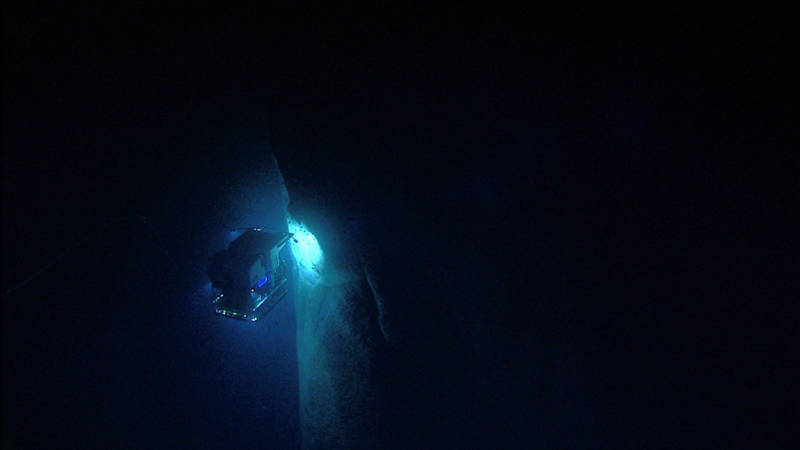

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer investigates an unexplored canyon wall. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Recently, the Okeanos Explorer team was asked what advice we would give to students or individuals who are just starting their careers and are interested in getting into the ocean exploration field. We posed this question to our team, and below you can read some of their responses which includes advice for young aspiring explorers. We've also included each person’s title as well as his or her role in the current expedition. You can also learn more about the background of our current at-sea team here.

The view from the control room as Deep Discoverer collects high-resolution imagery of a deep-sea sponge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 968 KB).

Brian Kennedy, NOAA Corps Officer

Role in this expedition: Expedition Coordinator

Be persistent but nice. Just because they said no once does not mean they will say it the third time. But remember to be nice about it, because no one wants to help someone who is not pleasant to be around. Also, take advantage of every opportunity you can because you never know where it will lead.

Scott France, Deep-sea Biologist

Role in this expedition: Science Team Lead

Best advice for a young person? Stay curious! Ask lots of questions and read lots of books (or electronic media), not just on science but on any topic, including fiction. Reading often improves writing skills. Get the fundamentals in school. Lots of people find this uninspiring and off-putting, but you absolutely need to know how to walk before you can run. So a good foundation in science and math courses is critical to later becoming a marine biologist. Get involved! Most undergraduate programs provide opportunities for students to be involved in research, either as an intern, enrolled in a special projects course, or as a volunteer. Ask around at your school if there are openings to work on research projects. Having elements from all of these areas will vastly improve your chances of getting into a competitive graduate school program where you can specialize in marine biology and have the opportunity to continue to explore our ocean.

Jared Drewniak, Telepresence Engineer

Role in this expedition: Telepresence Team Lead

Ask lots of questions and never be afraid of looking dumb. It's the people who ask lots of questions and try everything that end up learning the most.

Susan Schnur, PhD Graduate Student in Marine Geology

Role in this expedition: Co-Science Team Lead

1) Become a good writer and learn to love writing. Many professors and graduate students say they hate writing, but as a researcher writing is an important part of your job. To get other people excited about what you're studying you have to be able to explain it clearly and concisely.

2) Be persistent. Don't be discouraged if things don't work out for you right away. Scientists frequently face failure – in fact, it's an important part of the job. Failure tells us what doesn't work so we can improve for next time. So if you apply for an internship, summer program, or scholarship and aren't accepted, try again next year. In the meantime, look for other opportunities – there are many ways to get involved in science.

3) Be proactive. If you have a vision of what you want to study in the future, actively seek out opportunities that will get you closer to that goal. Talk to people who are experts in the things you're interested in. Ask them how you can find out more or get involved in their work. Keep an eye out for interesting opportunities and don't be afraid to take on a challenge.

Emily Rose, NOAA Corps Officer and Okeanos Explorer Operations Officer

Make sure you pay attention in math and science classes and learn as much as you can in these subjects. Also, do not be afraid to ask questions, this is the first step to making discoveries.

