Welcome to the deep ocean. Commonly considered to be the waters below 200 meters (656 feet), the deep ocean is a place where it is dark, food is scarce, and temperatures and pressures are extreme. Life is hard here, but there’s a lot of it.

There’s no place like home, but what does home look like for creatures of the deep? The variety of habitats in the deep ocean is extraordinary. These habitats are radically different from those anywhere else on Earth, and they’re host to organisms that have adapted to survive harsh conditions that are unimaginable to those of us on land.

Seamounts and canyons, deep-sea corals and sponges, chemosynthetic features like hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, and the water column are just some examples of the features — both geological and biological — that provide habitat for the deep ocean’s wildly wonderful life forms.

In June 2024, in recognition of National Ocean Month and World Ocean Day, we shared information about these habitats and some of the creatures that call them home. Read on to learn more.

Habitat

Simply, the place or environment where a particular organism lives.

Seamounts and Canyons

While much of the seafloor is a flat, muddy plain, it’s interrupted by dramatic geological features: seamounts and submarine canyons. Similar to and often rivaling their counterparts on land, these seamounts and canyons are among the most important features in the ocean. That’s because they provide habitat for seafloor and water column organisms that scientists have found to be more diverse and abundant than most of the habitats that surround them.

Hard rocky habitats in areas of high current are often areas of high biodiversity. In this scene from the Gulf of Alaska’s Surveyor Seamount, a red rockfish swims over basalt boulders covered in encrusting sponges and other invertebrates, including a bright orange anemone and two large, pink nudibranchs. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download largest version (jpg, 7.8 MB).

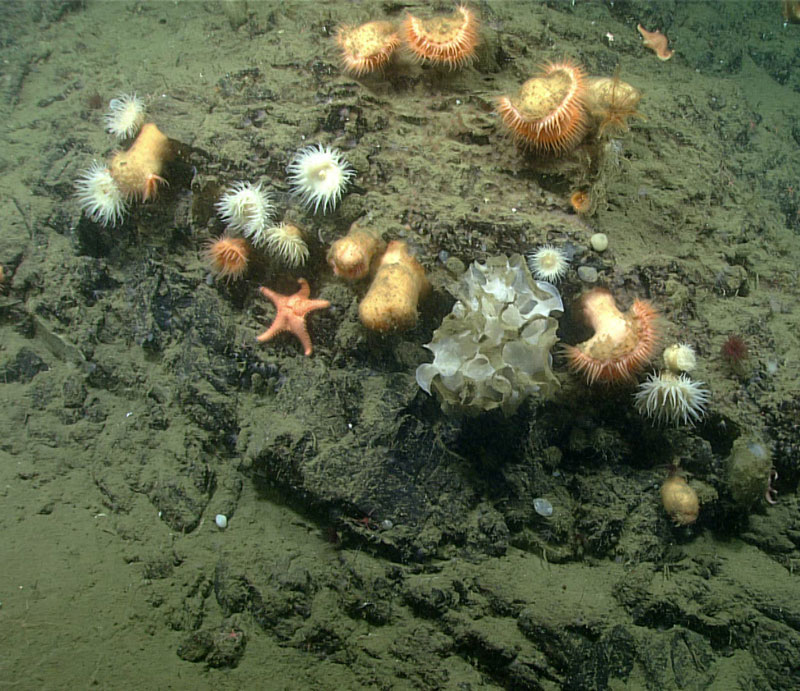

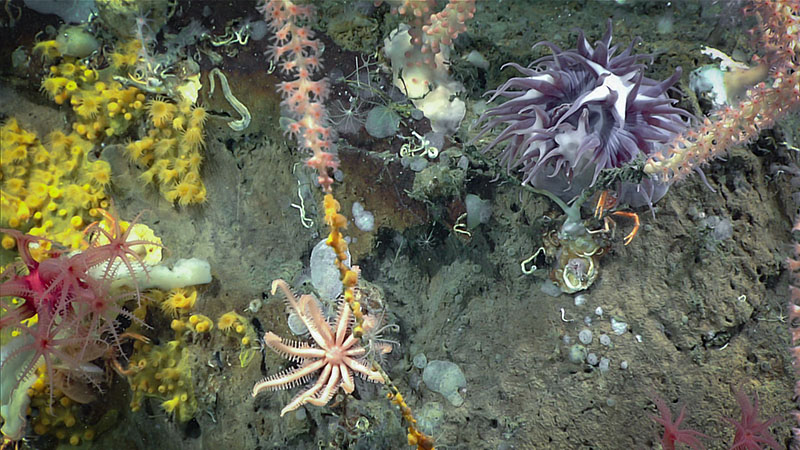

Canyons like Canada’s Gully Canyon link the shallower waters of the continental shelf to the deep sea, funneling sediment and organic carbon (food!) to deeper waters and creating potentially good habitat for a variety of animals, including corals, sponges, anemones, sea stars, and squat lobsters, as seen here. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Deep Connections 2019. Download largest version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Seamounts are underwater mountains that rise at least 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) above the seafloor. Most are remnants of extinct, underwater volcanoes. Some are active volcanoes. Seamounts can be found in every ocean basin and are typically on the edges of tectonic plates or in chains of seamounts formed by mid-plate hotspots (e.g., the Hawaiian Islands).

Submarine canyons are steep-sided underwater valleys that range in size and shape. Located on continental margins throughout the global ocean, these canyons connect the continental shelf with the deep ocean.

