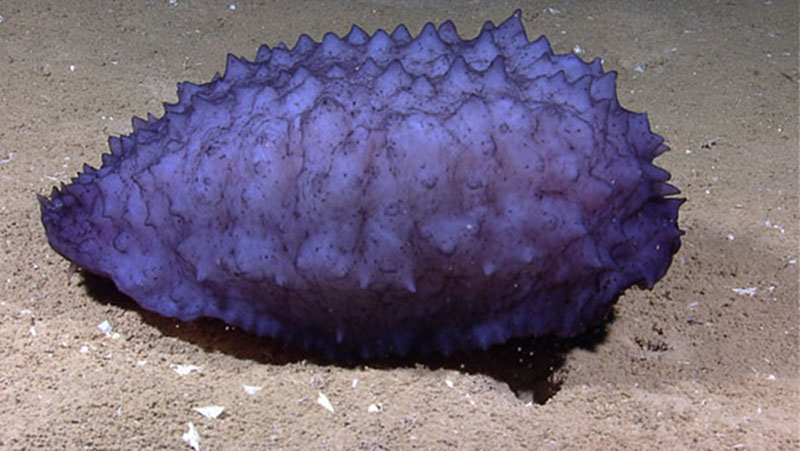

Benthothuria and escape swimmer: When disturbed by the remotely operated vehicle, Benthothuria flexes its body and empties its gut of heavy sediment. Having come off bottom, it remains suspended due to the neutral buoyancy of its thick purple body wall. Somehow it gains enough weight to sink and resume feeding. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download image (jpg, 12 KB).

Holothuroids, also called sea cucumbers, are an unusual class of the unusual phylum Echinodermata, which literally means animals with spiny skins.

Echinoderms have a long list of traits that distinguish them from other invertebrates. Most conspicuous is the pentaradial (based on five) symmetry of the bodies seen in seastars, brittle stars, sea urchins, chrinoids, and many extinct taxa. All of these animals have a complex hard outer surface with many special structures including spines and plates made of a special calcite matrix. Echinoderms also have a special type of connective tissue, the elastic properties of which can be controlled by the animal.

Holothuroids are a class of echinoderm which usually have a soft body inflated by the water pressure of the body cavity (called a hydrostatic skeleton). Externally, they are more bilaterally symmetrical than pentaradial.

Holothuroid species fill many ecological niches from shallow water to the greatest ocean depths. They are especially numerous on the deep-sea bottom.

Sea Cucumber I. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download image (jpg, 63 KB).

Sea Cucumber II. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download image (jpg, 85 KB).

Sea Cucumber III. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download image (jpg, 38 KB).

With so many species, how do scientists identify and name these sea cucumbers? You might be surprised to know it is typically by genus. Hjalmar Theel studied the deep holothuroids collected by the voyage of the HMS Challenger and published most of the results in 1882. Although he examined only badly damaged, alcohol-preserved specimens, he came up with an appropriate genus name, Enypniastes, for this water dancer. Enypniastes means "dreamer." He also identified and named the genus Scotoplanes, which means "swimmer in darkness" and is closely related to Peniagone, or "spawn of poverty,” a name probably alluding to the low level of food available to deep-sea animals.

When we can get such detailed close-up video portraits of the deep Gulf of Mexico holothuroids such as those captured by the Little Hercules camera, why do we leave identifications at the level of genus rather than species?

Pioneering study of holothuroids was all based on animals from caught by trawling, which badly mangled specimens. Specialists like Theel did not even witness the animals being collected. Specimens were preserved in alcohol, which bleached the colors out of samples shipped to him.

To understand holothuroid identification, we return to a basic trait of echinoderms, hard structures in the skin made of an elaborate calcite matrix. In soft-skinned holothuroids, these are small shapes in the skin called ossicles or spicules. Many holothuroids can only be identified to species by studying the spicules under a microscope, an optical task beyond the best ROV camera available.