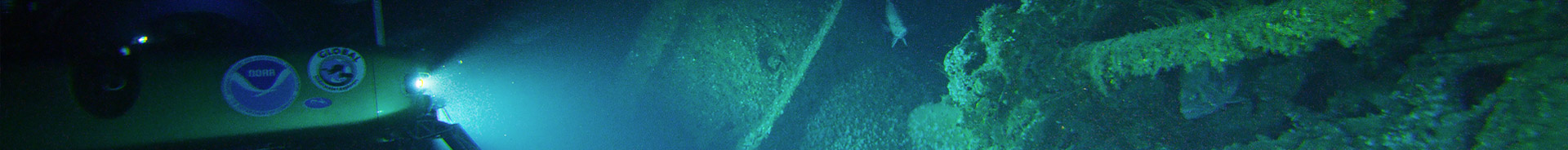

Joe Hoyt, Maritime Archaeologist - NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

Crew of U-576 at watch in the conning tower. Photo courtesy of the Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 3.0 MB).

On July 14, 1942, the convoy KS-520, with 19 merchant ships and five escorts, set sail from Hampton Roads, Virginia. The convoy code ‘KS’ that identified the group indicated that they were moving south along the eastern seaboard with Key West, Florida, as their final destination after a seven-day sail through U-boat infested waters. The convoy of ships assembled once they passed the minefield protecting the Chesapeake Bay, set a course for 78 degrees, and headed south at a slow but steady speed of 8.5 knots.

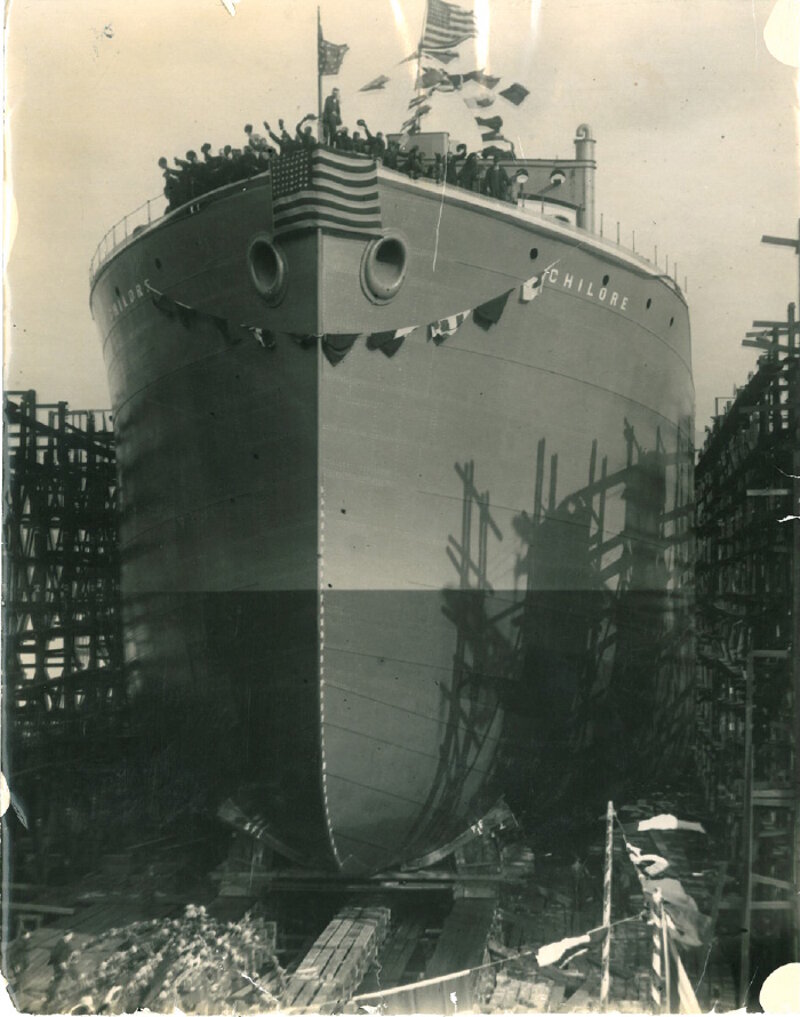

Chilore is launched at the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp. in Alameda, California, in 1922. Photo courtesy of the NOAA Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 299 KB).

As the convoy left Virginia waters, five military vessels formed Escort Group Easy to protect the convoy. The escort included two U.S. Navy ships, two U.S. Coast Guard cutters and a naval vessel that was formerly a British ship.

Convoy KS-520 Ships: J.A. Mowinckel (Flagship), Mount Pera, Bluefields, Zouave, Tustem, Gulf Prince, Robert H. Colley, American Fisher, Para, Mount Helmos, Jupiter, Hardanger, Nicania, Toteco, Clam, Egton, Unicoi, Rhode Island, and Chilore.

Escort Group Easy: USS Ellis, USS McCormick, USS Spry, USCG Triton and USCG Icarus.

Escort Air Support: Scouting Squadron VS-9 out of Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station, North Carolina (Two Navy Kingfisher aircraft).

