Lara Miles of TDI Brooks logs the mountain of data collected daily during the Lophelia II expedition. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Watching the work underwater from the lab on the big screen. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Ewing Bank Here We Come!

September 8, 2009

Lori Johnston

Robert F. Westrick

C & C Technologies, Inc.

Sheli Smith, PhD

PAST Foundation

![]() Watch a video showing the Ewing Banks wreck at 621 meters (2,036 feet) deep.

Watch a video showing the Ewing Banks wreck at 621 meters (2,036 feet) deep.

The days and nights begin to run together and we quickly lose track of time. The date and specific time mean nothing out at sea. We are conscious only of the tasks that must be completed and times when we are responsible for being on shift; all else falls to the wayside. Sleep is overrated, and even meals don’t mean much. Sam, the cook, always makes sure we have something to snack on. His cake-like chocolate chip cookies didn’t last long, and his coconut oatmeal cookies performed a similar vanishing act. However, because it is so easy to miss meals, coffee and sandwiches can be breakfast, lunch, or dinner. It is a different world out here, almost uninterrupted by the rest of the world, but the presence of oil rigs and today’s technology keep us in touch.

The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason submerged at 23:55 GMT and headed below. Today’s dive is on the Ewing Banks wreck, a peaceful, yet poignant wreck, virtually a shell of her former self. The ship’s shape is clearly delineated by the remnant copper sheathing and keel centerline that runs the length of the vessel. Jason landed close to the wreck and with the line art image Rob provided projected on the navigation screen, we can see where the ROV is in relationship to the wreck at all times. We can even see what Medea is up to.

One of the tasks, asked of us by Dan Warren back at C & C Technologies, is to examine the damage to the stern and try and determine how it happened. A small piece of netting sitting on the bottom at the stern is suspected as the culprit, but we need to determine if it is historic or modern net. So with our shopping list of things to examine we got to work. Unlike both previous wrecks, the lack of artifacts on this one makes identifying the shipwreck more difficult. But we figure maybe something will lead us in the right direction so we slowly tour the wreck site looking for clues. Marking up our map with times and pieces of observed information we are able to flesh out our plan for when we return to the Virtual Van after the biological transects and collection.

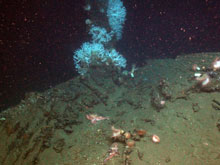

Ewing Bank has a spectacular colony of Lophelia on the stempost, so Erik and Peter were eager to photograph and collect samples. They plan, through photographic comparison over time, to accurately measure the growth rate of the coral. Everyone oooh’d and ahhh'd over the spectacular imagery of the thicket of Lophelia produced by the Aquapix camera, which we have dubbed as "The Beast." Throughout the evening, Peter collected and photographed the biota (flora and fauna), while Amanda Demopolous of the U.S. Geological Survey collected soft, core samples from the seafloor around the wreck to determine the types of benthic (bottom dwelling) organisms at this site. Cheryl oversaw the collection of small coral samples for genetic testing. Ultimately, all the data will be compared with the growing database of biota and genetic information for the Gulf. Lori successfully deployed another long term "pagoda" to collect etched data regarding microorganisms on the wreck over time.

It was just one of those days. No catastrophe, but just a compounding of little things gone awry — the Beast slid off its tray and had to be retrieved, we lost the sharp little knife for cutting the net before we got a chance to use it, and the annoyance of the rubberized fingers of the starboard arm sticking together so that the fingers had difficulty opening. And then there was the saga of the giant rusticle. By the time we returned to the van, the operation was two hours behind schedule. So, our list of tasks had to be streamlined with no time for wandering, lingering or really wondering. It was just get in and do the tasks.

We decided to combine photography and collection activities, starting in the stern. We got some great shots of the snapped pintle that once attached to the rudder. We took some "Best of" video of the stern neatly laid open behind the hull, and then we went in for the sample of net. What we planned as a short little retrieval thwarted us at every turn. Finally, with a small piece recovered, Bob tried to get it in one of the awaiting quivers. The pesky little sample had the audacity to float. Ah ha! We’ll use the slurp and suck the sample into an awaiting canister. The fingers of the arm would not release! Finally, after much under-the-breath Popeye-type commentary, the piece was retrieved answering the question about the damage in the stern. It appears that a modern net caught the sternpost, knocking it over and dragging the stern structure with it.

Moving forward, we photographed and cleaned off a piece of ceramic that turned out to be a cup or bowl. An entire shelf of ceramics still sits along the portside of the hull in the stern, most likely the remnants of the pantry. Fragments of bowls, cups, and plates lie atop the shelf. We zeroed in on the one piece that had fallen down but retained a complete base, looking for a maker's mark that could lead us to a date for the shipwreck. With precision, Bob retrieved the ceramic fragment and safely tucked it into a side-tray bio box.

We headed up the hull toward the bow, examining the centerline for evidence of a keelson and looking for ballast. We are hoping that ballast will shed some light on the last voyage of the vessel by pointing to the last port of call where the ship loaded ballast into the bottom of the hull for stability. Sheli, convinced there was only wood amid ships, bet Rob we wouldn’t find ballast. The bet was agreed upon, and then foolishly Sheli pointed out a round object that — sure enough — turned out to be a large ballast stone, costing her the bet. Drat!

In the bow, the photography went smoothly, capturing what looks like cant frames and the remnants of the lowest breast hook. Finally, we were ready for recovery of a huge, magnificent rusticle — the last task our time allotted. Lori, who had been patiently waiting in the back of the van, sprung into action.

A magnificent rusticle hangs off the stempost, waiting for us to sample. Click image for larger view and image credit.

We recovered a bowl or large cup fragment from the concentration of ceramics in the stern. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The rusticle, beautiful and majestic as it hung sentinel-like at the bow stem, was collected into the scoop. The rusticle was about 4 inches across and about 9 inches long, a really great sample, but very delicate. It is often difficult to get such an intact sample back to surface; this dive proved to be no exception. Ben, the ROV pilot, successfully gathered the sample into the diamond shaped basket and moved into position for storage. The lid was open, the box ready to accommodate the beauty. Gently, he tipped the basket forward and we all gasped as it slid off of the scoop, past the box, bounced off a quiver and dropped past the ROV onto the seabed. Backing up, we were amazed to find it lying intact.

Ben switched with Bob, and he went in for retrieval. Gentling the tube with the basket, Bob rolled the tube into the basket, and then out the other side. The ROV watch changed and Matt arrived. He put the basket scoop away and activated the arm. Honestly, we all looked at each other, and there was no need for words. That tube was toast! But when you are an expert with tools, there are no limits to what you can do.

Matt gently slid the fingers of the arm around the fragile rusticle and picked it up just like he was picking up an egg. Slowly he rotated the arm toward the side tray to store the specimen. Then, without warning, the fragile walls of the rusticle collapsed, leaving only a plume of red rust spiraling into the water column as dancing clouds of red dust.

Lori took it well; there was no wailing or outright tears. Undeterred, Matt returned to the bottom with the arm and collected the shell fragments for Lori, safely storing them in the quiver before heading back to the surface. While smaller pieces were recovered, it is hard to forget the “one that got away”.

So, onward and upward. Jason popped out of the water at about 8:45 a.m., and the Ron Brown began steaming to the next site. Now we have time to rest, before we hit the lab and begin making sense of all the data collected then prepare for the next site. The Ewing Ban flight was a good lesson in preparation and patience, ensuring that we will be prepared for the next longest dive. While the mystery of the Ewing Banks wreck remains, we must move onto the next site, which brings some excitement to the scientists, giving a boost to the overall atmosphere in the labs.