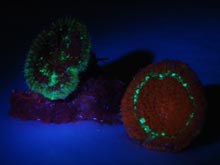

Montastrea cavernosa exhibiting both orange and green fluorescence in the mouth of the polyps. These corals are found everywhere, from shallow to deep water. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Montastrea cavernosa exhibiting green fluorescence only. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Coral Fluorescence

May 24, 2007

Michael Lesser

University of New Hampshire

![]()

![]() Fluorescent coral at 150-foot (45.7-meter) target-depth sample collection dive.

(Quicktime, 2.6 Mb.)

Fluorescent coral at 150-foot (45.7-meter) target-depth sample collection dive.

(Quicktime, 2.6 Mb.)

![]() Fluorescent coral samples back in the lab.

(Quicktime, 13.3 Mb.)

Fluorescent coral samples back in the lab.

(Quicktime, 13.3 Mb.)

One of the reasons that so many people enjoy diving under clear blue seas to study — or even just to look at — coral reefs is the sheer amount of diversity.

Coral reefs harbor more species of organisms than do tropical rain forests, and we haven’t yet described all the species on a coral reef. Additionally, shallow coral reefs reveal a dazzling array of colors that marine biologists have been trying to understand for decades. Why be colorful? What is responsible for the colors that the human eye perceives? In many cases, the color we see is caused by the reflectance of colors not absorbed by the organism when sunlight shines upon them. In many instances, certain types of pigments are responsible. It's the same as when you look at the green color of a leaf on a tree: you see green because it is the portion of the visible light spectrum (violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, red) not absorbed, and therefore reflected, by the pigments responsible for photosynthesis.

Many marine organisms are doing exactly the same thing. But another phenomenon, called fluorescence, also occurs on coral reefs, and this process has been of increasing interest to scientists for a number of reasons. Fluorescence occurs when certain compounds (e.g., pigments, proteins) absorb light of one wavelength and fluoresce light at a longer, different-color wavelength. Basically, the compound fluorescing absorbs light of a shorter wavelength (e.g., blue) and becomes “excited” into a higher energy state. When that energy state is relaxed light is emitted, but at a longer, less energetic wavelength (such as green, orange, or red) than when excited with blue light.

Many species of corals, which make-up a considerable amount of the hard structure of coral reefs, contain proteins that fluoresce when exposed to blue light. These proteins are produced by the corals themselves, are extremely resistant to degradation, and result in a dazzling array of colors (see figures). These proteins have now been isolated and produced in many laboratories around the world; they are currently an important tool in the study of the molecular biology of cells, because they can be used to visualize cellular processes that have never been previously observed.

The question now being addressed by marine scientists is why fluoresce at all? Many ideas have been suggested, including that these compounds absorb harmful wavelengths of light (e.g., ultraviolet radiation) and dissipate that energy as harmless visible radiation, or prevent the damage that could be caused by the production of harmful compounds (e.g., reactive oxygen species). Some have hypothesized that the fluoresced light can be used for photosynthesis by the symbiotic zooxanthellae that live in the coral, and others have suggested that it may be a signal used by the corals to tell potential predators, “I taste terrible, don’t even think about eating me!” The technical term for this is "aposematic coloration." We are working on these interesting questions, and a lot remains to be discovered about this interesting phenomenon.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.