By Michael Cheadle - University of Wyoming

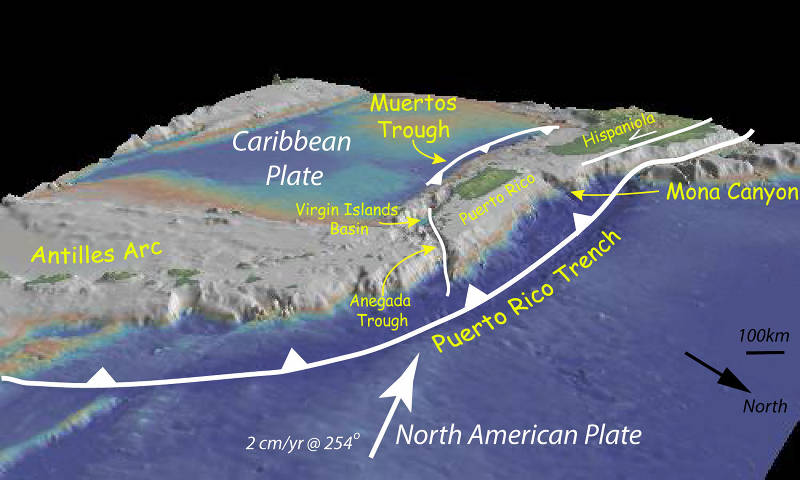

Figure 1. Bathymetry of the northeast corner of the Caribbean Plate showing the major faults and plate boundaries; view looking south-west. The main bathymetric features of this area include: the Lesser Antilles volcanic arc; the old inactive volcanic arc of the Greater Antilles (Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola); the Muertos Trough; and the Puerto Rico Trench formed at the plate boundary zone between the Caribbean and obliquely subducting North American Plates. Vertical exaggeration is 5:1. Bathymetry data generated using the Global Multi-Resolution Topography (GMRT) synthesis in GeoMapApp . Download larger version (jpg, 391 KB).

The island of Puerto Rico lies in a dynamic plate-boundary zone between two tectonic plates: the North American plate and the northeast corner of the Caribbean plate (Figure 1). The region is very seismically active with an average of five earthquakes (including aftershocks) with a magnitude greater than 1.5 occurring near Puerto Rico every day during the last 12 months (March 2014-March 2015). Although the vast majority of these earthquakes are too small to be felt by people, these earthquakes provide evidence that the North American plate is moving westward relative to the Caribbean plate at about two centimeters/year.

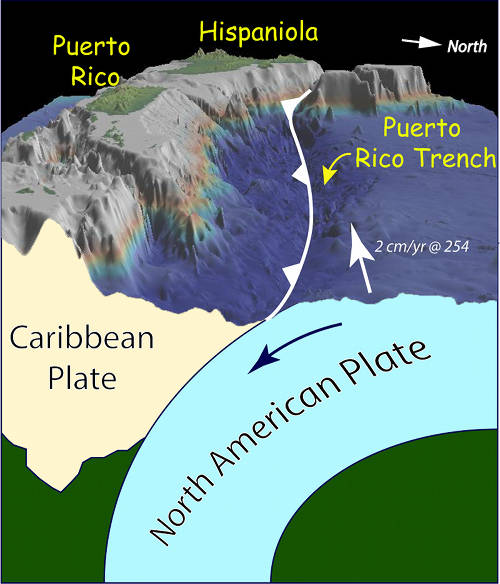

Figure 2. Cross section view looking west showing how the Puerto Rico Trench forms between the obliquely subducting North American Plate and the overriding Caribbean Plate. Bathymetry data generated using the Global Multi-Resolution Topography (GMRT) synthesis in GeoMapApp. Download larger version (jpg, 772 KB).

The northern boundary of the Caribbean plate is sub-parallel to the relative direction of motion of the two plates, so that the plates mostly slide past each other. However, the motion is slightly oblique to the plate boundary (see the arrow in Figure 1) and the North American plate is partially converging with the Caribbean plate and being obliquely subducted beneath Puerto Rico (Figure 2).

In contrast, the eastern boundary of the Caribbean is approximately perpendicular to the relative motion of the North American plate (Figure 1) and so here, the North American plate is being pushed down beneath the Caribbean plate and subducted into the mantle, creating the active volcanic island arc of the Lesser Antilles.

Puerto Rico itself is a now-extinct volcanic island-arc terrane which started to grow approximately 190 million years ago. The island began life as an active volcano, formed by melting of the mantle as the Pacific plate subducted below the west coast of South America at about the present-day latitude of the Peru-Ecuador border. Beginning approximately 80 million years ago, the island-arc was rafted northward and then eastward as the North and South American plates pushed westward around the newly forming Caribbean plate .

These older volcanic rocks are overlain by younger (less than 30 million years old) carbonates and other sedimentary rocks. The carbonate rocks extend off the north shore pf Puerto Rico as a gently dipping platform that forms the southern end of the Puerto Rico Trench (Figure 1).

