By Sandra Brooke, Associate Research Scholar - Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory

May 17, 2013

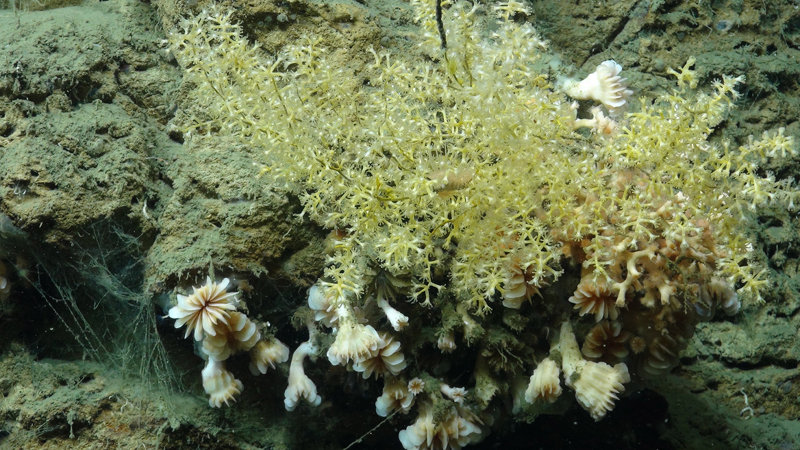

The diversity of coral species on the canyon walls was quite high at times. Here three species grow together on a single outcrop – Desmophyllum (white, bottom), Acanthogorgia (light green), and Solenosmilia (white stony coral just visible at right). Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 6.0 MB).

We first found the coveted Cockscomb coral (Desmophyllum dianthus) at about 700 meters in Baltimore Canyon. These were truly giant specimens, measuring up to 8 centimeters across with thick heavy skeletons. We didn’t find many of these prized species last year, so they were top of the target list during this cruise.

We chose a deep dive site in Norfolk Canyon at about 1,400 meters with a long steep wall, which we thought would be a good place to look for Desmophyllum as well as some deep species of octocoral for our ageing and paleoecology studies.

Cup corals (Desmophyllum) growing around an anemone on a mud-covered ledge Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 6.1 MB).

We landed on a sandy seafloor and made our way to a steep rock face. As it came into view it seemed littered with small dots, which resolved into thousands of little cup corals as far as we could see. They covered the face of the wall, especially on the overhangs, and often appeared in clusters of two or three.

Desmophyllum cup corals can grow clones of themselves, so the members of each cluster were probably all the same genetic individual. Very few of these cups were large, and none matched the giants we found last year. This overwhelming excess of small individuals is curious, and indicates a population that is skewed towards younger recruits rather than older animals. The reason for this is not clear, but in addition to being small, we noticed that many of the cups were dead, indicating either an environmental or biological factor that was causing early mortality in this population.

At this deep site, we also found a species of stony coral called Solenosmilia that we had not seen before in either Norfolk or Baltimore canyon. This is a branching coral, somewhat like Lophelia, that is often found on deep coral reefs but may be a new record for this species in the mid-Atlantic Canyons.

A cross-section view of Desmophyllum, revealing its internal structure. The life history of the cup corals collected will be studied extensively after the expedition. Image courtesy of Liz Baird of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 780 KB).

During several shallower sites we found small isolated clusters of Desmophyllum, but in contrast to the deeper populations, these were generally very large and heavily calcified, but not very abundant. Unfortunately, we do not have time to investigate their distribution further as tomorrow is the last remotely operated vehicle dive for this cruise leg; however, each cup we collected will be put to good use.

The largest specimens were cut in half with a diamond blade then subsampled for studies on cup coral genetics, nutrition, reproduction, age, and growth, and their skeletons will be used as records of past ocean conditions. Some have also been kept alive for research into their environmental tolerances.

All of this data combined will help us understand the factors that influence the distribution of this species, and maybe even solve the mystery of the differences we observed between the deep and shallow populations.