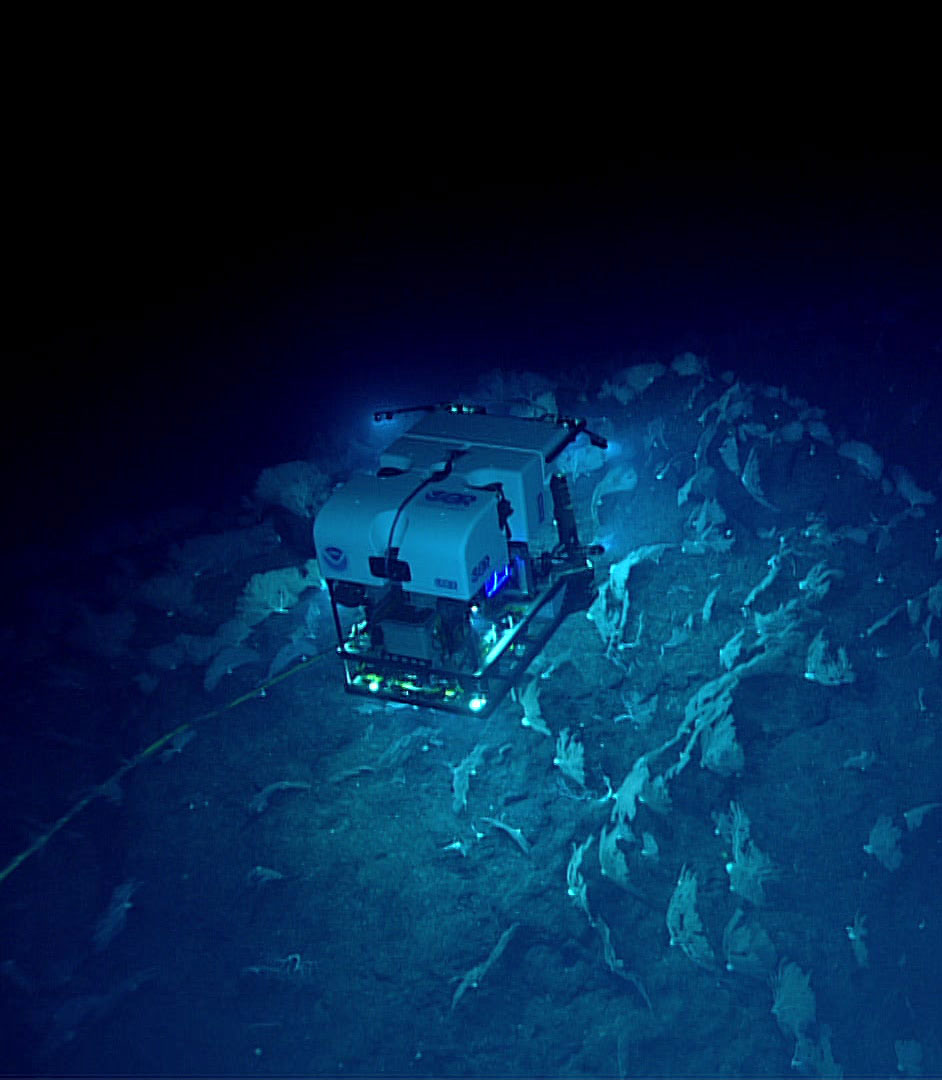

Rock formations like seamounts provide hard surfaces for sessile (stationary) animals like deep-sea corals, sponges, and anemones to grow on. On Retriever Seamount in the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, both corals and sponges were abundant and diverse. Mobile animals included fish, crabs, and squat lobsters. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (mp4, 136.1 MB).

Sponges thrive on seamounts like this unnamed seamount in the Pacific near Johnston Atoll. Sponges in this alien-like community, composed almost exclusively of glass sponges, were uniformly oriented with the direction of the current, which they rely upon to deliver their food. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2017 Laulima O Ka Moana. Download largest version (mp4, 40.3 MB).

Seamounts rise from the seafloor; canyons cut into it. Their steep slopes affect the flow of the water around and within them. Focused currents transport food and wash away sediments in some areas, exposing hard, rocky surfaces. This results in a dependable food supply and varied physical landscape (e.g., walls, boulders, rocky ledges and outcrops, rubble fields, soft sediments) that enables life on seamounts and in canyons, on the seafloor and in the water column, to flourish.

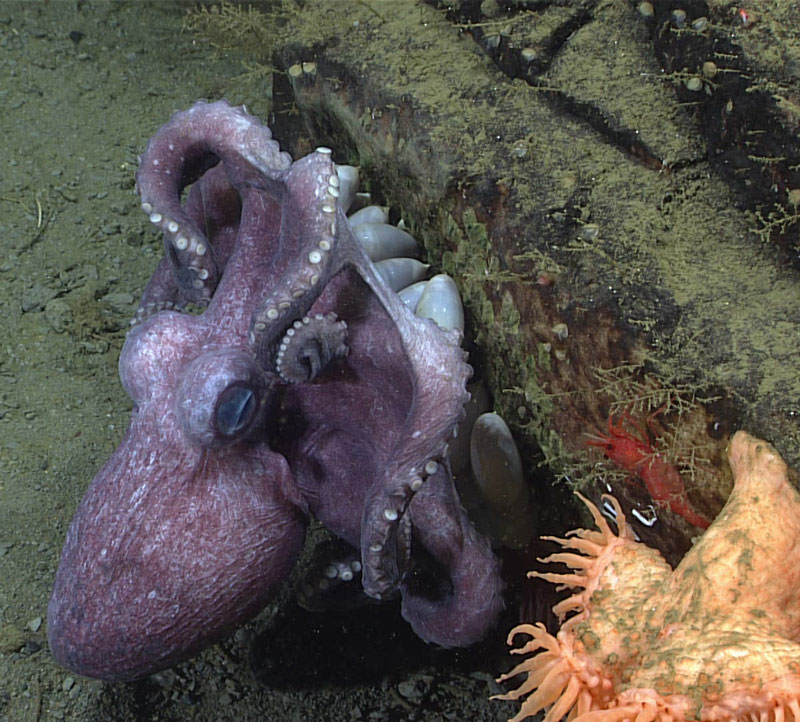

In the deep ocean, some of the organisms that inhabit seamounts and canyons include deep-sea corals, sponges, and anemones, which are sessile (stationary), in addition to fish and invertebrates like crabs, sea spiders, urchins, sea stars, sea cucumbers, worms, shrimp, octopods, squid, and jellyfish that move freely across the seafloor and/or within the water column.

Numerous important and long-living species live in submarine canyons. These large, healthy walls of bubblegum coral (Paragorgia sp.) in Baltimore Canyon off the coast of Virginia have been around a long, long time, and serve as important habitat for other animals. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download largest version (mp4, 131.4 MB).

The high biodiversity of canyons is typically attributed to their hard surfaces, but their sedimented seafloor can also be full of life. In Umnak Canyon in the Gulf of Alaska, the surface of the seafloor, both hard and soft, was covered with creatures, including fish, crabs, sponges, sea stars, anemones, an octopod, and many, many brittle stars! Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download largest version (mp4, 80.8 MB).

