By Rear Adm. Sam Cox, U.S. Navy (Retired), Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

August 15, 2018

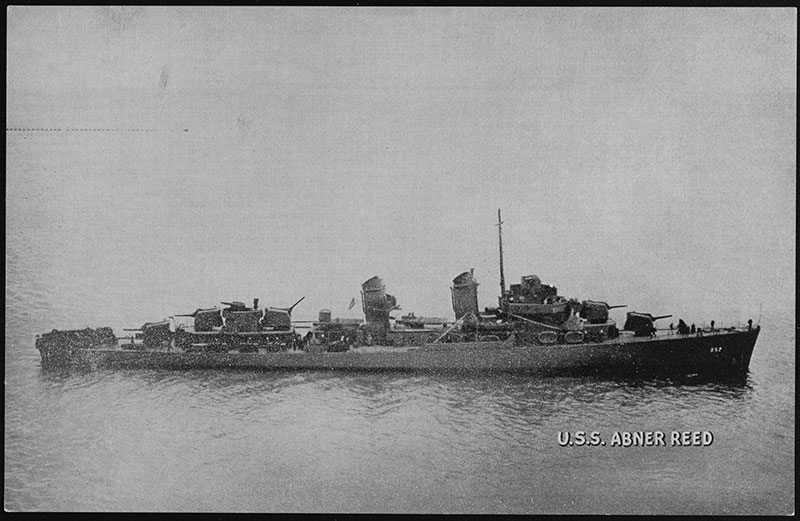

USS Abner Read (DD 526). Halftone reproduction of a photograph taken circa April 1943, showing the ship as first completed. This image was retouched by wartime censors to eliminate radar antennas atop the foremast and Mark 37 gun director. It was also published reversed, so the bow points right instead of left. Released/U.S. Navy Photo from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. Download larger version (jpg, 8.9 MB).

The waters off Alaska and in the Arctic have long been key strategic areas. In World War II (WWII), both the U.S. and Japan understood this and committed men and vessels to the area. Most people are aware of the historic Battle of Midway – but there was a complementary effort that took place in the Aleutians Islands at the same time between our navies.

It was there, in the crucible of combat, in spite of the demands of the maritime environment, that American Sailors enabled regional freedom and prosperity, deterred aggression, and assured allies through their integrity, initiative, toughness, and valor, traits that remain the hallmarks of today’s Navy.

On August 18, 1943, USS Abner Read (DD 526) was on patrol off Kiska Island, Alaska. Although the Japanese had already evacuated Kiska, they left behind sea mines. Abner Read struck one such mine in the dead of night, and the force of the explosion blew the stern off the ship. The stern quickly sank, taking the lives of 71 of her crew and leaving another 47 wounded.

Despite the surprise, shock, and loss of so many of their shipmates, the surviving crewmen of Abner Read displayed extraordinary valor and determination in saving their ship from the catastrophic damage that by all rights should have sunk their entire ship. But the crew of Abner Read refused to go down without a fight. And fight they did; the crew’s absolute refusal to give up their ship no matter what provides an inspiration to the Sailors who serve our nation today.

USS Abner Read (DD 526), bow view. Hunters Point, California, June 13, 1943. Released/U.S. Navy Photo from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. Download larger version (jpg, 10.3 MB).

Recently, the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research sponsored a project to survey underwater sites related to the WWII Aleutian Island campaign, in search of pieces of the Navy’s historic valor and sacrifice. Researchers from the University of Delaware, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, and Project Recover discovered the stern section of the WWII destroyer. The wreckage was found using the multibeam sonar and then investigated using a small remotely operated vehicle (ROV) on a non-disturbance observation dive. It’s discoveries like this that remind us of our past and the heroism each Sailor may need to call upon.

