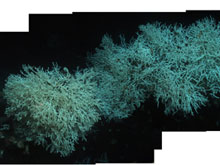

The deck railing of the Gulf Penn provides a perfect perch for the Lophelia colonies growing abundantly along the shipwreck. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The Gulf Penn Wreck

September 10, 2009

Lori Johnston

Robert F. Westrick

C & C Technologies, Inc.

Sheli Smith, PhD

PAST Foundation

We made it to the last of the wrecks, the Gulf Penn. Our time at sea has been short but really interesting on a personal as well as a professional level. Most of the scientists on board are new to the archaeological and microbiological examinations executed on this expedition. It has been fascinating to learn about these areas of study, and how the wreck interplays between disciplines.

The Gulf Penn is a particularly interesting wreck from a biological point of view. As a tanker that was sunk by a German U-boat during WWII, it has become a large reef for a variety of corals, particularly Lophelia. At a depth of 552 meters (1,713 feet), there are spectacular colonies of Lophelia that run down the vessel's handrails, looking like a thick forest of frost-covered trees. These bright white corals have congregated in immense numbers all over the wreck, making this site one of the top areas for Lophelia populations in the Gulf. The biologists on board have been anxiously waiting for the opportunity to image this site.

Analyzing Lophelia Growth

Stephanie Lessard-Pilon, a grad student from Penn State, spent hours in the Zen Van imaging the Lophelia. Stephanie enthusiastically photographs her chosen colonies with careful accuracy and in minute detail. It is currently estimated that Lophelia growth occurs at approximately 3 cm (1 inch) per year, but through these studies that estimate may dramatically change. Images from 2004 first identified the Gulf Penn as valuable site for Lophelia study. Shipwrecks offer a great platform for scientific study, as there is an accurate record of when the ship sank, therefore giving a timeline for growth.

The Gulf Penn wreck also allows specific site studies, such as around the davits, handrails, and other superstructure. The ship davits, in particular, supply a site that a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) is able to view from numerous angles, and can be repeated each visit to the site. This becomes vital for Stephanie’s research on the growth rates of the wreck coral. Steph would gleefully record and excitedly analyze each image as they were being taken. You could just tell by the ring in her voice that at that moment in time, nothing else was important but the rush of doing her research.

A Passion for Coral Taxonomy

Peter Etnoyer, a coral taxonomy specialist and photography enthusiast, passionately describes the large colonies of Lophelia pertusa. He comments on how they colonize only certain areas of the wreck, possibly where current, nutrient loading, and dissolved gases are most abundant, as well as where sedimentation is limited. Another coral, the gorgonian (sea fans and sea whips), can be seen, but with a much different size and form than is normally found within the Gulf. This "Great Gorgonian" tends to be more sheet like, hanging off of the rails. Peter theorizes that the Lophelia have out-competed the gorgonians for space on the Gulf Penn, but further research is needed.

Peter explains how Lophelia has been found in reefs as large as two kilometers throughout the North Atlantic. However, Lophelia colonies generally do not grow that large in the Gulf of Mexico. Until recently, biologists had not found large rolling fields or swales of Lophelia in the Gulf. Today, the Gulf Penn represents one of the largest known concentrations.

Peter has been doing the biological transects for the wreck portion of the ROV Jason dives. This involves running the ROV at a particular heading down the length of the vessel and noting the biological distribution. This is done in multiple lines and in uniform distances from the main superstructure. The transects are particularly important in the demonstration of what is commonly known as the reef effect, where the shipwreck actually acts as an artificial reef for biological growth and activity.

Genetic Diversity of Lophelia

In 2004, Cheryl Morrison of the U.S. Geological Survey received six samples of Lophelia from the Gulf Penn site. As a genetic specialist, Cheryl is looking at the genetic diversity of the Lophelia throughout the Gulf. With only a limited number of samples, including 11 more from this dive, Cheryl hopes to determine the genetic diversity and be able to match it to natural sites surrounding the wreck. The Viosca Knoll and Gulf Penn represent the two closest wrecks to natural sites in this part of the Gulf, but they will also assist in determining which are the parent colonies as opposed to clone colonies. This differentiation becomes important for the management and protection of the Lophelia, but also to mitigate any possible danger to the survival of the colonies.

There is a strong sense of the importance of these samples with Cheryl. The determination of how the Gulf currents move and seed the Gulf is little understood. It was thought that the currents of the Gulf moved from west to east, reaching up from the Yucatan, into the Gulf and out past the Florida Straits, but research has hinted that the late fall eddies that spin off from the Gulf current play a major role in the dispersion of the Lophelia populations. To test these theories, current meters and sediment traps have been set up on a number of natural sites.

A Multidisciplinary Journey

The hours tick by and our time on the Gulf Penn is soon up; Jason is headed to the surface. The long hours of sample gathering and careful analysis of images have left a glazed look on many of the biologists' tired faces. They all seem giddy with what they were able to accomplish over this short time on site. If there was any doubt that the wrecks portion of the expedition was valuable, it was confirmed by Cheryl; she commented that “…the Gulf Penn acts as the perfect site — what could be better than a structure 60 feet off of the sea floor, right in the middle of nutrient rich currents for the Lophelia to grow?” The multidisciplinary aspects of this journey really shine when biologists, geologists and archeologists can all find common ground in a sunken vessel.