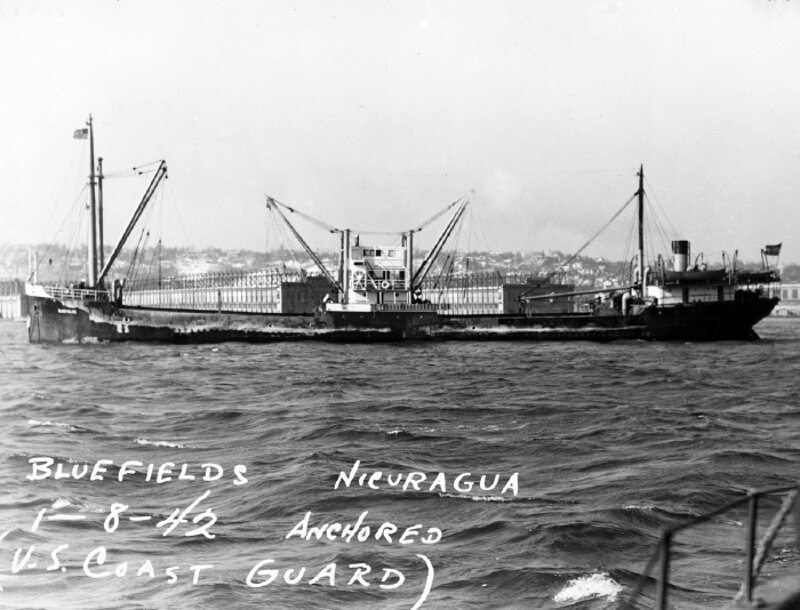

Bluefields as it was configured near the time of the attack. Photo courtesy of NARA. Download larger version (jpg, 325 KB).

Meanwhile, German U-boat U-576 had been operating off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. During its operation, it sustained damage to the #5 ballast tank from an aerial depth charge attack. That day, U-576 reported to U-boat command in France that the damage was severe and irreparable. The next day, as convoy KS-520 set out, the U-boat commander, Kapitänleutnant Hans-Dieter Heinicke, had moved approximately 150 miles offshore to assess damage and attempt repairs.

The historical narrative at this stage becomes a little unclear. Most accounts indicate that U-576 had irreparable damage, plotted a course for France, and simply encountered KS-520 whilst limping homeward unable to resist the target in spite of its damage. What is known is the location where U-576’s final report was made is almost 130 miles east of the KS-520 attack position. U-576 deliberately headed back into its hunting grounds.

U-576 at sea. Photo courtesy of the Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 2.8 MB).

In the afternoon of July 15, 1942, the paths of KS-520 and U-576 intersected off Cape Hatteras. At 4:00 pm, USCG Triton picked up a sonar contact. The Coast Guard crew dropped three depth charges, followed by five more 10 minutes later. It was no use. At 4:20 pm, the first of U-576’s four torpedoes ripped into the convoy. Two torpedoes rocked Chilore, one hit J.A. Mowinckel, and the fourth struck Bluefields amidships on its port side, sinking her in minutes.

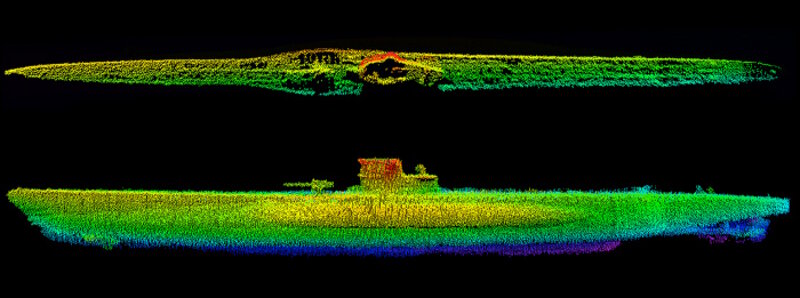

Moments later, U-576, suddenly surfaced in the middle of the convoy. Immediately, the U.S. Navy Armed Guard crew aboard merchant ship Unicoi opened fire and scored a hit. Almost concurrently, two U. S. Navy Kingfisher aircraft straddled the U-576 with depth charges and sent it to the bottom of the sea with all 45 crewmembers. Over the next hour, Escort Group Easy, in concert with patrol aircraft, continued to conduct antisubmarine operations to ensure the U-boat had in fact been sunk.

Sonar image of U-576 wreck site. Photo courtesy of NOAA/SRI. Download larger version (jpg, 672 KB).

Meanwhile, the damaged Mowinckel and Chilore maneuvered inshore to await rescue tug operations. Though seeking safety, they accidently ran straight into the Hatteras minefield. During the salvage attempt, tugboat Keshena struck a mine and sank. Both Chilore and Mowinckel were further damaged by mines. Chilore later sank under tow in the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay where it remains today. J.A. Mowinckel was repaired and returned to service.

In addition to the deaths of the 45 submarine crew members, the skirmish resulted in four Allied casualties. A U.S. Merchant Mariner and a member of the U.S. Navy Armed Guard crew were killed aboard Mowinckel as a result of the torpedo strike, and two additional men were killed aboard Keshena in the aftermath.