Related Links

- Canyons and Seamounts: Deep, Steep, and Worth Exploring — Deep Connections 2019

- Exploring Our Deepwater Backyard — Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014

- Why are seamounts "hot spots" for biodiversity?

- Mysteries of the Deep: Exploring Canyons Along the Atlantic Margin — Windows to the Deep 2018

- Seamounts | Deep-Sea Canyons — Education Themes

Deep-Sea Corals and Sponges

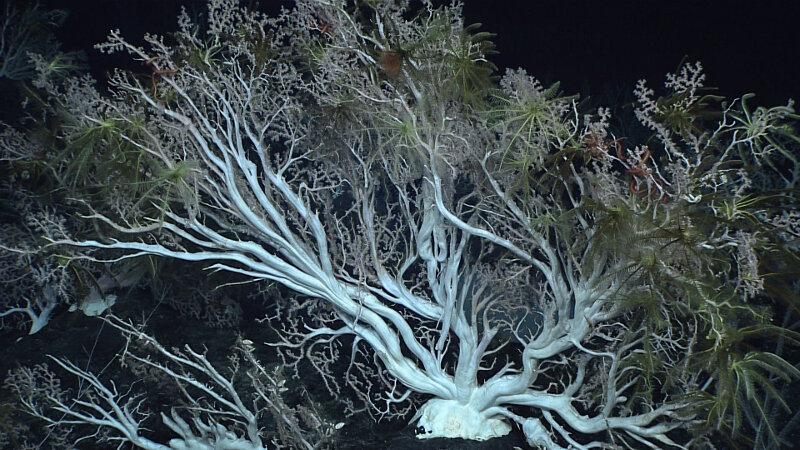

Corals and sponges are typically equated with shallow, tropical waters, but they are also resident in the deep ocean. Here, they commonly gather in areas of high current, where the food supply is steady and hard surfaces are most plentiful — like seamounts and canyons. They attach themselves to these surfaces (or anchor themselves in the soft sediment, in some cases), for the entirety of their lifetimes — which can be hundreds or thousands of years — adding three-dimensional structure to the seafloor.

Deep-sea corals and sponges are microhabitats that offer other invertebrates and fish a home base, refuge from predators, and places to feed, breed, and nurse their young. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2017 Laulima O Ka Moana. Download largest version (mp4, 186.9 MB).

Hard surfaces provide an ideal surface for corals to grow upon. Once established, they provide habitat for a variety of animals, much like trees do on land. This subsea "forest" seen in the central Pacific consisted of hundreds, if not thousands, of coral colonies, which was host to crinoids, zoanthids, brittle stars, gooseneck barnacles, and more. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download largest version (mp4, 23.6 MB).

