By Dr. James (Jamie) A. Austin, Jr., Science Lead, Expedition 3 - Senior Research Scientist, Institute for Geophysics, Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin

April 15, 2012

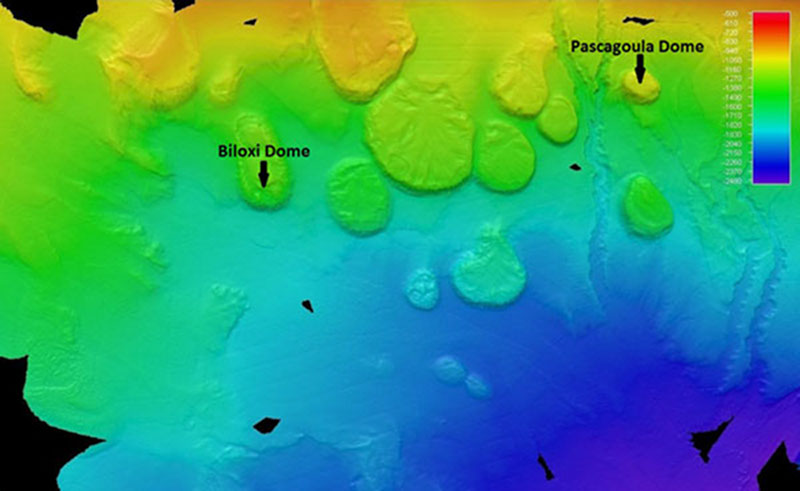

The seafloor off the coast of southeastern Louisiana. Greens and Orange represent the shallowest water - green is deeper - and blues represent the deepest water. The tops of salt domes are the more or less flat-topped circular features. Sometimes the salt cores get near the seafloor itself; sometimes, the core remains buried by younger sediments. The dome tops in this picture are some of hundreds in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 430 KB).

The third leg of the Okeanos Explorer Gulf of Mexico mission is operating in a part of the Gulf, the oldest sediments of which are part of the upward-moving Louann Formation. This large deposit of evaporites/salt was deposited about 160 million years ago when the Gulf of Mexico formed, as the continent of South America moved away from North America, a plate separation process known as rifting.

At diapirs or salt domes, sometimes the salt itself actually reaches the seafloor where it dissolves, occasionally filling lows in the seafloor with super-saturated, very dense salty waters known as brines. We may dive on one of these "brine pools" during Leg 3. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 51 KB).

Within this rift, seawater rushed in, but was periodically evaporated by the narrowness and complex geography of the rift, leaving vast deposits of salt behind. Over the millions of years since, that salt has been loaded – pushed down and weight added – by many kilometers of younger sediments. Because the salt is less dense than the sediments above it, it begins to rise in fantastic pillars known as diapirs, piercements (because they “pierce” the overlying material), or salt domes. Many of these domes have now reached the seafloor, as can be seen in the figure showing the seafloor off southeastern Louisiana.

The Pascagoula and Biloxi domes are two examples of these piercement structures. Sometimes the salt itself actually reaches the seafloor, where the salt dissolves, occasionally filling lows in the seafloor with super-saturated, very dense salty waters known as brines. We may dive on one of these "brine pools" during Leg 3. The architecture of these rising salt-cored domes is complicated; they deform the sediments above them. This complexity is one of the main reasons the Gulf of Mexico is the important oil and gas province that it is. The structures produced in the subsurface trap gas and oil against the salt, which itself is impermeable, so those hydrocarbon fluids pond against the sides of the salt, where they can be found and extracted.

The Gulf of Mexico is not the only "salt province" in the world's oceans. Other major provinces occur off the east coast of southern South America and the west coast of central Africa. All are major oil and gas provinces.