Amy Baco-Taylor: Video Transcript

Hear Amy talk about her job. Download (mp4, 294 MB).

Amy talks about her doctoral research on whale falls in the deep sea and common roles for her while at sea.

Introduction

My name is Amy Baco-Taylor. I'm a visiting investigator at Woods Hole oceanographic institution. I'm a deep sea biologist. I study deep sea corals and I also work on deep sea whale falls. As a researcher at Woods Hole, I'm working on two main projects. One is on deep sea corals and the other is on whale falls in the deep sea, looking at the community that lives on the whale falls. So, I have two kinds of work. One is I do a lot of molecular biology work, which involves a lot of time in the lab; isolating DNA, amplifying DNA, sequencing DNA. The other, I also spend a lot of time looking through the microscope, trying to identify animals collected. Identifying different coral species, identifying the tiny little invertebrates that live on the whale falls.

I did my Ph. D research on whale falls in the deep sea. When a whale dies and sinks to the sea floor, there's a community that develops on it, similar to what you find at hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. They are actually dependant on sulfides that come out of the bones. There are a lot of fats and oils in the whale bones that come out, and bacteria will break them down, and when they break them down, its just like anything that rots, you get this smell, like a rotten egg smell, and that's hydrogen sulfide. And this is the same chemical that comes out of hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, so you get a very similar community on the whale falls.

At sea, I have a lot of responsibilities. Usually, I am one of the Principle Investigators, which means that I have a specific project that I am working on, that I am responsible for, making sure that we get the samples we need to work on that project, making sure the samples are processed correctly, and deciding where we dive, deciding different work that's done. Besides that level, I also do a lot of the, I guess grunt work, actually working on the samples.

The things I really enjoy about working at sea are the people I get to work with. I also just enjoy being at sea. It's just a really different way of life from being on land. You get to get away from all the millions of different things going on at work and just concentrate on one project for a certain period of time. And it's also really neat to get to see all the animals alive, in their natural habitat, and get to look at them in your hand and under the microscope while they're still alive.

Studying deep-sea corals on seamounts where the corals haven’t been affected yet by human activities gives us an idea of that the communities are supposed to look like, so that we can go back and study the impacts on the seamounts that are being affected by humans.

Mission Goals

What we were trying to learn on this expedition was what species of coral were on each of the seamounts, how many species there were, and if the species were the same on each seamount. Also if there were specific depth distributions for each of the species. It’s really important to study these deep sea corals because, in a lot of the parts of the world, people are going and fishing these seamounts, they are going down and trawling, and pretty much scraping everything off of the seamounts and leaving nothing behind. So it’s important to study seamounts in areas where they haven’t been affected yet by fisheries, to get an idea of that the communities are supposed to look like, so that we can go back and study the impacts on the seamounts that are being affected.

The samples we collected on this mission fit into a larger study that I am trying to do; looking at different seamounts at different depths in Alaska and in Hawaii, trying to figure out if there are general patterns of coral distribution. Trying to understand and generalize certain families that live in certain areas, why corals are at the areas they are in. On this mission, we had no idea if we would even find any corals, because nobody had ever dived on these seamounts before. In fact very few seamounts have ever been explored throughout the world’s oceans. We had no idea how many corals we would find or what species, or even how they would be distributed.

On this mission, we were able to collect a number of corals. I think we collected about 150 specimens. We were able to get a sense of which species were abundant on the peaks of the seamounts versus on the slopes and near the base of the seamounts. We collected over 42 different species of corals. So what were doing now is trying to identify all the coral samples that we collected, and that could take a number of years. We are having them identified by people at the Smithsonian institution, and also hope to use molecular methods, sequencing their DNA to help figure out the species identifications. Once we have some idea of what species were seeing, we can compare species lists between different areas and different parts of the world.

Amy gives a first-hand account of what its like to collect coral samples while in a submersible such as the Alvin.

Collecting Coral Samples

In this clip, you see Peter Etnoyer and myself looking at the bathymetry of the seamount that we are about to dive on. This map was put together by Randy Keller and his group. We are trying to decide where the best place would be to dive, and where we think we might find corals, or some of the other invertebrates that we are interested in.