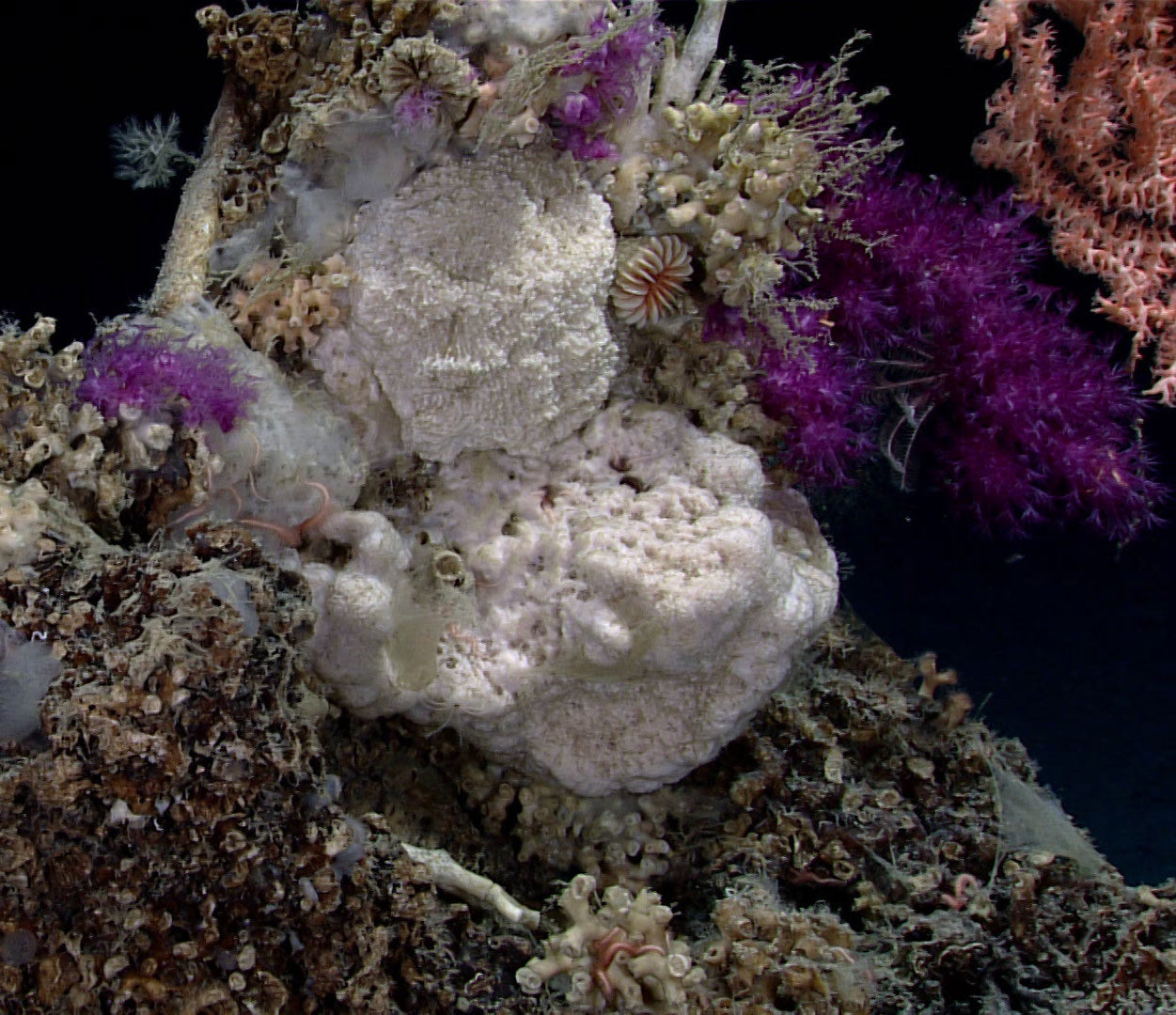

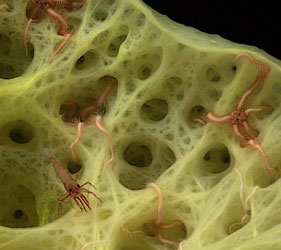

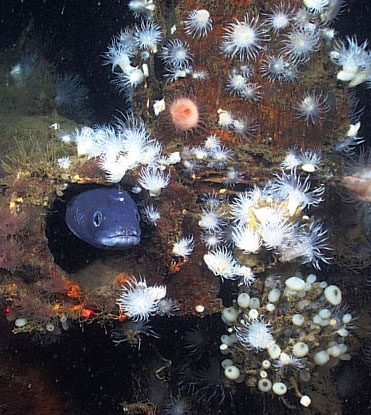

Like trees provide structure and habitat for insects, birds, and other animals, deep-sea corals and sponges provide structure and habitat for numerous marine species and are the foundation of thriving ecosystems throughout the global ocean. These biogenic habitats (habitats formed by living organisms) are habitats within habitats (or microhabitats) that offer other organisms a home base, refuge from predators, and places to feed, breed, and nurse their young.

Desmophyllum pertusum (previously called Lophelia pertusa) and other reef-building deep-sea corals foster high biodiversity in an otherwise apparently barren area of the ocean. Many of the organisms found at such reefs are not known to live in other places. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-Sea Exploration. Download largest version (mp4, 43 MB).

Several species of sea anemones and barnacles attach themselves to corals and sponges, using them as a home base. This stalked glass sponge was occupied by gooseneck barnacles, tiny anemones, and brittle stars. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download largest version (mp4, 30.1 MB).

Deep-sea corals (also known as cold-water corals) and sponges come in varying sizes, shapes, colors, textures, and quantities. Deep-sea corals are actually colonies of small animals that build a common skeleton. They live in individual colonies as well as in coral gardens and extensive coral reefs and mounds. Similarly, sponges also occur on their own or as part of a sponge garden (or grounds). And sometimes they come together to form a deep-sea coral and sponge community, further enhancing their habitat value.

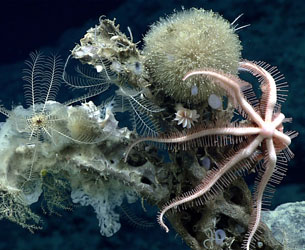

Among the animals that benefit from the habitat provided by deep-sea corals and sponges are squat lobsters, shrimp, crabs, sea spiders, barnacles, amphipods, sea stars, brittle stars, crinoids, anemones, worms, fish, benthic ctenophores, and jellyfish.

Some crabs, like the one seen here, carry sponges on their backs, taking advantage of the sponge’s sharp spicules for protection against predators. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download largest version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Deep-sea corals alter the seafloor by adding a structure for other invertebrates to use to reach higher into the water column, where food is more readily available. This is demonstrated by the many crinoids, or feather stars, seen perched on this large pink coral (Hemicorallium sp.). Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Related Links

- Unforeseen Abundance of Deep-Sea Coral Habitat — Windows to the Deep 2019

- Coral Reef Ecosystems in the Deep Sea — Southeast Deep Coral Initiative

- Life in the Deep-Sea Coral Forest — Deepwater Wonders of Wake

- Deep-Sea Corals — Education Theme

- Characterizing U.S. Deep-Sea Corals and Sponges

Chemosynthetic Features

As on land and in the shallow-water habitats with which we are most familiar, much of life in the deep-ocean depends on a food chain based on photosynthesis — but not all of it. Chemosynthetic features like hydrothermal vents and cold seeps are ecologically rich habitats that are powered by chemical energy, not light energy.

The existence of this alternative life-fueling process — called chemosynthesis — had been hypothesized, but was not confirmed until the 1970s, when researchers on human-occupied vehicle Alvin first encountered chemosynthetic communities around deep-ocean hydrothermal vents.

The Moytirra hydrothermal vent field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge consists of active and inactive hydrothermal chimneys. On and around the active chimneys, species known to inhabit vents — including eelpouts (Zoarcidae), shrimp (Mirocaris sp.), limpets (Peltospira sp.), and crabs (Segonzacia sp.), were plentiful. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Voyage to the Ridge 2022. Download largest version (mp4, 101.3 MB).

