By Alanna Casey, Doctoral Candidate - University of Rhode Island

May 26, 2013

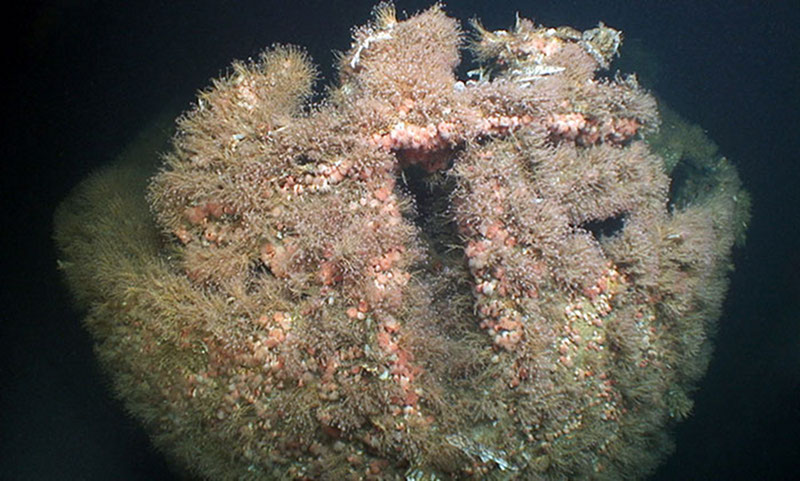

Shipwrecks not only have a historical story to tell, but are also teeming with life. The stern of one of the Billy Mitchell fleet is covered with anemones, hydroids, and catsharks. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 2.2 MB).

From the small boat bouncing in the waves, NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown looked like a still platform unaffected by the troughs and crests. The captain of the small transfer boat pulled alongside the Ron Brown and the scientists and crew of both vessels formed a bucket brigade – passing duffel bags, camera equipment, scientific gear, and computers up to the large research vessel.

One by one, people started climbing from the transfer boat up a wood and rope ladder. As the transfer boat shifted in three dimensions, one scientist on the transfer boat would put on a life jacket, another scientist donning a life jacket would scramble up the ladder with help from the crew of both boats, and a third scientist already on board the large research vessel would throw a life jacket down to the transfer boat in a cyclical pattern.

After everyone was loaded on the research vessel, we had to start the process in reverse, passing luggage, gear, biological samples, and people who had finished their portion of the cruise down the ladder and onto the transfer boat to head back to land.

Once the transfer boat was out of sight on its way back to shore, the ship was finally moving and the second leg of the Pathways to the Abyss cruise had begun!

Graduate students Esprit Saucier, Alanna Casey, and NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research archaeologist Frank Cantelas work with ROV Jason team to survey a World War I era shipwreck. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 5.0 MB).

The remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) Jason and Medea are engineering marvels that allow us to see and collect information and physical samples from waters far deeper than people can dive. Jason’s two manipulator arms are delicately steered by an ROV pilot, who is part of a rotating three-person team that controls the movement of the vehicle, and entire ship, while Jason is in the water. This operation happens in the ROV van.

The van is a small room, housed in a steel truck container, where live streams from Jason's cameras are relayed. The room is lit by 30 computer screens. Each screen shows the image from a camera on Medea or Jason. There are two rows of seats within this "ROV van," three seats up front for the ROV crew with the pilot at the center and the navigator who controls the movement of the entire ship on the right. The next row of seats includes two scientists recording biological and archaeological data, capturing pictures of particularly important features, and making sure a continuous loop of discs record every minute of the dive. The seat on the right side of this second row is for the lead scientist managing the dive. This person directs Jason’s tasks, whether those tasks are archaeological surveys, biological transects, or using Jason's metal arms to take push cores of sediment or carefully place specimens in biological quivers.

NOAA Ship Ron Brown is equipped with a EM122 multibeam echo sounder which bounces acoustic waves off the ocean floor in order to detect anomalies that could be shipwrecks. On board the ship, this equipment sounds like a bird chirping and slowly provides a picture of the seafloor.

The multi-beam is mounted on the hull of the ship and in concert with a spring device that accounts for the movement of the ship, provides accurate distance measurements of seafloor features. Line by line, data showing the relief of the seafloor are detected by the multibeam and they are sent to a large computer screen in a computer laboratory on deck. The lines appear on the screen one by one after the sound wave is released from the instrument, bounced off the bottom, reflected back to the ship and detected.

Depending on the depth of the water and the settings of the multibeam system, each line can take many seconds to appear on the screen. This slow process builds a picture piece by piece, as scientists patiently observe and wait for a complete image. When the multibeam has had enough time to display a complete seafloor feature, analysts and archaeologists measure these features and use their training and experience to identify which shapes in the seafloor are natural and which may represent ship hulls, scour marks, or debris fields.

There are very few places where saying 'doctor' with a question inflection gets a response from almost everyone in the room. An interdisciplinary project of exploration like the Deepwater Canyons cruise brings some of the foremost experts in various academic disciplines and professional paths together in one location. The biologists, ecologists, geologists, and archaeologists on board are all completing challenging and meaningful research while making use of cutting-edge technologies. The ROV engineers maintain and fly one of the world’s most capable ocean exploration vehicles. And the officers, boat engineers, and machinists kept the ship afloat and on course; the chefs worked hard to prepare three amazing meals each day; and artists and writers tirelessly documented every event.

There is no cell phone service miles offshore, Internet access is limited, and no one can stop by the office with a quick question. This combination of knowledge and time is available in few, if any other settings. When all of these experts are working and living together, each meal, hour spent in lab, or walk down the hallway becomes an academic collaboration, informative discussion, or an opportunity to casually learn from experts.

As the cruise comes to an end, I look forward to reading about the analysis of the biological samples, video transects, images, and sediment samples gathered on this cruise. This information will undoubtedly make a huge contribution to our understanding of the natural and human aspects of the deepwater canyons!