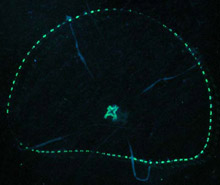

Top portion of a tubeworm from the Brine Pool, photographed with white light (above), and with blue light to stimulate fluorescence (below). Click image for larger view

Fluorescence Exploration

August 10, 2004

Charles H. Mazel, PhD

Principal Research Scientist

Physical Sciences Inc.

Mikhail V. Matz, PhD

Research Assistant Professor

University of Florida

![]() Click here to see a sea spider caught on video using blue lights.

Click here to see a sea spider caught on video using blue lights.

Yesterday, we dove at the Brine Pool, searching for fluorescence on the bottom. Scientists on previous dives had collected samples of tubeworms, mussels, shrimp, and sediment from the site. We had looked at them for fluorescence in a dark (and cold!) room on the ship, so we had an idea of what to expect. The tubeworms and mussels had a pale yellow fluorescence, and there were spots of orange fluorescence in the sediment sample, apparently due to traces of oil.

After outfitting the submarine for the first fluorescence dive, Charlie Mazel entered the forward sphere. Eran Fuchs occupied rear chamber. The team descended with all the lights off, enjoying the bioluminescent show on the way down. On the bottom at 650 m (2,140 ft), they had their first look at the Brine Pool -- appearing like a small black lake in a desert of muddy sea floor, and ringed with tubeworms, mussels, shrimps, crabs, fish, and more.

To make fluorescent observations, the Johnson-Sea-Link is modified by placing blue filters on the submersible’s two 400W HMI lamps. Click image for larger view and further details.

After enjoying the scenery, the team turned on the blue lights and set off in search of fluorescing animals. (Read more on detecting fluorescence.) Within a few minutes, we noticed a bright green fluorescing spot on the bottom. When the spot moved, it became apparent that it was attached to a small shrimp, which resisted capture. The glow seemed to originate from a spot at or near the eye, but this was hard to determine from inside the sphere.

Mike Matz and Jörg Wiedenmann made the second fluorescence dive. They traveled over the Brine Pool, the mussel beds along its shores, patches of tubeworms, and the surrounding sediments. They observed the pale fluorescence of tubeworms and mussel shells that had been seen in the laboratory, but not much else. They collected an anemone that didn’t look fluorescent on the sea floor, but with more careful examination on the surface revealed some interesting fluorescent structures.

Between the two submersible dives, a team led by Sönke Johnsen conducted blue-water scuba diving and collected near-surface jellyfish, ctenophores, and salps. After dinner, the fluorescence team examined these in the dark and found beautiful fluorescence in some of them. The samples were measured, photographed, and preserved for later identification of the fluorescing pigments.

Jellyfish photographed with white light (above), and with blue light to stimulate fluorescence (below). Click image for larger view

Exploration is just that, and you can always find something unexpected. New discoveries await us at the other planned dive locations -- all with very different types of bottom communities.