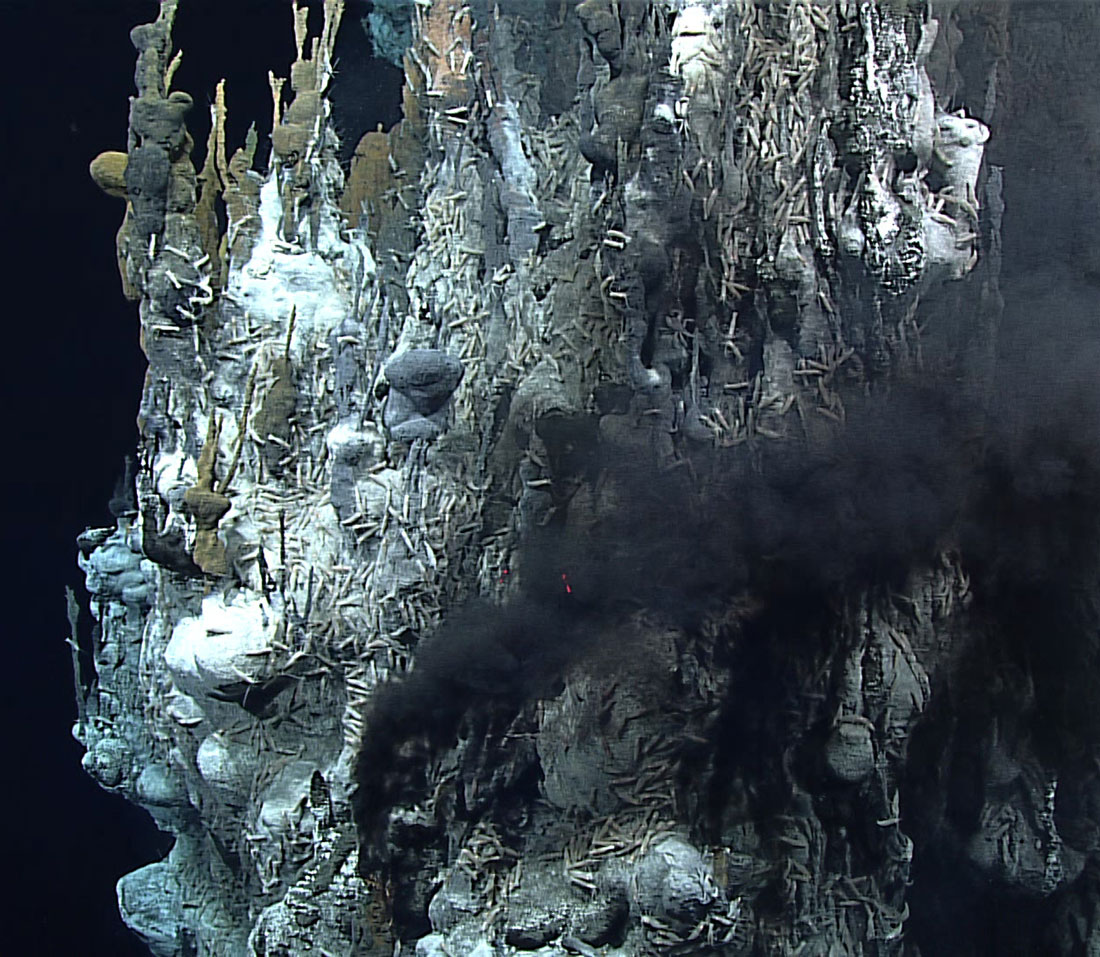

This hydrothermal vent near the Mariana Islands was first imaged in 2016. The base of the chimney is extinct sulfide, but the top is active, with several black smoker orifices, beehive structures, chimney spires, and iron and anhydrite precipitate. The water temperature at the vent was 339° Celsius (642° Fahrenheit), and the vent was colonized by numerous organisms, including shrimp (Rimicaris sp.) and tubeworms (Paralvinella sp.) directly at vent effluent sites, and crabs (Austinograea williamsi) and limpets just inches to feet away. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download largest version (mp4, 75.6 MB).

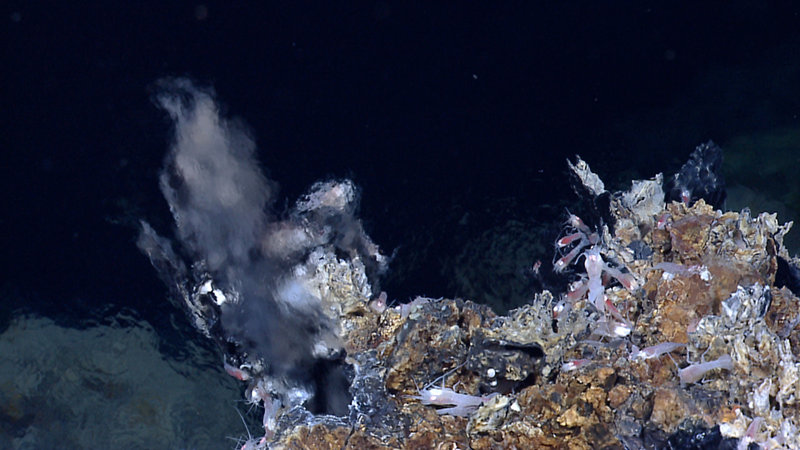

Driven by volcanism, hydrothermal vents occur at tectonically active areas. They are short-lived openings in the seafloor that spew super-heated, chemical-rich fluids into the ocean. Chemosynthetic microbes — some of which are free-living, and some of which live symbiotically within the tissues of other organisms — are then able to use dissolved chemicals in ocean water to produce organic compounds (food), forming the foundation for diverse chemosynthetic communities.

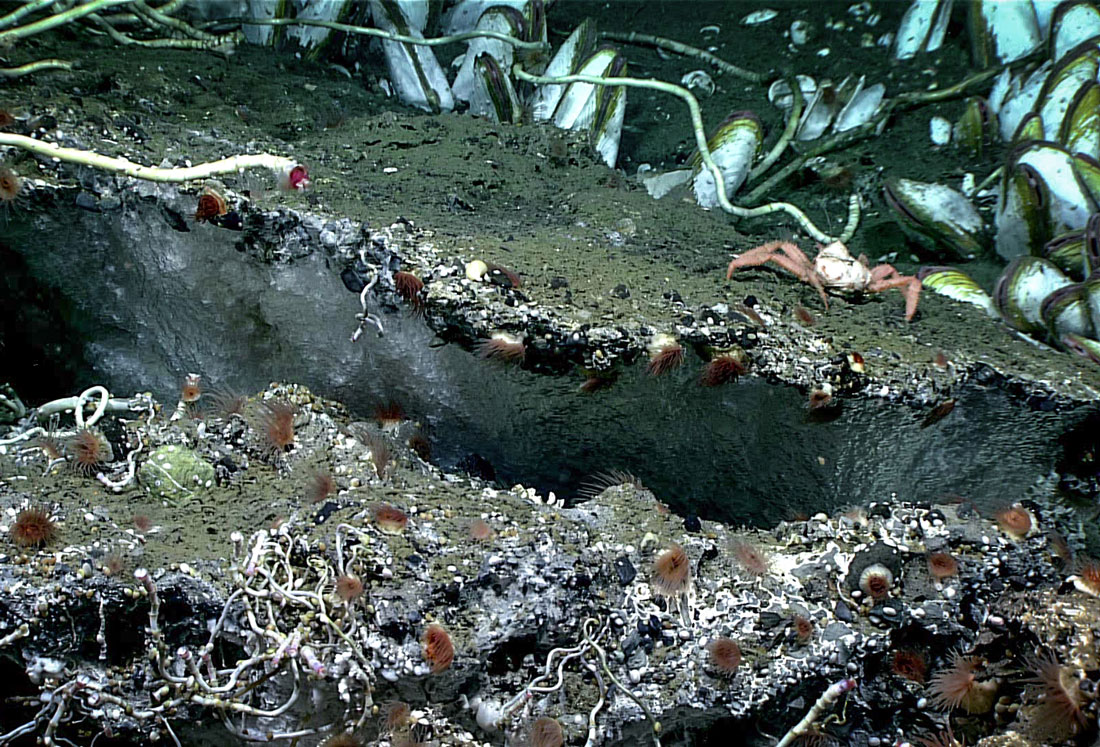

Some animals, like chemosynthetic mussels and tubeworms, are dependent on the chemicals at chemosynthetic hotspots to survive, while others are drawn in by the additional habitat and food found at these sites. Over time, the species composition in these habitats will change in a process known as ecological succession. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download largest version (mp4, 108.2 MB).

