Into the Abyss

[an error occurred while processing this directive]Free Diving

1926

Diving in the Sargasso Sea

Cover to Nature Notes for Ocean Voyagers by Alfred Carpenter. NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 121 KB).

"I dived and entered an ultramarine world, with sprigs of amber sargassum weed floating near the ceiling of that world. Tiny fish darted past, and once, even with the dullness of my aquatic vision, I saw a small school vanish from view - a group of timid flyingfish which took to wing and entered the air at sight of my strange appearance. I dived a second time and sank as low as my stored-up breath permitted, and then before I turned and kicked upward, took one long look beneath and tried to imagine that unimaginable world of life down, down in the ever blackening, ever greater pressured depths. No ship or companion was visible and my sense of devastating isolation, of cosmic awe can never again occur with equal force in this life...

"Here then in the midst of the sea, for a moment, I peered down toward the mid-ocean ridge which Wagner [sic, actually Wegener, the formulator of the theory of continental drift] would use to fill up a chink in his continental mosaic; which some would have as the site of old Atlantis, or others strew with the weed-caught wrecks of ancient galleys, medieval ships, and modern dreadnaughts. But no theory, whether plausible or incredible, could ever people these depths with beings stranger than those piscine elves and hobglobins which we were soon to draw up into the light and warmth of our daylight.

I followed the last stream of my life-bubbles to the surface ..." describing a free dive in the Sargasso Sea in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. In The Arcturus Adventure (1926) by William Beebe. Published by G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York. pp. 36-37.

1951-1

Free Diving Versus Helmet Diving

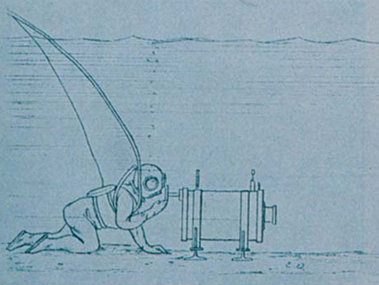

Boutan's method of obtaining instantaneous photographs of fish. In "The Photography of Aquatic Animals in Their Natural Environment" by Jacob Reighard, (1907). Bulletin of the Bureau of Fisheries, Vol. XXVII, pp. 41-68. NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 28 KB).

"I liked to use my face mask more than the diving helmet for most occasions. I was learning to hold my breath longer now and could go down almost as deep without the helmet which limited my movements..." In Lady with a Spear (1951) by Eugenie Clark. Published by Harper and Brothers, New York. pp. 51.

1951-2

An Expert Diver

"Professor Hiatt and I wore face masks and the Fisheries Director, Vernon Brock, who ordinarily wore strong glasses, had special underwater goggles with ground lenses. Mr. Brock also wore frog's feet and had a spear.

"The water was blue and incredibly clear. I swam around near the surface, looking down at the magnificent reef below. I watched Mr. Brock dive to almost forty feet while he explored the cavernous reefs among which thousands of gorgeous tropical fish were living. Then slowly, with the maneuvers of an expert underwater swimmer, Mr. Brock followed a huge green parrot fish and after a quick thrust he had it flapping on his spear as he swam back to the surface. It was a thrilling capture to watch but even though I hadn't wanted to miss a moment of it, I had been forced to lift my head out of the water briefly several times during Mr. Brock's single-breath dive. I vowed that someday I would learn to use a spear and catch fish this way in their own environment. In comparison, how dull it is to sit up in the airy world and pull a fish out of the water on a line!" In Lady with a Spear (1951) by Eugenie Clark. Published by Harper and Brothers, New York. pp. 40-41.

For thousands of years, our observations of the sea were confined to what they could observe from the surface of the sea or from the seashore. A few intrepid divers risked their lives by plunging into the sea and holding their breath as long as humanly possible, or by working in enclosed caissons while engaged in submarine construction or salvage operations. For the most part, these early excursions into the undersea world had only immediately practical objectives - the search for sustenance or sunken treasure, work on construction projects, or attempts to gain military advantage. With the exception of a few classical observations, the scientific study of the sea from within is a relatively recent phenomenon.

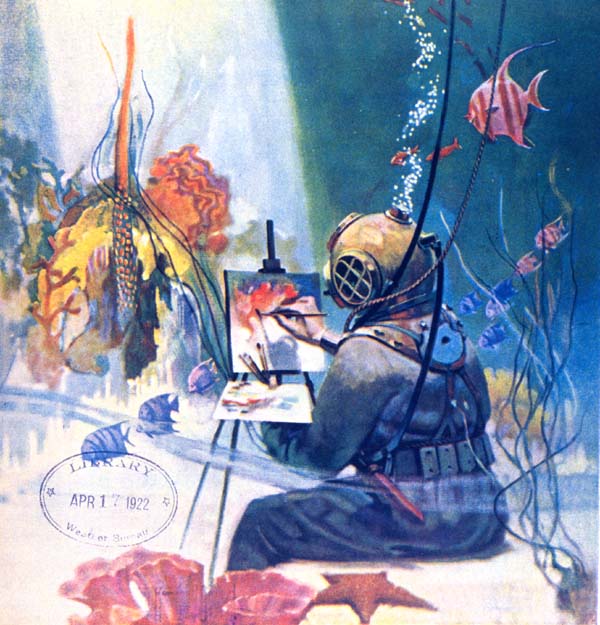

Hard hat diver capturing his views of the wonders of the deep. (Courtesy of NOAA Photo Library.) Download image (jpg, 106 KB).

People began their study of the sea by peering into the waters from vessels or by walking along the seashore. They progressed to free diving, then helmet diving, and finally to the use of SCUBA, which stands for self-contained breathing apparatus. Crushing pressure constrained the unprotected diver to the first few hundred feet of the water column; to overcome the limitations imposed by the environment, the first vehicles to carry scientific observers into the abyss for scientific observation were constructed less than 75 years ago. Today, many scientific diving vehicles routinely carry scientists into the sea to observe marine life, study marine geological processes, and conduct physical oceanographic observations. The following quotations help track some of the milestones and observations made along this journey into the abyss.