Surveying a Tropical Paradise

November 5, 2002

Catalina Martinez

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

Jeremy Weirich

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

During the past week, we have surveyed the boundaries of several banks and submerged reefs, as well as a few islands. Two submerged survey sites include Maro Reef and Pioneer Bank. With the exception of a few coral blocks exposed at low tide at Maro Reef, neither site has emergent land associated with its reef system. Both regions encompass large coral reef areas with a diversity of corals and fishes, and the extensive open coral atoll of Maro Reef is the largest coral reef area in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI).

The islands surveyed this week include Gardner Pinnacles, Laysan Island, and Lisianski Island. Gardner Pinnacles is a series of basalt sea stacks surrounded by steeply sloping shelves and several shallow pinnacles (say that 10 times fast!). Although Gardner has the smallest land area of all NWHI, it is known to be highly diverse and abundant with fish.

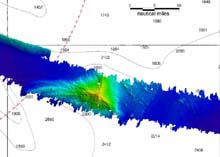

The rainbow image is a digital terrain model of a seamount, producing a three-dimensional interpretation of the ocean feature. Click image for larger view.

Laysan Island is often referred to as the Gem of the Leewards, and, at approximately one mile in width and about one-and-a-half miles in length, is the second largest island in the NWHI chain (Rauzon, 2001). With a large hypersaline lake at its center and approximately 700 acres of fringing reef, this unique oasis is home to more than 2 million breeding seabirds representing 17 different species, as well as Hawaiian monk seals, green sea turtles, and a great diversity of marine life.

As we pass Laysan Island, we see what appears to be a desolate sand spit with a few remaining palm trees, along with a few white tents that are home to two researchers who have been living on the island for four months. Although this barren island still teems with life, it is a mere shadow of a once thriving ecosystem that was destroyed in the early 19th century predominantly by guano miners, feather hunters, and rabbit and mice depredations (Rauzon, 2001). Many endemic bird and plant species are known to have perished as a result. And because of the lack of documentation, we have no way of knowing just how many others disappeared.

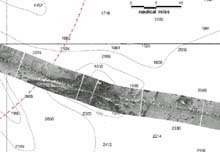

A backscatter mosaic, which records the strength of the sonar return from the ocean floor, is displayed with the chart in the background. Click image for larger view.

Similar fates befelled Lisianski Island, which is approximately half the size of Laysan with a 40-foot sand dune on the northeast portion of the island. Lisianski Island is associated with a large reef system called Neva Shoal to the southeast. As a result, a very rich marine environment surrounds the island.

The surveys around the islands and banks continue to yield high-resolution images of features that have never been observed in such detail. These areas, which appear as nothing more than vague blue blobs on a chart, are actually outlined with sheer ledges, dramatic slopes and carved walls. The most interesting features, however, appear while transiting from one site to the next. Undiscovered seamounts, some in the shape of relatively steep spires, rise up from the deep, revealing the ocean floor's true identity.

Two accompanying charted images depict a seamount located southwest of Gardner Pinnacles. The rainbow image is a digital terrain model connecting thousands of soundings to produce a three-dimensional interpretation of the bottom. The gray image is a backscatter mosaic recording the strength of the sonar return off the same seamount. Darker images indicate a strong return, such as bare rock, while whiter images are where the sonar beam has been partially absorbed by softer sediments.

“The bathymetry data gives us quantitative depths,” describes Paul Johnson, a University of Hawaii scientist and resident multibeam system specialist on board the R/V Kilo Moana. “However, the backscatter imagery provides textual information, such as the type of bottom composition. We can determine the morphology of the features we come across, and have a better idea if they're old seamounts or recent hotspots just from the intensity of the sonar return.”

Even at sea, holidays are sometimes celebrated, so the folks on the R/V Kilo Moana take a moment to have some fun at Halloween.

Along with all the mapping and data crunching during the past week, we also took time to celebrate Halloween. Chief Steward Debby Gall prepared some very special Halloween cakes, and members of the science team carved a jack-o-lantern. Debby was prepared for the festivities, and provided glow sticks for the lantern, which was placed on the starboard bow after dark. Several people on board dressed up in costume for the day, and goody bags filled with candy were passed out to everyone on board. The only things missing were the trick-o-treaters.

Although both research and ship crew work very hard while at sea, many take the time to view the spectacular sunsets and even a few sunrises during the course of a cruise. On this cruise, we have been fortunate to have good weather conditions and some magical sunsets.

References

Maragos, J. and Gulko, D. (eds.) 2002. Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: Interim Results Emphasizing the 2000 Surveys. Honolulu: US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources. 46 pp.

Rauzon, M.J. 2001. Isles of Refuge: Wildlife and History of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. 205 pp.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.