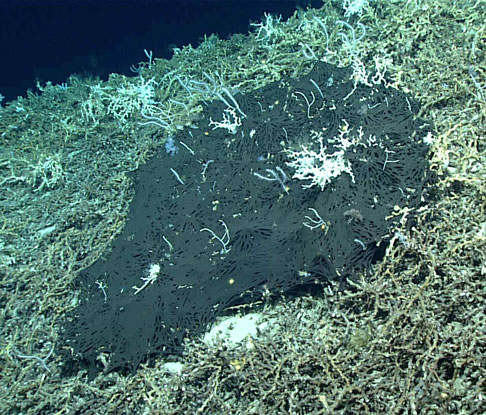

When side-scan sonar showed a cluster of large structures at a depth of 1,900 meters (6,234 feet) in the Gulf of Mexico, scientists thought it might be a shipwreck, but it soon revealed itself to be something else entirely: a natural asphalt extrusion eventually dubbed a "tar lily." The presence of chemosynthetic organisms (tubeworms, microbial mats, and shrimp) indicated that hydrocarbon seepage was actively occurring, while the hard "petals" of the structures provided habitat for other organisms, including anemones, sponges, barnacles, octocorals (bamboo corals and sea pens), and squat lobsters. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download largest version (mp4, 29.1 MB).

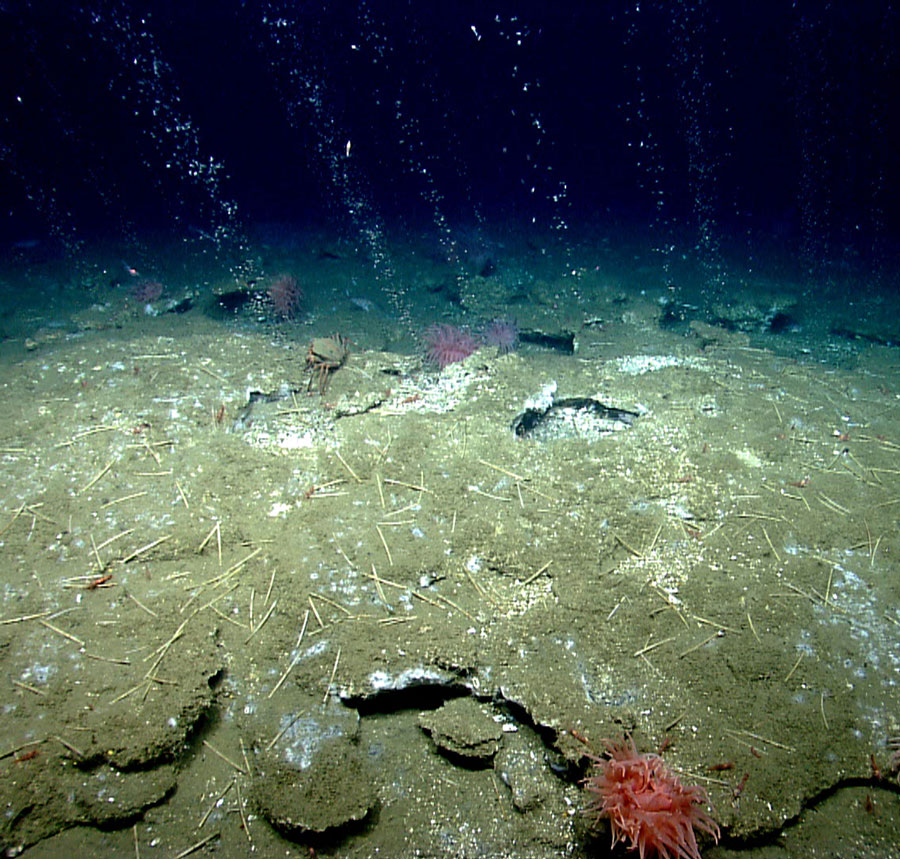

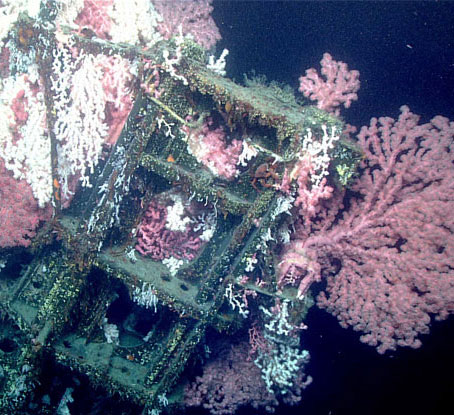

Chemosynthetic life has since been found in a variety of other environments, including whale falls, shipwrecks, and cold seeps. Cold seeps are places where chemical-rich fluids and gases escape through cracks and fissures in the ocean floor due to pressure. Unlike hydrothermal vents, cold seeps provide a relatively stable habitat and have little variation in temperature from surrounding waters.

The communities that develop in these habitats can vary greatly from one location to another. Some of the organisms that are known to thrive on and around chemosynthetic features include microbes, tubeworms, clams, mussels, crabs, squat lobsters, shrimp, fish, and octopods.

This extinct hydrothermal vent chimney was discovered while exploring a volcanic dome in the Mariana Islands region with remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer. The cessation of the flow of chemical-rich fluids at an extinct vent means that organisms that depend on these chemicals can no longer survive there. But, an extinct vent is still an important habitat. With its hard surface providing a place for organisms to attach and settle and its tall form reaching into the water column, an extinct vent can be prime real estate in the deep ocean. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download largest version (jpg, 439 KB).