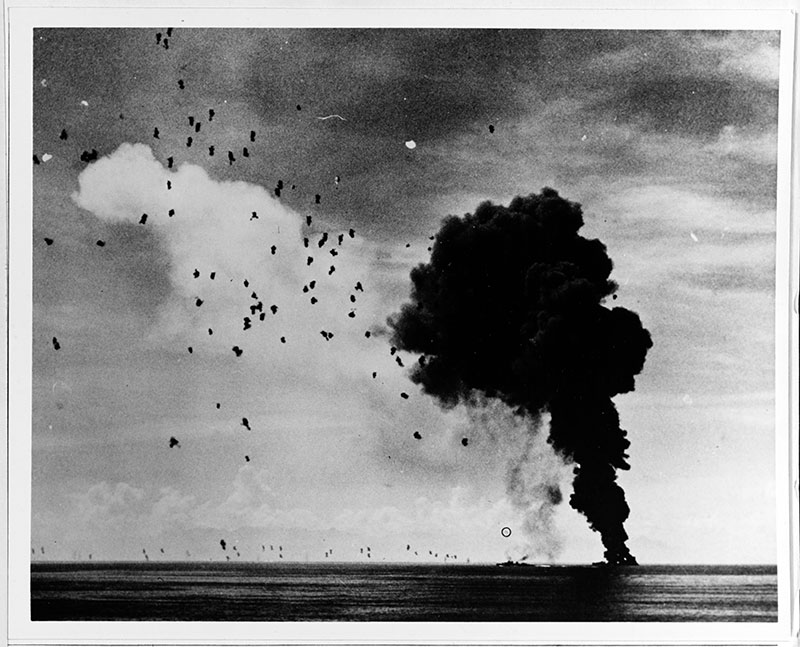

Not only was Abner Read saved that day, she lived to fight another day. The ship and crew later returned to the Pacific theater and participated in a number of important engagements. But the ship’s luck ran out on November 1, 1944, when, at the famed Battle of Leyte Gulf, an attacking Japanese “Val” aircraft burst into flames and crashed toward Abner Read. A bomb from the raider dropped down one of the destroyer’s stacks and exploded in her rear engine room and the aircraft crashed diagonally across the main deck, setting fires which caused significant damage topside. The ship lost water pressure, rendering firefighting efforts impossible. A little more than 30 minutes after the Val burst into flames, Abner Read rolled over on her starboard side and sank stern first. All but 22 members of the crew were rescued.

USS Abner Read (DD 526) afire and sinking in Leyte Gulf, November 1, 1944, after being hit by a kamikaze. A second Japanese suicide plane (circled) is attempting to crash another ship; however, this one was shot down short of its target. Released/U.S. Navy Photo from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. Download larger version (jpg, 8.7 MB).

The discovery of the stern section from the mine strike in 1943 is a testament to the rich history and heritage of the U.S. Navy and the honor, courage, and commitment with which Sailors of all generations serve. Thanks to ships like Abner Read and the crews who served in them, we are able to build on that courage to be a more capable force today. I am encouraged by this development and look forward to reviewing the data once it is made available. The Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) is grateful to NOAA and the entire project team for the dedicated efforts to search for and provide evidence of the nation’s and the Navy’s rich maritime heritage of courage, valor, and determination.

Upon discovery, Abner Read’s stern section becomes part of NHHC’s Underwater Archaeology Branch’s (UAB) cultural resource database. As stewards of the Navy’s 2,500 shipwrecks and 14,000 aircraft wrecks, UAB ensures Navy compliance with federal laws and regulations as well as develops, coordinates, reviews, and implements historic preservation and cultural resource management policy.

In the interest of preserving and protecting these sites, the Navy generally does not release the precise locations of historic wrecks for which we have the coordinates. The Department of the Navy’s sunken ship and aircraft wrecks make up a global collection of fragile, non-renewable, cultural resources that often serve as war graves, safeguard state secrets, carry environmental and safety hazards such as oil and ordnance, and hold historical value.

There are currently no recovery plans. Consistent with the longstanding traditions and practices of seafaring nations, the U.S. Navy recognizes the sea as a fit and final resting place for those who perish at sea. The U.S. government takes any desecration of shipwrecks, especially war graves, or unauthorized disturbance of any other sunken military craft, very seriously. The wrecks are a testament to the Sailor’s sacrifice who served and their protection reflects the Navy’s obligation to never forget their service and sacrifice.