Figure 1: The deep sea coral Enallopsammia profunda. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Figure 2: A specimen of Keratoisis bamboo coral inside the collection box of the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible, rising to the surface. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Sweat the Small Stuff

November 10 , 2005

Charles G. Messing, Ph.D.

Professor of Oceanography

Oceanographic Center

Nova Southeastern University

![]() View

video footage of a feather star, also known as an unstalked crinoid,

on Lophelia coral. (Quicktime,

684 Kb.)

View

video footage of a feather star, also known as an unstalked crinoid,

on Lophelia coral. (Quicktime,

684 Kb.)

Marine scientists have sampled deep-sea coral reefs off the southeastern United States for many years, but they chiefly used trawls and dredges deployed from surface ships. While this kind of research can tell us something about which creatures live where, it tells us little about how they interact with each other and how they respond to the environment. The Johnson Sea Link submersible allows us to examine the lives of these organisms in much greater detail, even if we only have a few hours at a time to visit their habitats. It’s not a novel analogy, but imagine how little an alien would learn about life on earth if it could not enter our atmosphere but could only drag a net across our planet’s surface.

My particular interests in this expedition are threefold: discovering the range of different kinds of animals that live on deep-sea coral reefs, finding out how they interact with each other, and learning more about how they respond to their physical environment. On my dive yesterday, we ran two major survey lines on a pinnacle off Cape Canaveral—one up the southern slope and one up the northern slope. Our intent was to determine the abundances and distributions of animals along these lines.

A pair of lasers flank the sub’s video camera, projecting a pair of green dots on the sea floor that remain 25 cm apart, whether the sub is one foot or ten feet from the bottom, and whether the camera has zoomed in or out. Pilot Phil Santos’ job was to keep the sub at about the same speed and height above the bottom—no mean feat on the hummocky, irregular and often steep sea floor in a current that reached almost three-quarters of a knot (~36 cm sec-1). After we return, several of us will analyze these videos in detail in order to quantify organism distributions relative to each other and to bottom topography.

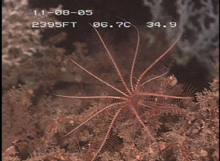

Figure 3. A feather star, also known as an unstalked crinoid. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Figure 3. A feather star, also known as an unstalked crinoid. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Figure 4. Mystery creature: a fuzzy tree-like organism (or its house) on a dead coral branch. Click image for larger view and image credit.

We have also been collecting samples on each dive. While Lophelia pertusa has been the most common reef-building coral so far, we collected another species—Enallopsammia profunda—at the base of the northern slope (Figures 1 and 2). While the large creatures, stony corals, bamboo corals and sponges are obvious and relatively easy to deal with, I am also interested in the smaller organisms that live on and among the coral branches. For example, we have found several species of feather stars (unstalked crinoids) (Figure 3) and brittle stars that cling to coral branches, and two species of sea anemones, one short and pink, one slender and purple, that appear to live only in the skeletal cups, or calices, of dead corals. A carnivorous worm (family Eunicidae) builds a tough cartilaginous tube for itself along a coral branch, and the coral responds by expanding its skeleton, creating a thick, rigid limestone wall around the worm’s tube, further protecting it.

One of our observations, however, remains a mystery. The dead coral branches are usually covered by huge numbers of tiny fuzzy “trees” only a few millimeters high. Their thicker bottom branches are hollow tubes and they appear to be constructed of very fine mud grains. One possibility is that they have been built by a diverse and abundant group of usually microscopic amoeba-like creatures called foraminifers. Here’s a photo (Figure 4), if anyone out there has an idea what they might be. Just remember, they may look like seaweed, but they were collected at a depth of over 2400 feet, where there is no light for photosynthesis.

Florida Coast Deep Corals will be sending daily reports from Nov 7 - 21. Please check back frequently for additional logs from this expedition.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.