The shimmer effect seen here demonstrates the density contrast between seawater and vent fluid at an active hydrothermal vent southeast of the central Von Damm hydrothermal field in the Mid-Cayman Rise. Note the filaments of bacteria and the hydrothermal shrimp in the immediate vicinity of the active fluid flow. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Mid-Cayman Rise 2011. Download largest version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Related Links

- What is the difference between photosynthesis and chemosynthesis?

- What is the difference between cold seeps and hydrothermal vents?

- Cold Seeps | Hydrothermal Vents and Volcanoes — Education Themes

- Newly Discovered Aleutian Margin Cold Seeps Host Gas Hydrate and Dense Colonies of Tubeworms — Seascape Alaska

- Hydrothermal Vents — 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas

Water Column

When imagining a habitat, it's easy to picture it from a human perspective: the ground below, the act of moving across a landscape, the presence of permanent features. But consider the water column, where vertical space is as easily navigable as horizontal space. The water column encompasses the entirety of the expanse between the surface of the ocean to the seafloor, with an average depth of about 3,682 meters (12,080 feet). With the ocean covering 70% of the Earth's surface, the water column is estimated to comprise 95 to 99 percent of the total livable volume of the planet, making it the largest habitat on Earth.

In 2019, this giant squid, at least 3 meters (~10 feet) in length, was seen in the midnight (bathypelagic) zone at a depth of 759 meters (2,490 feet). This was the first time that a giant squid had been filmed in U.S. waters and only the second time one had been filmed alive anywhere. The vast, remote, and extreme nature of the deep water column makes it a challenging habitat to explore. Video courtesy of Edie Widder and Nathan Robinson. Download largest version (mp4, 11 MB).

Understanding the deep scattering layer, a region in the water column that reflects sound due to the high density of marine organisms found there, illuminates the largest migration on Earth — diel vertical migration. Every day, billions of organisms, mostly zooplankton, move up into shallow water at night and return to the dark, deep waters when the sun rises. This phenomenon is significant enough to play a role in the ocean food chain as well the carbon cycle. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Windows to the Deep 2021. Download largest version (mp4, 237 MB).

But all is not uniform throughout these depths. Pressure, light, temperature, oxygen, and mineral nutrients are all important characteristics that vary throughout the water column, influencing where organisms are able to live and the adaptations they've developed over time. Scientists categorize the water column into five zones based on depth: the sunlit (epipelagic), twilight (mesopelagic), midnight (bathypelagic), abyssal (abyssopelagic), and hadal (hadalpelagic) zones.

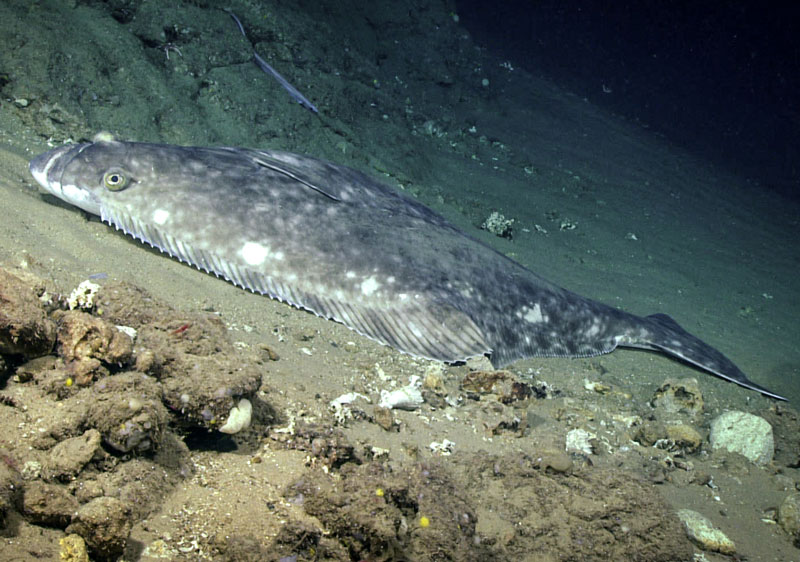

This dragonfish, Melanostomias melanops, displays several adaptations frequently seen in the deep sea, including a dark-colored body, bioluminescent photophores, and a "fishing lure" dangling from its chin to attract prey. These fish are found throughout the North Atlantic Ocean at depths ranging from 50 to 1,500 meters (164 and 4,921 feet). Large adults in this family (Stomiidae) often spend time very close to the seafloor, as seen here, but most other individuals can be found in the midwater water column. Video courtesy of the NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2019 Southeastern U.S. Deep-sea Exploration. Download largest version (mp4, 48.7 MB).

Marine snow is a critical source of food for animals in the deep ocean. It consists of mostly biological debris that originates in the top layers of the ocean and drifts to the seafloor, accumulating other floating debris as it sinks. Video courtesy of NOAA/UAF/Oceaneering. Download largest version (mp4, 7.2 MB).

The creatures that call this habitat home are diverse and plentiful. The thin layer of sunlit water at the sea surface hosts photosynthetic phytoplankton that form the basis of the ocean food chain, supporting a wide array of life there and in the depths below through the production of marine snow. The twilight zone, where the last rays of light begin to fade, may hold more fish by mass than the rest of the ocean combined. Both here and in the sunless regions of the ocean, many organisms have evolved fantastical traits to survive in the dark, food-scarce waters of the deep sea. Zooplankton, fish, gelatinous animals, and squid are just some of the creatures frequently seen while exploring midwater regions. However, the deep water column remains so largely unexplored that we lack even a basic inventory of the animals living here.

