A Wonderland of Exotic Critters and Underwater Volcanos

July 31, 2002

Bill Chadwick, Geologist

Vents Program, Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, NOAA

Since our last report, we have made three more dives with ROPOS at Explorer Ridge. The ROV is running well and the weather has been good, so we have been able to spend a lot of time on the bottom with only brief intervals between dives. It's been exhausting, but richly rewarding. Dive R667 explored some sites away from Magic Mountain within the area surveyed by ABE on the last leg. It documented the complex interaction of volcanism and tectonism on this ridge segment.

The ROPOS manipulator arm holds a sample of an inactive chimney in which “Fossilized” tubeworms are embedded, an extremely rare find. Click image for larger view.

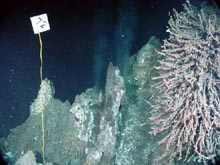

This huge chimney structure (~15 meters tall, a small portion of which is shown in this image) is venting fluid at 312 degrees C, the highest temperature to date in the Magic Mountain area. Marker 72 was placed by ROPOS to make it easier to find on subsequent visits. Click image for larger view.

Dive R668 made a traverse across the ridge and sampled sulfide chimneys of various ages and compositions for a study of how these structures form and break down over time. One particular sample of an old inactive vent was found to have “Fossilized” tubeworms embedded in the chimney.

Dive R669 was focused on sampling vent fluids from the many additional chimneys we have found recently in the Magic Mountain vent field. Amazingly, we keep discovering new vent chimneys on every dive. Within the Magic Mountain area, we have mapped out four major clusters of vents, each with 10 to 20 individual chimneys. But in addition, we often come across isolated chimneys scattered between the main clusters. The number of vents and the volume of hot water being expelled in this area is really remarkable.

The interesting part for us is that the vents are so diverse. For example, mid-way through dive R669 we found a new chimney that was taller (15 m) and hotter (312 C) than any we had seen so far. Also, it was the first black smoker we have seen here. All the other active chimneys we have seen have been venting clear, intensely shimmering fluid. We are exploring a true submarine volcanic wonderland.

This octopus was spotted on the side of a fault scarp during a geologic traverse. Click image for larger view.

From the Seafloor to the Lab

Kimberly Williams

Teacher at Sea

In the last few days, the views from the bottom have been spectacular. We were given a special treat during one geological exploration dive when we witnessed an interaction between a spider crab and an octopus on the edge of a steep scarp. We sampled at many new vents and vent fields, with such exotic names as Majesteuse (French for Majestic), Merlin's Mound, and Easter Island. Each area is full of traits that make it unique and special. At the Zooarium, for example, we saw an amazing number of sea spiders—a deep-sea, Indiana Jones nightmare!

After ROPOS came up from the dive and was secured, there was the usual swarm of activity on the deck that resembled a procession of ants carrying the contents of a picnic back to their colony. I allowed myself to get swept up in the steady stream of scientists and samples that flowed from the deck back to the lab area. When I approached the biology lab where the biologists and ecologists work, there was already a crowd around the microscope. I looked at this black, fuzzy, tubular matter on the stage and felt a little guilty that I wasn't nearly as fascinated as everyone else in the room. But as I waited in line for my turn to look and I listened to everyone describing the amazing purple goo on the black tubes, I became curious. When it was finally my turn to look through the microscope, I realized why they were so excited. Close up, I could see tiny purple colonial organisms that were beautiful! But what were they? No one knew their name, but the consensus was that they were some type of polychaete worm that we had not yet seen on this expedition. Even one of our resident microtaxonomy gurus couldn't identify them. Well, I guess we'll just have to wait until we reach the shore before their secret identity will be revealed.

Julius and Amanda analyze samples in the ship's biology lab, immediately after ROPOS returns to the deck. Click image for larger view.

One of the graduate students from the University of Manitoba, Julius Csotonyi, explained to me why he was so excited about the beautiful and mysterious purple goo that we just saw under the scope. He pointed out that many bacteria found in the upper water column are pigmented. Rather than being present for my viewing pleasure, the pigment is actually used by the bacteria to convert the sunlight into energy that the bacteria can use (like plants do). The big excitement for him then is trying to figure out if the brilliant purple we see really is coming from photosynthetic pigments, and also trying to imagine why bacteria living thousands of meters away from the light of the sun would need to contain the pigments that process light. They never see light! Or do they? Is it possible that the heat from the vent can actually make the area glow with light that can be used by the bacteria to obtain energy? No one knows, but that is what Julius is trying to find out!

Buccionid whelks (the large ivory-colored gastropods) are probably using their siphons to deposit feed. Snails, limpets and polychaete worms are also visible, as well as a blue/purple mat which is yet to be identified. Click image for larger view.

You might think that was really just enough excitement for me for one day, but wait, there's more! Working right next to the beautiful purple goo of unknown origin was another scientist who shared with me her explorations into the exciting world of gastropods, the most abundant animal found on vents and, quite conveniently, marine life that was big enough to see with my own eyes! When this graduate student, Amanda Bates from the University of Victoria, finished explaining the finer points of snail and limpet feeding behavior, I was feeling some "gastric" emotions of my own. It turns out that limpets have almost as many feeding strategies as we have in our high school cafeteria. Amanda was excited because she had verified for the first time ever that aside from grazing and having symbionts, limpets can suspension feed, a special technique of filtering food out of their surroundings (imagine yourself capturing candy bars that float by while you're in a swimming pool). Amanda thinks that having the ability to consume food in different ways and also being the biggest gastropod on the vents gives the limpets a distinct feeding advantage over the two species of snails in the region. She'd really love to study the concept of competition for resources among the three species, but will have to come up with an experimental design that can be used on location. As of yet, no one has ever performed such an experiment. These are the kinds of questions that are driving Amanda's curiosity about the animals that make a living in the extreme environment at seafloor hot springs.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.