Looking at the Sea

July 18, 2003

Dr. Peter Auster University of Connecticut

Diana Payne

Connecticut Sea Grant

The land may vary more;

But wherever the truth may be-

The water comes ashore,

And people look at the sea.

They cannot look out far,

They cannot look in deep,

But when was that ever a bar

To any watch they keep?

- Robert Frost, from Neither Out Far Nor In Deep

The last full day on the water for 2003 Mountains in the Sea expedition was filled with highlights – from high-tech to a time-honored tradition……

This morning’s DSV Alvin dive included a satellite call with students participating in the SSEA (Sound Summer Exploring Aquaculture) program at the Sound School in New Haven, Connecticut. Alvin Pilot Bruce Strickrott and observers Dr. Peter Auster and Mercer Brugler answered questions from the students 250 miles away, from a depth of 1300m at Bear Seamount!

The biodiversity assessment continued today with two short dives on Bear. When asked about his research, Dr. Peter Auster explains his interest in studying the fish communities of seamounts: “One of the reasons I like to study these areas is because there is a lack of fundamental information that exists about them. They are rarely, if ever, visited and have, for the most part, been undisturbed by human activity. They essentially represent fully functional marine communities when compared to areas closer to shore.”

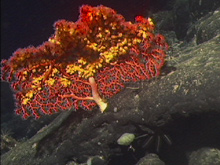

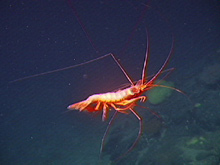

For Dr. Auster, this cruise was eye opening in that it showed how individual fishes are distributed over seamounts - but only in the relatively small areas sampled by the submersible. The fish seen are counted and the habitat quantified in an attempt to understand how populations and communities are distributed within the underwater landscape, and to determine how fish diversity is linked to particular landscape features. It is also important to identify the behaviors of fishes and learn how they make a living within different types of habitats. For example, foraging behaviors can vary depending on the combination of current and bottom complexity. This is particularly interesting around the seamounts, because of the unique nature of the habitats, and because the seamounts often consist of many habitat, or landscape, types.

The physical nature of seamounts affects a variety of factors, including current flow, bottom type, and slope angle, to influence where fishes occur. In observing differences between Manning, Kelvin and Bear seamounts, Dr. Auster notes that fish abundance and diversity are subject to different oceanographic circulation patterns that deliver fish eggs and larvae. This has led to some new questions: How might the interaction of larger scale oceanographic properties and seafloor landscape features influence how fish are distributed on seamounts? How do foraging behaviors vary in relation to these factors? Does predation pressure influence foraging and shelter-seeking behaviors?

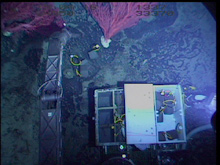

The Alvin manipulator arm deploying basalt blocks (yellow straps) for a coral recruitment experiment. Click image for larger view.

Research like this is done almost entirely visually. Submersibles are often used for areas with high numbers of fishes. An ROV (remotely operated vehicle) might be deployed when conducting long transects to determine species diversity and density. “There is a whole suite of tools available to us - it all depends on what you can do with the resources you have,” noted Dr. Auster. “There is always a trade off. Do you go in a manned submersible with three people and all the video cameras and collection equipment that stay on the bottom for 7 hours? Or, is the best choice an ROV with just the one camera but can cover 3-5 kilometers and stay down for 24 hours or more?”

Diving in an occupied submersible allows scientists to really appreciate the actual landscape and how images on the videos fit into the overall geographic nature of the area. However, ROVs clearly have their place in this type of research. Using a submersible in an area first gives you the ability to better interpret the two-dimensional images collected with the ROV, and using such vehicles allows multiple scientists and students to participate in every dive. Blending these resources to work together is the challenge. And there is never enough dive time!

Investigations of this nature make you aware of the complexities of the deep sea ecosystem. Animals are not just randomly dispersed in the environment; associations of species to different landscape types seem to be relevant. We gain an appreciation of the scope of work that must be done to understand the patterns and processes relevant to maintaining biological diversity of these areas, and the need to do it quickly, before these regions are disturbed by expanding human activities.

Alvin Expedition Leader, Dudley Foster, in the top lab of R/V Atlantis. Click image for larger view.

Interview with Dudley Foster

Expedition Leader/Senior Alvin Pilot

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Ocean Explorer: Could you please describe your role as Expedition Leader.