During this expedition, I did five dives in the Alvin. Altogether, I've done 51 dives in submersibles including Alvin, Pisces IV and V, the Johnson Sea Link, and the Turtle. The average dive lasts about 8 hours. We go down right after breakfast and then come up just before dinner. Diving in Alvin is a really unique experience. You get to go down to places where most people will never get to see, and get to see things that few other people will ever get to see. It's very cramped quarters though, in the Alvin. The whole sphere of where the people are is only about 7 feet in diameter, and there is three people in that space with a lot of electrical equipment that keeps the submersible running.

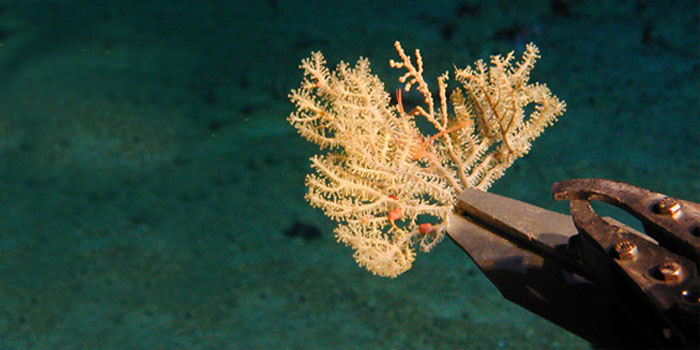

This video shows me getting out of the Alvin after one of our dives on the seamounts. I got to go down and see how the animals are, see how there is different interactions between different species in their natural environment, things that you can't really get a sense with from using trawls. A difference between using submersibles and ROV's is that ROV's aren't really designed for exploration. They are really designed, for example, if you have an experiment on the seafloor, in one place. You can go down with the ROV, and spend a lot of time in that place, longer than you can in a submersible, and collect a lot of samples. Whereas it's not always as easy using an ROV, to go along the seafloor and stop to look at something, and with the submersible, you can go forward, you can stop, you can move along a little ways and say 'I want to go back and check that out again'. It's a lot easier to manipulate. Other ways to sample things in the deep sea include using deep sea trawls which are very non-selective. It's basically just a big net that goes down and scrapes everything off of the bottom. And when you bring it up, you try to sort out all the animals and put them all back together. This method is very destructive, and you can't really get a sense of how these animals were distributed on the seafloor. You know that they all came from that seamount, but you don't know where or necessarily what depth they came from.

This is the sample basket from the Alvin. When the Alvin goes down, we use it to collect pieces of each of the corals that we are looking at in the video, so that we can go back and identify them. And so what it does is it takes either the whole coral colony or a piece of the coral colony and puts it in the basket, in the boxes or the jars on the basket. In this particular image, you can see the particular types of jars inside of one of the boxes. The idea with those is to keep each individual coral sample separate, so we can know where that particular specimen came from, what depth, what exact site. When we go back and describe the species, we would like to know where they came from. So the samples are brought up, and we take all of these sample jars and all of the corals, and we put them into the cold rooms to try to keep them at the temperature at which they lived, to try to keep them alive longer, so that we can process them longer.

Here, I have a sheet of paper in my hand, and while we are in the submersible, we write down what we're collecting and where it was collected from, to correlate to each jar. When we first bring the samples up, you can't always tell looking at a video or looking through the window of the submersible, what family or species a coral is. So when you first bring it up, to make sure you label everything correctly, we look at the corals again, to make sure that we have the identifications right from what we were able to see through the window.

So when we collect the corals from the deep sea, its really hard to get the crews to go and do this kind of research. And so the specimens are very valuable. You never know, down the line, what other types of experiments you might think of to do with them. So we try to preserve the corals. Every single specimen we get, we try to preserve as many different ways as we can. So that's what you see here, is us going through and taking different pieces from each coral, and putting them into different types of tubes, and each of those types of tubes has a different type of preservative, for the different types of experiments we might want to do down the line. The two most important samples are, we put a large piece in Ethanol, which we give to the Smithsonian, which they use to identify what species the coral is, and the next most important sample is we take a small piece and we put it into a freezer that is at -80 degrees Celsius. And that's the reason that we're wearing gloves. This is because we are going to use those samples to look at the DNA of the coral, and we don't want to contaminate the coral with our own DNA.

In this image, you see the mucus coming off of the corals. The bamboo corals in particular, like to produce a lot of snot. We had a group with us on the cruise who looks at the microbial community associated with each of the corals, so they were collecting this slimy mess to take back to their labs and look at the DNA, to figure out which species of microbes were living on the corals.

Return to profile