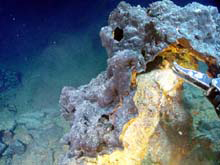

The ROPOS manipulator arm prepares to sample an inactive chimney. The yellow color is caused by the alteration of iron-rich minerals, and the black outer crust is primarily manganese. This image was taken by the new underwater high-resolution digital camera on ROPOS. Click image for larger view.

A Whole New World

July 26, 2002

Bill Chadwick

Geologist, Vents Program

Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, NOAA

Our first ROPOS dive at Explorer Ridge, dive R664, gave us the first glimpse of the bottom in more than 18 years, and the opportunity to try out new imaging technology on the ROV. Also, it gave us the chance to follow the clues that were collected on the first leg of this year's Submarine Ring of Fire expedition. The first leg found evidence of hydrothermal plumes above the ridge. One of our main goals on this second leg is to find the sources of these plumes on the seafloor with ROPOS.

We got a good start during our first dive. Once on the bottom, we initially passed through an extensive field of inactive sulfide chimneys, evidence of past episodes of hydrothermal venting in this area. We were also able to use a new start-of-the-art digital camera that is on ROPOS for the first time. This camera is a 5-megapixel handheld model that was never intended for use at the bottom of the ocean. It took six months of development by the Canadian Scientific Submersible Facility (who operate ROPOS), in collaboration with Deep Sea Power and Light, to create a complex interface to control the camera remotely and the pressure housings for the camera and PC controller.

These animals at the top of the chimney are deep-sea octocorals or soft corals (Octocorallia: Alcyonacea), and sometimes go by the common name “mushroom coral.” As with other cnidarians, the mushroom coral has stinging cells or nematocysts within its flashy tentacles that are used to capture minute prey. Click image for larger view.

The first images captured by this digital camera are beautifully clear and colorful, and we are already looking forward to using this new tool on future dives.

After several hours on the bottom, we came across our first active hydrothermal chimney, out of which hot water was gushing. We had found what we were looking for! Unfortunately, right after this, the dive had to be aborted because of worsening weather. We had probably reached the edge of the Magic Mountain vent area, whose location is not yet exactly known.

When ROPOS gets back in the water for its next dive, one of the primary goals will be to map out the extent of this major vent field and to sample the hot spring fluids that are pouring out of the seafloor. And of course, we hope to fill the new underwater digital camera with striking images of what we find.

A Wild Ride at Magic Mountain

Kimberly Williams

Teacher at Sea

During ROPOS's first dive at Explorer Ridge, scientists crowd the control room to catch their first glimpse of Magic Mountain vent field. Click image for larger view.

We reached Explorer Ridge and everyone on the ship was anxious to begin. The new science personnel barely had time to get their sea legs and become acquainted with the ship's safety procedures before the excitement started. Our first dive was at Magic Mountain, which is a hydrothermal vent that was discovered in 1984 but has not been explored since. Once we were positioned over the Magic Mountain area and ROPOS was deployed, the computer room was “standing room only.” Everyone wanted to get a glimpse—the first glimpse for most of us—of this barely charted territory. The expedition had really begun!

An unusual jellyfish swims by ROPOS during its first dive at Explorer Ridge. Click image for larger view.

Our first dive at Explorer Ridge didn't disappoint us! It was breathtaking! We saw amazing mineral formations, gorgeous benthic creatures, and were even treated to a sideshow by a lonely jellyfish. Some of the chimneys we saw were so large that they didn't fit in the camera's view. There were a few amazing formations that we lingered over for a while that looked like they had golden honey pouring out of them. Chemical oceanographer Dr. David Butterfield explained that this pretty yellow color was probably caused by iron oxides or oxyhydroxides (basically rust). I was surprised at all the different colors that decorated this site—fiery brilliant reds, pale sky blues, deep emerald greens, and that amazing golden yellow. No matter where I went on the ship, every monitor that had a feed to ROPOS's cameras was tuned in to the “Magic Mountain Show.” Scientists and crew alike gathered around the screens to marvel at its beauty. Then, like a ride on a roller coaster, it ended long before I was done enjoying it. The wind had kicked up, the seas were building, and we had to pull ROPOS back on deck. The chief scientist, Dr. Bob Embley and the ROPOS engineers decided to try again in a few hours.

Now you might think that we were all moping around with nothing to do, but that wasn't the case. This was disappointing, but once again, this frugal bunch found a way to take advantage of every single moment of ship time. Even though the weather was too rough for ROPOS, there were other operations we could run on deck that would still provide important information about the region. We used the time to collect samples with a rock corer and to run a series of CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, and Density) casts to test the water at different depths in this area for evidence of hydrothermal plumes.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.