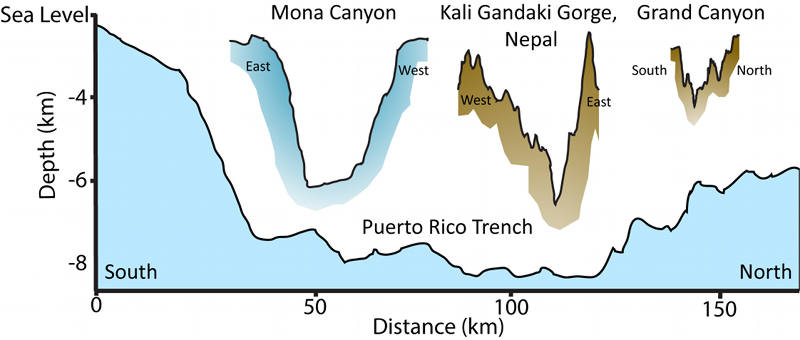

Figure 3. How big is the Puerto Rico Trench? Cross sections, all drawn to the same scale, across two canyons found on the continents: the Kali Gandaki Gorge in Nepal and the Grand Canyon in Arizona, and across the Mona Canyon from the west of Puerto Rico, to compare with the Puerto Rico Trench. Vertical exaggeration is 10:1 to fit the sections onto the webpage. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 349 KB).

The northern boundary of Puerto Rico is marked by the 800-kilometer-long Puerto Rico Trench, which is the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, with a maximum depth of 8,648 meters (Figure 1). It is the eighth deepest trench in the world and the deepest seafloor outside the Pacific Ocean. The trench was formed by the oblique convergence as the North American Plate pushed down beneath the Caribbean Plate.

Figure 3 shows a north-south section across the Puerto Rico Trench drawn at the same scale as three other deep canyons to emphasize its enormous size: the Mona Canyon, which lies just to the south of the Puerto Rico Trench (Figures 1 and 4); the Kali Gandaki Gorge in Nepal, one of the deepest gorges found on the continents; and the well-known Grand Canyon in Arizona.

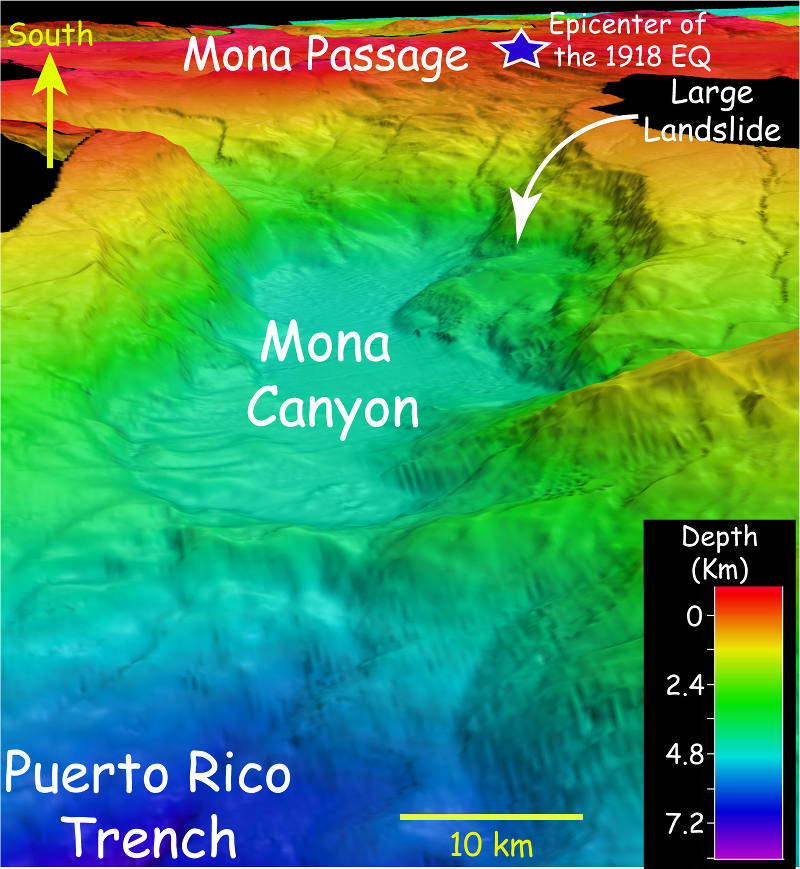

Figure 4. View of the Mona Canyon looking south towards the Mona Passage. Blue star shows the epicenter of the 1918 San Fermin magnitude 7.5 earthquake. Vertical exaggeration is 2:1. This bathymetry data is representative of the data collected during the first two legs of this expedition. Data courtesy of USGS and the Ocean Exploration Trust. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Puerto Rico is bounded on the south by the Muertos Trough, on the west by the Mona Canyon, and on the east by the Virgin Islands Basin (Figure 1). The Muertos Trough is an elongated basin developed where the Earth’s crust to the south of Puerto Rico is thrust under the Muertos fold-and-thrust belt, which lies to the south of the island. Mona Canyon (Figure 4) is an approximately north-south trending canyon which is almost 30 kilometers across, formed by east-west rifting.

The epicenter of the 1918 San Fermin magnitude 7.5 earthquake is located just to the north of the Canyon and the earthquake was likely caused by faulting related to this rifting. This earthquake triggered a six-meter high tsunami wave that swept along the west coast of Puerto Rico and may have generated the large landslide shown in Figure 4.

Lastly, the Virgin Islands Basin is an extensional basin which lies at the south-western end of the Anegada Trough, a feature that was explored in 2013 and 2014 by the E/V Nautilus. Together the Muertos Trough, the Mona Canyon, the Virgin Islands Basin/Anegada Trough, and the Puerto Rico Trench, define the margins of the Puerto Rico-Virgin Islands microplate, a small coherent block trapped between the larger Caribbean and North American plates.

During the course of Leg 3 of Océano Profundo 2015: Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs, all of these major trenches and canyons will be explored by Okeanos Explorer using the remotely operated vehicle, Deep Discoverer.