The Challenge of the Deep

May 17, 2004

Mary Grady

Adjunct Earth Science Instructor

Northeastern University

Diana Payne

Biologist and Education Coordinator

Connecticut Sea Grant

The difficulties which attend the inquiry add to the zest of the research . . .

—E. Forbes, 1859

Late last night, Hercules broke its previous depth record, on its way down to Kelvin Seamount. But around midnight, when it reached the sea floor at 4,000-m depth, it was immediately clear that all was not going well.

IFE ROV pilot Todd Gregory and IFE chief bosun Mark DeRoche work on the manipulator arm. Click image for larger view.

"The manipulator arm was evidently not working," Dr. Peter Auster said this morning. "And some of the foam flotation had cracked, so the vehicle lost its neutral buoyancy. Now it was negatively buoyant, and the only way to keep it off the sea floor was to run the thrusters. That just kicks up sediment and

we can't get good video, so there was no point in even trying to stay down there."

It took about an hour for the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) operators to stabilize the equipment and begin the ascent. The science team got a brief look around from the landing site. "We saw a few spiky little corals, a couple of fish, some sponges," Dr. Les Watling said. "But we didn't really get to see much."

It had taken about four hours to reach the 4,000-m depth; it took another four hours to bring Argus and Hercules back on deck. The engineers immediately set to work on the problems. They drained and checked the hydraulic system, and they discussed how to address the problems with the foam flotation blocks. Part of the answer was to remove some of the ballast from Hercules, so it could maintain neutral buoyancy with less foam.

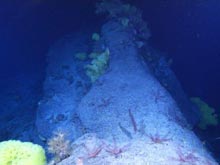

Stegosaurus Ridge with crinoids, bright yellow sponges, and various corals. Click image for larger view.

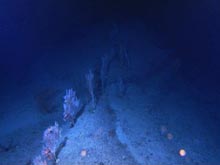

Stegosaurus Ridge on Manning Seamount, with pink sea fans lining up to face the current. Click image for larger view.

While the engineers worked on the ROVs, more multibeam data was acquired. The scientists kept busy in the lab, and caught up on email via the ship's satellite link. The education team broadcast its first live program ![]() on the Internet. Since Hercules was on deck, the Webcast was unable to show live video from the sea floor. The team improvised with a highlights tape and live voice-over by scientists Dr. Jon Moore and Dr. Scott France. They showed video of an unusual geological formation they explored two nights before at Manning Seamount. Informally designated "Stegosaurus Ridge," the basalt dome has a long, rounded ridge line and steep smooth sides, with tall sea fan corals distributed across the top. The abundance and distribution of sea stars, corals, and sponges along the ridge made for a diverse landscape and colorful images.

on the Internet. Since Hercules was on deck, the Webcast was unable to show live video from the sea floor. The team improvised with a highlights tape and live voice-over by scientists Dr. Jon Moore and Dr. Scott France. They showed video of an unusual geological formation they explored two nights before at Manning Seamount. Informally designated "Stegosaurus Ridge," the basalt dome has a long, rounded ridge line and steep smooth sides, with tall sea fan corals distributed across the top. The abundance and distribution of sea stars, corals, and sponges along the ridge made for a diverse landscape and colorful images.

Ivar Babb of NURC UCONN, Tolland High School teacher Lance Arnold, and Sea Grant education coordinator Diana Payne, review their script for the Webcast. Click image for larger view.

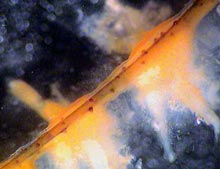

On its deep dive, Hercules carried dozens of Styrofoam cups to demonstrate the effects of water pressure. The brightly colored cups had been decorated by school children, teachers at workshops prior to the cruise, crew members, and their friends. The cups were collected in a mesh bag and tied to Argus for the trip to the sea floor. The education crew also attached a decorated Styrofoam wig head to the Hercules frame. It returned compressed to about one-sixth its original size!

The decorated Styrofoam wig head was attached to Hercules on its way down to the sea floor. Note the size of the wig head relative to the gauges on the right.

The decorated Styrofoam wig head compressed at 4,000-m depth. Compare the size of the compressed wig head to its original size!

By this evening, the seas were building and the sky was filling with clouds. We were heading west as a low-pressure system was heading east, so we were hoping that the weather wouldn’t get too rough. Hercules was expected to go on its next dive on Kelvin sometime around 10 pm.

Black Corals

Scott C. France, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Biology

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Co-Principal Investigator—Mountains in the Sea

Unlike the other corals we are studying on this expedition, black corals are not octocorals. These polyps have only six tentacles surrounding the mouth, whereas octocorals have eight tentacles. Black coral polyps are very small. The colony Dr. France is holding in front of the ROV Hercules in the May 12 Log had over 100,000 polyps!

Black corals belong to the order Antipatharia, which translates to “against disease.” It was once thought that properties of the skeleton could ward off various illnesses. Although black corals are usually reddish brown or white, their skeleton is black. These corals are also known as thorny corals, a reference to the spines that cover the skeleton. The skeleton of black corals is a dense combination of hardened proteins (used to make jewelry). Black coral polyps can produce copious amounts of mucus when stressed, possibly as a defense against predators.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.