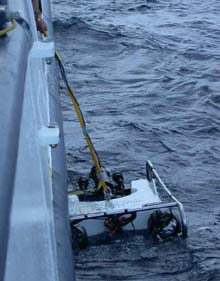

Scientists are using this Phantom S2 ROV to identify and map the habitats on Oculina Bank. ROVs of this class can be launched over the side of a ship and do not require cranes or hoists for deployment or recovery. Click image for larger view.

A Brave New World of Exploration at Oculina Bank

August 29, 2001

Andrew Shepard, Director

National Undersea Research Program University of North Carolina at Wilmington

Since early in the 20th Century, a debate has flared over the role of robots in science, industry and other aspects of life. "Should robots take he place of people for certain mundane, repetitive or dangerous work?" The debate further inquires, "Can robots perform the tasks of scientific exploration and discovery better than a human being?" The question is relevant to the Islands in the Stream/South Atlantic Bight Mission to Oculina Bank, where both robotic instruments and direct human observation will be used to map different types of habitat and then to quantify the extent of Oculina varicosa, a delicate species of deep branching coral.

The manned submersible Clelia after recovery during its first dive at Jeff's Reef on Oculina Bank. From left are Tim Askew, Jr., submersible pilot; Jimmy Nelson, swimmer; and Sandra Brooke, a scientist observer. Click image for larger view.

Not surprisingly, pros and cons exist both for using a robot or remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and a human-occupied vehicle (HOV or manned submersible) in ocean science. The major advantages of an ROV are human safety and the ability to conduct continuous operations. In the intense underwater pressure of the marine environment, ROVs eliminate the risk of certain accidents that would have dire consequences to the occupants of manned submersibles. The failure of pressure seals or the life-support system that provides oxygen and removes carbon dioxide within an HOV is not a concern in ROVs. Furthermore, the failure of devices such as camera housings, which are mounted on the outside of an HOV, could result in serious damage, such as hull failure to the vehicle. Finally, ROVs can operate round- the-clock. In contrast, due to safety concerns, shipboard recovery of manned submersibles can often restrict operations to daylight hours or to times of calmer sea states.

Generally, manned submersibles have a greater payload size, provide their occupants with a three-dimensional view of their submarine surroundings, and have better dexterity of movement. In the eyes of marine scientists with a deep and burning desire to explore, however, the HOVs' greatest advantage is their ability to provide direct access to the unknown. Diving into an environment that can be simultaneously hostile and foreboding, yet fascinating and beautiful, captivates many scientists, enabling them to find the answers they seek based on first-hand experience.

A small sample of Oculina varicosa, also known as ivory tree coral, collected for genetic analysis to determine the source of the species' spawning stock.Click image for larger view.

In the case of Oculina Bank, where there is concern that fishing activities have seriously damaged the Oculina coral heads, a serious need exists for a habitat map and quantitative assessments of the extent of the coral. During this mission, ROV and manned submersibles will complement each other in the quest to understand exactly how much Oculina coral remains on the bank. ROV operations will provide scientists with a relatively rapid reconnaissance and assessment of the types of bank habitats. This information will allow them to better direct the precise locations for HOV operations, where the distribution and abundance of Oculina can be studied and quantified. The scientists on this expedition are playing on the strengths of both types of technology.

Today's Explorations

Today, two submersible dives were conducted at Jeff's Reef, at the southern end of Oculina Bank, between the depths of 240 and 260 ft. This area has some of the healthiest and most intact coral colonies of the entire bank. On the first dive, samples of Oculina were brought to the surface for genetic analysis to help determine the source of spawning Oculina stock. The genetic analysis will determine more about the natural reproductive capacity of this coral and the extent to which artificial reefs could help supplement natural colonization. The ROV was also deployed at Jeff's Reef, to text its maneuverability and operator control in the three-knot Gulf Stream current. Later in the mission, it will help support visual observations of habitat using the manned submersible.

A head of Oculina coral, approximately 3 ft in diameter, observed during the first dive of the mission. Note the dark material covering the coral. Click image for larger view.

Chris Koenig and Sandra Brooke, scientist observers in the Clelia, reported that the habitat looked reasonably good in this location with no signs of bottom-trawling activities. They reported seeing "tons" of amberjack.

While some ocean scientists may argue that manned submersibles will one day be replaced by ROVs or even by autonomously operated vehicles (vehicles without tethers) that can be programmed to navigate by an on-board computer, many others would argue that there is a role for the human observer and that manned submersibles are here to stay. Judging from the interest of the scientists aboard this expedition, everyone wants to get beneath the surface to have a look for themselves, whether exploring through a video screen linked to an ROV or peering through the porthole of a submarine.

Interview with Lance Horn, Remotely Operated Vehicle Pilot

Lance Horn is the operations manager for the National Undersea Research Center at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. He is one of the best, most experienced remotely operated vehicle pilots (ROV) pilots in the country. He is running a Super Phantom ROV during the expedition -- no easy feat in 4- knot currents over rugged terrain.

Ocean Explorer: How long have you been "flying" an ROV, and what stimulated you to become an ROV pilot?

Lance Horn: I began piloting ROVs at NURC in 1987. It happened somewhat by accident. When I was in school at the Florida Institute of Technology, I was trained as a hardhat diver, the type that wears a large, round helmet and is attached to a surface ship with an air-supply tether. So when I first went to work at NURC, I became a surface supply diver. But after a while, the center wanted to see and cover more water than one could with surface supply diving. We used scuba, and I learned to operate ROVs down to 1,000 ft. The center leased submersibles to cover the entire water column. Since I've always been mechanically inclined, I became an engineer on one of the NURC vessels, and when the vessel acquired an ROV, the captain put me in charge of learning how to use it.

