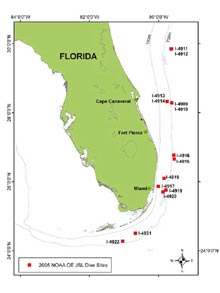

Figure 1: Our Johnson-Sea-Link submersible dive sites during this expedition. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Figure 2: An example of the lushly diverse habitat explored during this expedition. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Florida Coast Deep Corals 2005 Mission Summary

November 20 , 2005

Sandra Brooke, Ph.D.

Principal Investigator

Research Associate

Oregon Institute of Marine Biology

![]() View video footage of the beauty and diversity of the deep-sea coral reefs of Miami Terrace. (Quicktime, 1.1 Mb.)

View video footage of the beauty and diversity of the deep-sea coral reefs of Miami Terrace. (Quicktime, 1.1 Mb.)

It is Saturday night and we are steaming for home, one day earlier than planned since the weather took a turn for the worse, is looking equally bad for tomorrow, and a tropical storm (Gamma) is heading our way. We are on a 12-hour roller coaster ride! It is always disappointing to lose submersible days, especially for those who were scheduled to dive; however, natural phenomena are beyond our control and on the whole we have been very lucky with the weather considering it is November and we are in the Gulf Stream (Figure 1).

During the days that we could not dive, we ran fathometer transects over potential future study sites, so the time was not wasted. Some of the more interesting features were mapped in detail to produce a 3-D bathymetric image. Although we could not dive on all of our sites, we managed several dives within all three of our proposed study regions, and collected video transects, photographs (Figure 2) and many kinds of specimens during all of our dives. Those samples not used for research will be sent as voucher specimens to museums and to our outreach exhibit at the Smithsonian Marine Ecosystem Exhibit in Fort Pierce.

This expedition had a very diverse group of scientists on board, including microbiologists, invertebrate biologists, icthyologists, chemical ecologists, geologists, GIS experts and even someone looking for worms in coral rubble. Nothing that was taken from the sea floor was wasted and we have plenty to keep a ship-load of scientists busy for many months to years! Our cruise has had many highlights, some more significant than others, of course. The greatest was the discovery of a previously unknown 100 ft tall coral mound, covered with a diverse array of invertebrates and large colonies of live coral, more so than any of the other sites. (Figure 3) Several small catsharks were observed swimming around the base of the mound, and our ichthyologist, Dr. Grant Gilmore, suggested that they might be gathering to mate.

In the Northeast Atlantic, around the coasts of Europe, Lophelia coral has several different color variants such as pink, orange or red, as well as the usual white. We had never seen anything other than the white form in this region or the Gulf of Mexico, so it was very exciting to see a bright orange colony during one of our dives. (Figure 4) The color does not appear to be linked to the genes or the gender of the coral. We think that microorganisms living in the coral tissue may cause the (apparently non-pathogenic) color difference.

The coral colonies, sponges and gorgonians (soft corals) can be large and dramatic, but the small creatures that live within and between the tangled coral skeleton are just as interesting and even more diverse. One of our science party, Dr. Jim Thomas, is an expert on small crustaceans called amphipods, and is especially interested in those that live in sponges. He found several kinds of amphipods on deepwater glass sponges and gorgonians, and may have discovered a whole new family and well as one or more new species of amphipod. On our last dive, we visited one of the largest, deepwater sinkholes known in the world, with a depth of 1800 feet. Corals, sponges and their associated creatures grow in abundance along the tops and sheer walls of the hole. The bottom initially appeared to be covered with a thick layer of sediment, but was actually millions of empty shells of pelagic marine gastropods. These animals spend their whole lives in the water column, but when they die, the shells sink to the bottom, where they are usually blown around by currents until they break apart. Those that fell in the deep sinkhole had nowhere to go so these shells have been accumulated over many many years.

Figure 5: Solenosmilia variabilis coral. We believe this is the first record of this coral in this region. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Most of the occupants of the habitats we invade are passive to our presence; they either do nothing, stare blindly at the lights, or hide from us. A few however, such as a feisty swordfish which attacked our submersible, seem to resent our alien intrusion and have no compunction about showing it. He moved too swiftly for our cameras to record other than a very fleeting blur of his attack as he hit the sub strongly enough to give us a good jar and, unfortunately, break off a portion of his sword

We have documented many gorgeous habitats during the cruise, and there are many still out there to be discovered. (Figure 5) The more we learn, the more we realize how very little we know. Although the global threat to deepwater corals increases daily from the expansion of deepwater fisheries, Florida's deep reefs (>200m) habitats are unimpacted, so far. With continuing research and education, they will hopefully remain that way.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.