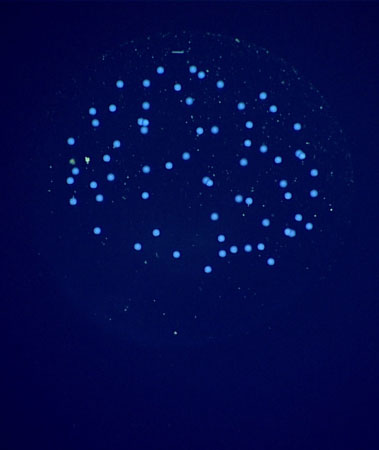

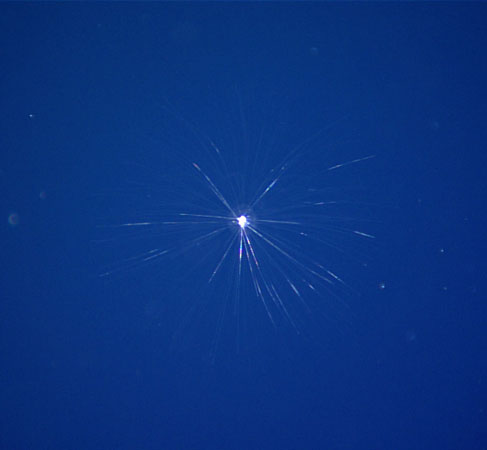

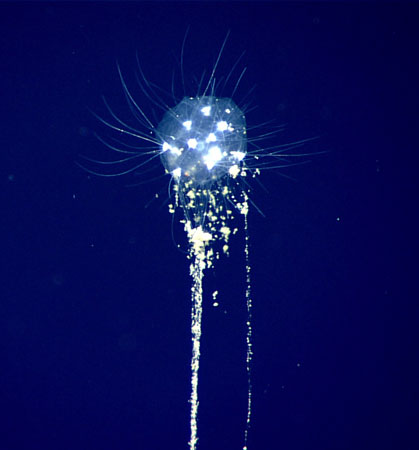

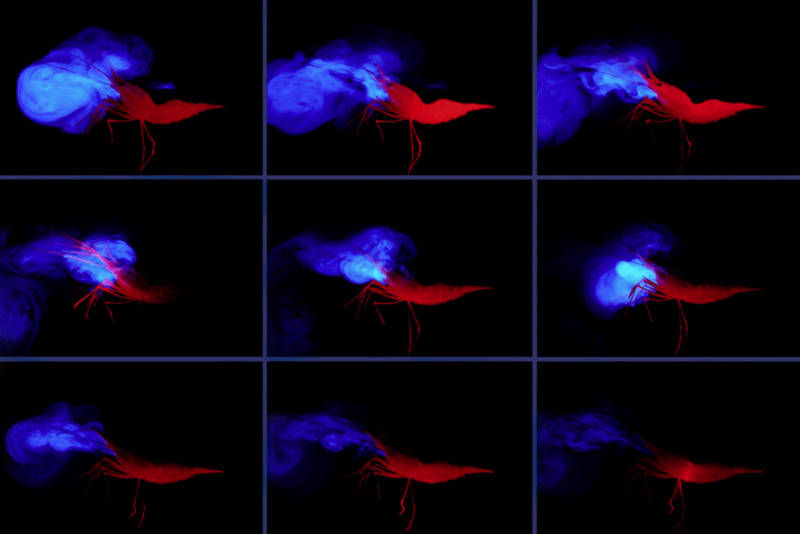

In a startling display, this sequence shows the deep-sea pandalid shrimp Heterocarpus ensifer "vomiting" light from glands located near its mouth. Bioluminescence is used by organisms for a variety of reasons: to warn or evade predators, to lure or detect prey, and for communication between members of the same species. It has been estimated that 90 percent of the animals living in the water column are bioluminescent. Image courtesy of Journey into Midnight: Light and Life Below the Twilight Zone. Download largest version (jpg, 53 KB).

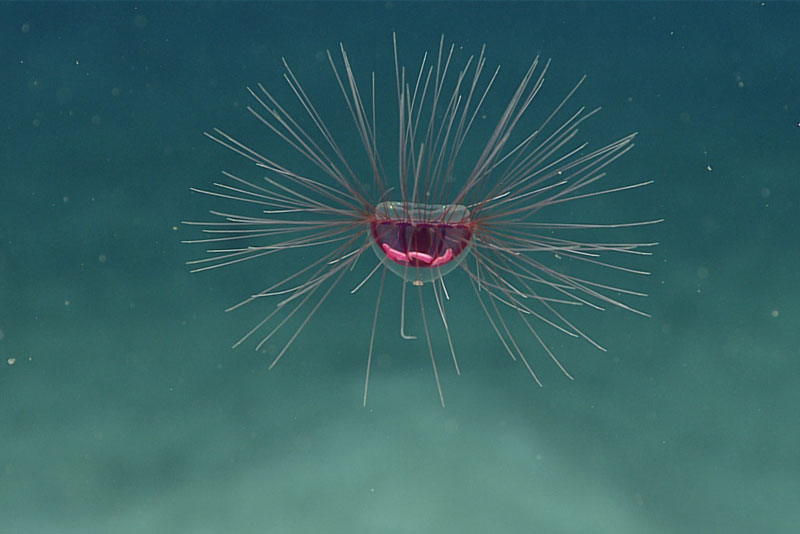

This Rhopalonematid jelly (Crossota millsae) was observed at a depth of 1,015 meters (3,330 feet), the upper edge of the midnight (bathypelagic) zone. Known from both the Atlantic and the Pacific, jellies similar to this have been found not too far from the seafloor, suggesting a linkage between the ocean bottom (benthos) and the water column. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Exploring Deep-sea Habitats off Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Download largest version (jpg, 852 KB).

Conclusion

But that’s not all! These are only some of the habitats of the deep. Other important deep-ocean habitats include geological formations like trenches, troughs, ridges, and knolls (like seamounts, but smaller); shipwrecks and other human-made structures; and, of course, there’s the abyssal plain, which makes up most of the seafloor.

Humans occupy only a small percentage of our planet’s habitable environment. Deep-ocean habitats are some of the largest living places on Earth, but they’re also the least explored and understood. That means there’s so much to learn about them and the species they host, many of which may be beneficial in ways we don’t yet know about.

NOAA Ocean Exploration is committed to exploring the deep ocean and sharing our findings to help improve understanding of these habitats, where they’re located, how they’re connected, what types of organisms they support, and how they are important to us.

For updates on NOAA Ocean Exploration activities and discoveries, explore our website; like us on Facebook; follow us on LinkedIn, X/Twitter, or Instagram; or subscribe to our YouTube channel.