Lance Horn "flying" the ROV near the bottom of Oculina Bank and enjoying the view on the monitor. Note the gray control box in his lap. The forward speed of the ROV on this dive is about 1 knot. Click image for larger view.

Recovering the Phantom S2 ROV alongside the Seward Johnson II on Florida's Oculina Bank.

Ocean Explorer: What are the biggest challenges, greatest difficulties, and most rewarding aspects of being an ROV pilot?

Lance Horn: Probably the biggest challenge is doing the science that scientists want to do. A lot of times, they expect more than the ROV can do. They might want to overload it with too much equipment, or they want it to go into places where it might get stuck, or where currents make it difficult to control. On Oculina Bank, there is quite a bit of rugged, high-relief terrain where the ROV could easily become lodged in a crevice. Also, the currents here are sometimes so fast that it's very tricky to set the ship speed and direction for the ROV.

Most rewarding is seeing scientists get excited, or seeing some totally unexpected fish behavior, or chasing a fish to observe it longer. Search and recovery of equipment that is stuck on the bottom or malfunctioning also is very satisfying.

Ocean Explorer: What do you see as the major advantages and disadvantages of an ROV as compared to a manned submersible?

Lance Horn: A manned submersible gives you a wider field of vision, whereas an ROV looks straight head. The advantage of the ROV is that it's highly mobile. Also, it can be used on virtually any ship and can stay below the surface indefinitely. Most manned submersibles can only be launched from a couple of ships that have been outfitted to handle them. The ROV complements the submersible. It can scout the areas where scientists want to dive in the submersible. The sub usually has a greater payload capacity and can be fitted with more instruments to collect samples of sediments, fishes and invertebrates.

Interview with Don Liberatore, Chief Submersible Pilot for Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, Fort Pierce, FL

Ocean Explorer: How long have you been a manned submersible pilot? What was involved in your training, and how long did it take?

Don Liberatore: I became a qualified sub pilot in 1980. It took me 2-1/2 yrs to get my pilot qualifications, working my way up from a position as a diver medical technician. I obtained the medical training during a 2-yr program in underwater technology at the Florida Institute of Technology. Then, the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute hired me to dive and run a decompression chamber. Divers were needed in the oil industry when I started the FIT program, but when I graduated in 1977, the oil industry had dumped a lot of divers. I was lucky to find a job assisting the scientists at Harbor Branch.

The first year, I was a lockout diver (one who exits a pressurized "lockout" chamber on the ocean floor). I ran the decompression chamber the second year. Since then, I've worked up to chief pilot and I now have a crew of 10. People can train to become sub pilots after being on the crew for some time and demonstrating that they are suitable for the job. A sub pilot needs to be calm and able to take care of problems as they arise. They start by learning the sub's electronic and pneumatic schematics from manuals. I'd advise people interested in learning sub piloting to start as an electrical technician.

Ocean Explorer: How many dives have you made? In what parts of the world's oceans have you dived? Which are the most memorable areas, and why?

Don Liberatore: As a pilot, I crossed the 1,500-dive mark on this expedition. Yesterday was number 1,502. I'd estimate my total number of dives, during training and as a passenger, at 2,000. I've been in the Atlantic all along the U.S. East Coast -- that's like our backyard -- and in the Gulf of Mexico from Florida to Galveston, TX, and around Mexico, the Yucatan, and Cancun. In the Caribbean, I've been to every one of the big Bahamian Islands, and to Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, Honduras, and Panama on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides. I've been to the Galapagos Islands three times, where I worked on films for the Discovery Channel and IMAX. I've dived the Mediterranean as far east as Monaco, and the Atlantic off the coast of western Africa. I've also dived in the Great Lakes. In Lake Superior, I dived to the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, and I have also dived to the wreck of the USS Monitor off the coast of North Carolina.

From a natural point of view, each area has its goodies. The Galapagos were really exciting because it was all new to us; no one had piloted at such great depths (3,000 ft) before, and the wildlife was really spectacular. In the Bahamas, I remember unusual water clarity and unbelievably spectacular shallow-water reef life, both in appearance and abundance. In deep water, I saw huge, pure white, tuba-shaped sponges sticking out of sheer limestone walls.

One very interesting experience was meeting Cuban Head of State Fidel Castro and showing him around the sub. Regardless of politics, it was exciting to meet a historic figure. I also worked for three months on recovery operations for the Challenger Space Shuttle.

Ocean Explorer: What is the most difficult and challenging aspect of piloting a marine submersible?

Don Liberatore: It's definitely the currents. They are the biggest factor. When it's ripping along at 2 or 2.5 knots, such as we've encountered on this trip, it's difficult to do anything but hang on. You're always getting swept sideways. It's like being an airplane pilot flying through a thunderstorm. On Oculina Banks, the currents spill over the top of 40-to-50-ft mounds and push you down. The subs are underpowered and don't have enough thrust to deal with those conditions. Ballast control is one of the most important parts of training. Having the right weight and correct positioning of the weight affects maneuverability. That's why pilots don't like to see last-minute gear coming on board.

Most places have some current, and at .5 knots, it's manageable. No current at all can be a problem, too. If you stir up the silt with the sub and there's no current to clear it out, you've just lost a half-hr of dive time waiting for the silt to settle.

Don Liberatore inside the Clelia, giving scientific observers (unseen below) their safety briefing prior to launch.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.