WHOI R/V Atlantis survey technician Dave Simms discusses the acquisition of bathymetry data with UCONN NURC Director Ivar Babb and NOAA survey technician Nick Forfinski. Photo by M. Crosby. Click image for larger view.

Strange Miracles

July 12, 2003

Diana Payne

Connecticut Sea Grant

To me the sea is a continual miracle;

The fishes that swim - the rocks - the motion of the waves - the ships, the men in them,

What stranger miracles are there?

Walt Whitman, Miracles

Twenty-four hours after departure, some members of the science team are still working on getting their sea legs. The cold front from yesterday remains, determined to remind us that one cannot, as Plutarch notes, “mitigate the billows or calm the winds.” The constant slam of waves against the hull of the ship kept many in “the pit” —the berthing area below the main deck—awake. Those in staterooms on the 3rd level mentioned difficulty even staying in their bunks!

The weather decks have been secured, which means that no one can venture out to enjoy the warmer air surface (and sea) temperatures of the Gulf Stream. Crossing into Gulf Stream waters at this time of year, we do not see a change in water color—that occurs only in the fall. A rise in water temperature was detected yesterday afternoon, indicating that we had indeed entered Gulf Stream waters.

The morning began with a science team meeting in the ship’s library. For the first time, all members of the Mountains in the Sea science team gather with Chief Scientist Dr. Les Watling to discuss the mission plan and science objectives. There are several co-principal investigators and collaborators involved in this cruise, and Dr.Watling is responsible for ensuring that science objectives are met for all collaborators involved. The science objectives include sampling to study biodiversity relating to invertebrate and fish community structure; and deep-sea coral molecular genetics, reproductive structure morphology (shape), feeding strategies, aging and taxonomy. Although the geological and physical oceanography of New England seamounts have been studied, we know little about the animals that live there.

Deep-sea corals are not new to science. Forbes and Agassiz studied these animals in the 1800s. Deep-sea corals were included in drawings on the voyage of the HMS Challenger, and were also published in 1954 by Roy Waldo Miner in his Field Book of Seashore Life. Dr. Watling describes the recent interest in deep-sea corals as more of a rediscovery.

Deep-sea corals appear to share similarities with shallow-water corals, including reproductive strategies and general body structure. One major difference between the shallow and deep-water corals, however, is their feeding strategy. Most shallow water corals use algal symbionts to make food by photosynthesis, but deep water corals rely on food particles in passing water currents. Think of it as standing atop a mountain and waiting for your food to blow by, and you can’t jump up and grab it!

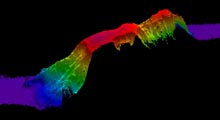

Partial bathymetry data for the Kelvin seamount. Image by N. Forfinski. Click image for larger view.

Additional science activities are discussed during the meeting. A series of 10-minute rock dredge samples will be added to the evening schedule to sample the biodiversity of organisms in seamount sediments. Organisms will be preserved for future study and identification. To obtain rock dredge samples of sediment on the summit of a seamount, a length of cable must be deployed which is long enough to reach the depth.

In the case of most seamount samples on this expedition, we will need approximately 3,000 meters of cable for a sample at 1,500m, or a 2:1 ratio. If this cable is deployed at a rate of 50 meters per minute, it will take one hour to reach the sample site. Recovering the sample will take a similar amount of time, meaning that a single rock dredge sampling event will take more than two hours to complete. One hour to deploy, a few minutes to be sure the sample gear is in place, ten minutes to sample, a few minutes to assess if a sample has been collected, and one hour for recovery. Recall that this is only sampling at the TOP, or summit, of the seamount!

Afternoon activities include a SeaBeam mapping of Kelvin seamount. Members of the science party gathered to watch as the colorful image began to appear on a computer screen. Data from this map will allow the science team to determine likely dive sites on Kelvin. Once the SeaBeam mapping is complete, we will continue to steam toward Manning seamount, the first dive site. Those diving in DSV Alvin attend an orientation with Alvin pilots. Many of the scientists diving in Alvin have beards … and have been instructed to “trim” the beloved facial hair to ensure a tight fit of the emergency breathing apparatus used on Alvin.

Weather reports for tomorrow predict calm seas. This is welcome news to many still feeling a bit queasy, and even better news for Dr. Les Watling and Dr. Scott France, who are scheduled to dive tomorrow morning. We shall have to wait and see what strange and miraculous things they bring back from Manning seamount.

First Impressions

July 12, 2003

Pasquale Frisketti

Teacher

Hamden High School, CT

“The wonders of the sea are as marvelous as the glories of the heavens…”

Matthew Fountain Maury

Physical Geography of the Sea

Arriving on board the day before departure, we used that time to organize equipment, stow gear and to get acquainted, but it was not the buzz of activity I expected. I was struck by the informality of the science staff. Of course everyone was very dedicated to their objectives, but in a very at-ease manner. The crew members were efficiently going about their business of preparing the vessel for departure, and I heard the previous day had been a whirlwind of furious preparatory activity, due to the short time the ship was in port.

I was caught off guard by everyone’s ease, and had to consciously stop myself and return to the stern of the ship, where I gazed at the DSV Alvin in its sheltered hanger. Here I was, standing in front of the vessel I had read about in numerous National Geographic articles since I was in high school, and had viewed in so many television documentaries.

Researchers Ivar Babb, Dr. Peter Auster, and Dr. Jon Moore, (left to right) discuss upcoming dives with Alvin in the background. Click image for larger view.

I have a hard time “jumping up and down” about things, but this expedition was a major check on my “to do” list, and one I never expected to be involved in. Some might consider this odd, that being on-board Atlantis would be such an adventure. You might hear whispered, “You mean you didn’t get to dive in Alvin?” Well, it is important to realize just how few people get the chance to do that. Consider the amount of training and expertise required to make this highly advanced bit of technology available and accessible for research use, let alone the cost of $39,000 a day for using the R/V Atlantis, and you begin to realize how little time is available for dives. For a teacher, yes, just being on board and involved in this project with all of its extended networks is fascinating and exciting. And, oh yes, the ease did give way to a hectic level of activity. Once we left the dock, the action really started.

It was exciting to watch the on-board operations unfold after many months of planning. The many different program component groups, including scientific personnel, crew technicians, dive coordinators, and educators gathered in various small meetings to discuss specifics about expectations, objectives and schedules, and the pace of activity increased. As more of the logistics were agreed on, the groups began to coordinate their various activities.

After witnessing the incredible effort, coordination, and compromise it took to plan and prepare for this multidisciplinary deep sea expedition, it now entered a more organic phase, taking on a life of its own. There is always a very dedicated schedule, but what might actually occur is often subject to change. Concerns mainly focus on the weather and conditions of the sea. Factors that may only be minor considerations during a landside operation are pivotal in decision making here. We all keep our fingers crossed for fair skies and calm seas.

I have been impressed by several things only hours into this adventure. One is the multidisciplined nature of the personnel gathered together. There are researchers involved with several specific aspects of deep-water corals. Some are concerned with feeding adaptations, some with reproductive capabilities and dispersal mechanisms, and some with DNA identification of the species of the corals. Others are investigating deep-water fish and squid, and still others are concerned with the geologic mapping through multibeam sonar of the seamount sites. Water conditions will be closely monitored, as will the compendium of all aspects of the seamount ecology. Also, there are investigators not on board for which specimens are being collected to aid in collaborative work. With all these diverse specializations, these researchers coalesce into a productive and cohesive working unit. The primary goal is that everyone achieve as much as possible.

Another impressive aspect is the amazing array of technology that helps the team undertake this project. These will be discussed in detail as the expedition proceeds.