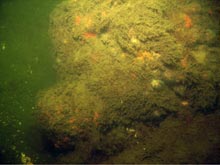

To the untrained eye this might look like a rock, but it's actually the muzzle of an 18th-century nine-pound gun. Objects protruding from the sea floor, like this one, are known as “proud” objects. Click image for larger view and image credit.

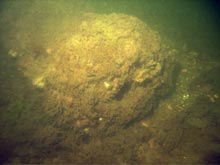

The cascabel (a rounded projection behind the breech of the gun) is on the other end. Comparing sonar images with photographs can help technicians identify what they are seeing, as can data from magnetometers (instruments that detect the presence of iron and/or steel). Click image for larger view and image credit.

NOAA’s Knowledge of Sunken History Helps Navy Identify Mines

May 18, 2008

Commander John E.M. Brown, USN (RC)

NOAA-Navy Liaison for AUVfest 2008

Office of Naval Research

The U.S. Navy is interested in technologies and methods that can help in its mine countermeasure mission, and NOAA is interested in those that can assist in investigations of maritime archaeological sites. Many of the autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) at AUVfest 2008 were developed for the Navy mine applications, but their systems can also sense archaeological artifacts. This means the Navy’s investment in technology has a dual benefit for the country.

As we sat down after the first good day of operations for the daily “Hotwash” — the meeting where we share data and findings — I thought about the theme of AUVfest 2008: “Partnership Runs Deep: Navy Unmanned Mine-hunting Technologies Help NOAA Explore Sunken History.” It occurred to me that NOAA’s archaeological research can also help a Navy interest.

The first step in mine-hunting is searching and mapping an area, and noting mine-like objects as possible targets of interest. The second step is to classify the mine-like object as either a mine or a non-mine, and if possible, identify the actual type of mine. The final step is to “neutralize” the mine by destroying or removing it.

AUVs can search a large area and map mine-like objects using sonar. An AUV with a video camera, or another kind of electro-optical sensor, can be vectored (guided by radio communication) to each target of interest to classify and identify each object. Still, the process isn’t necessarily automatic. The pictures recorded need to be evaluated by a trained mine countermeasure operator, using a library of specific, identified items. While the processing algorithms (computations) used onboard AUVs are quite sophisticated, the actual identification of a mine is a still a mix of art and science. The experience level of an mine countermeasure operator still plays a vital role in interpreting the AUV data, and will continue to do so.

Confounding the process of identifying mine-like objects are environmental conditions, such as ocean depth, materials or substrate on the ocean bottom (e.g., sand, rocks, mud, etc), and currents. Trying to identify mines, which are designed to blend in to the environment, is particularly challenging when the ocean bottom is cluttered with rocks or debris.

Using sidescan sonar, AUVs captured this image of a cylindrical object on the sea floor that looks similar to a cannon. On closer inspection, however, researchers realized that it lacked the characteristic features which are evident on a cannon from the HMS Cerberus site. It's important for archaeologists to be able to closely examine each object — to establish its context in time and space — in order to interpret past events. Click image for larger view and image credit.

While marine archaeologists may not have as much experience using AUVs as does the Navy, they do have useful knowledge about the historical context of an underwater site, and they may have documentation of the debris fields. Even better, marine archaeologists may have a catalog of underwater photographs that show, for instance, what an 18th-century naval cannon looks like on the ocean bottom after 200 years.

Once the Navy looks at the AUV data, the operator can perform a search and quickly match the location of a sonar image to the known location of an underwater archaeological artifact. If NOAA provides close-up underwater photography of the artifact being investigated, the Navy could help groundtruth the sonar image with the photo, adding to the library of positively identified objects and enhancing the overall mine warfare database. Photos can also help us make good guesses about objects and, through diver verification, prove that our suspicions were correct or incorrect — a useful step that we couldn’t take without the documentation archaeologists often have.

All federal agencies and states are tasked with the protection of cultural resources, and those on submerged lands are no exception. Because monitoring is not easy, and artifacts are sought after, archaeologists have to contend with "when and how" to release information about new or important cultural sites (especially those that have not been fully catalogued and described) to the public.