Dudley Foster: I am responsible for the coordination of the Alvin operations group. It is also necessary to interact closely with the science group to ensure that their dive objectives are met and to keep in tight communication with the rest of the ship since almost everyone is involved during dive operations. If there are problems, the technicians need information to know how to address them. The science group must understand what alternatives are possible. Keeping all things running smoothly between all those involved in Alvin's operation is imperative.

Ocean Explorer: I would imagine safety is the primary concern while Alvin is on a dive. What other issues must you contend with?

Dudley Foster: While the sub is on the bottom, the pilot is in control. We maintain communication from up here in the Top Lab. Our main concern is the weather. The dive schedule is subject to revision dependent upon changing weather conditions. We must also be aware of any ship traffic in the area especially during an ascent. We will then request they stay clear of the dive area. Other than that, concerns center on mechanical operations on Atlantis that might affect Alvin dives. This could be anything from ship propulsion to the “A” frame operation, anything that would impact the recovery of the sub and the safety of the people in the water.

Ocean Explorer: What type of training is involved in becoming an Alvin pilot?

Dudley Foster: To start, we hire people with an engineering background and some real world experience. We are looking for people with a proper level of maturity and responsibility, those that have a high degree of initiative. There is a great deal of self-study involved as well as on the job training. They will initially focus on their engineering specialty, whether it be electrical, mechanical, or electronics, in relation to the Alvin’s systems, as they learn all the pre- and post- dive operations.

Ocean Explorer: There is a very comprehensive checklist sequence that is followed during Alvin dives. How extensive is this?

Dudley Foster: The Alvin preparation is very prescribed, there are 25 pages of pre- and post-dive check sheets and these are rigorously followed, but everyone knows them so well it appears pretty seamless.

Ocean Explorer: How long does the training usually take?

Dudley Foster: The PIT or Pilots in Training Program depends on the individual, as short as a year and a half, up to three years. There are a series of assessments along the way. As they become familiar with each of the systems, the more senior members of the team check them out. Then of course, there is the scientific review. They must have a good sense of what the scientists want, and how to navigate on the bottom to get to specific station locations. They have to pass the engineering board, and eventually they must pass a Navy review. The Navy owns Alvin so the same people that qualify military submarine operators assess the pilots. They are then qualified to take observers on dives on their own. From then on they continue to improve their sampling technique and submarine handling skills.

Ocean Explorer: What advice would you offer a student considering entering this kind of oceanographic research?

Dudley Foster: Be sure to get a good education. I never dreamed that I would wind up doing anything like this. When you’re young, you usually don’t think that way. But I did the homework. That is important, it establishes your discipline. Then I followed the natural progression from high school to college. What enables you to have a choice about where you will be is a good general education. Take that education seriously. Don’t just look at high school as a place to spend your time, and don’t waste that time. We like to hire college graduates; college is a voluntary choice. If you have the initiative to graduate you have a lot of the discipline it takes to get a job done unsupervised, and that’s the key.

Ocean Explorer: What is your favorite part of being involved in this field?

Dudley Foster: The scientific variety. The mechanics of the submersible operation are all very sophisticated, but it also becomes pretty routine with repetition. The variety of the different scientists and disciplines we encounter is very exciting. I have a basic interest in science so I like to learn about the investigations. I also like the challenge of helping the researchers meet their objectives. Science moves ahead slowly, it progresses in baby steps. It may take only several weeks to gather the data, but the scientists are working on the analysis for several years. It could take years to make sense of it, to understand it all.

Ocean Explorer: Would you share one of your most memorable moments about Alvin and deep-sea oceanography?

Dudley Foster: I would have to say coming across the first hydrothermal vents and black smokers. This was a physical phenomenon that was really inconceivable. By that time I had been on quite a few dives already, but coming across those and realizing these things were 200 to 300 degrees C or more was amazing. A few years before we had found low temperature vents, those were the baby steps. Several years later we realized what was going on - that the hot vents were supporting these amazing organisms never seen before in these unbelievable habitats through chemosynthesis.

Ocean Explorer: I describe this to my students and try to impress upon them how this discovery has required us to revise our understanding of so many things.

Dudley Foster: This discovery, that life could exist in a completely new and different ecosystem has changed the way we think about geology, physical oceanography, chemistry and biology, and so much more in these locations. The traditional thinking was that life was limited; it was too hot or too toxic; too cold or too dry. We now know that it is not excluded from these places, that life can exist and thrive there. This has lead to expanding our search for life to places like Europa, the moon of Jupiter, under a frozen ice sheet in a possibly geologically active sea, using tools we are now developing and testing in our deep sea environments.

Interview by Pasquale Frisketti of Ocean Explorer.