Roland Brian, Video Engineer

Role in this expedition: Video Engineer

I wear many hats as an exploration team member, but my primary work revolves around video engineering. If you want to do what I do, grab a camera and record various videos and put together your own stories. It takes practice to be able to tell a story with video and audio in a way that your audience will find engaging and want to keep watching. Try to keep your stories short, as most people will easily lose interest if the story is too long or not presented in a way that makes them want to see and hear more. Also, don't go overboard with special effects; instead, use basic effects to transition from one video to the next while allowing the audio to overlap from one video to the next. Try a few short stories, about two to three minutes long, with each shot typically being no longer than five to eight seconds each. After you master that aspect, then mix it up with a little subtle music in the background or between comments. This will allow the viewer to process the message before the next comment is made and help get the messages across.

Jeff Williams, Electrical Engineer

Role in this expedition: Remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pilot

I'd say to them to get a good, solid engineering degree and then search out ROV/AUV opportunities in academia and industry. Don't be afraid to put themselves out there and offer to get involved in some field experience at any level.

Emily Crum, Online Communications Manager

Role in this expedition: Webmaster, Social Media Manager

I'd say to explore every avenue that seems interesting to you and, while it is important to have a plan, don't worry too much about where you're going to end up. Take the classes and work opportunities that are engaging to you, even if they don't always seem to fit together, and never stop taking them...even if you think you are "done," you may stumble onto something totally new that will make you better at your job or take you in an entirely different direction. My education and work experiences are in science (mostly geology), art studio and graphic design, communications, policy, and business; kind of random and all over the place, but they come together nicely for someone who is working to communicate about federal science online (a job, by the way, that I never envisioned doing...until suddenly, I was).

Brendan Reser, Oceanographer/Data Manager

Role in the Expedition: Data Management Lead

Learn a programming language or three. It's not just for computer scientists anymore. Understanding how to write code is a useful, and increasingly important skill, in any technical or science field. By and large, coding is solving a puzzle. How you solve it is up to you. Marine science is a constantly evolving field, and most of the time there's not necessarily a direct route into it. I started out studying vertebrate biology in the southwest desert. Be adaptable to situations as they emerge. Also, learn to scuba dive. As fascinating as it is to explore and research the ocean from the surface, physically experiencing it for yourself is a whole other world.

Tim Shank, Deep-sea biologist

Role in the Expedition: Shoreside Science Team

My advice? If you want to be a marine biologist, I would suggest that, in addition to seeking people who do what you want to do and learning about what they do, learn skills relevant to the field, like computer science and genetics, and apply them to the current research questions in marine biology. Also, it’s really important that you believe in your chosen field and what you do in it.

Lindsay Mckenna, Physical Scientist/Hydrographer

Role in this Expedition: Mapping Lead

Get involved in variety of different internships and projects and keep an open mind with each one. I didn't take a direct path to ocean exploration; for example, I interned as a park ranger in the Pacific Northwest and spent a summer studying groundwater using NASA satellites. In graduate school, I landed a competitive internship that introduced me to ocean exploration and I was hooked! Although some of my experiences were not directly related to exploring the ocean, each one provided me a unique perspective that I use as a professional today.

Dave Wright, Electrical Engineer

Role in this expedition: ROV Pilot

If you have an interest in electronics, computers, or mechanical engineering, then start right now learning how to build things or program things. You will learn later in college about the theoretical side of your interest, but what you must teach yourself is how to work with your hands to create what you imagine, to experiment, to explore…

Catalina Martinez, Oceanographer

Role in this expedition: Shoreside Operational Support

Look beyond your immediate environment and expose yourself to new things so that you don't limit your vision of who you can become. Seek new opportunities and be sure to surround yourself with good people who can provide essential guidance, support, and mentorship. Figure out what it is you are passionate about and be prepared to work hard to achieve your goals. Be determined to obtain the education of your choosing and although there may be obstacles, learn how to overcome them so they do not define your future. And for those who, like me, may not have started out with the best circumstances, always remember that where you begin your life does not have to define where you end up.

Kasey Cantwell, Field Operations Specialist

Role in this expedition: Web Coordinator

Take advantage of every opportunity you have to gain a diversity of experience. Even if you are not exactly sure what you what to do for your career, an internship or a specialized class can help you figure it out (or help you figure out what you don’t want to do).

Adam Skarke, Marine Geologist

Role in the Expedition: Shoreside Science Team

Almost everyone involved with the Okeanos Explorer Program has a background in science or engineering. Doing well in science and math courses in school is a great foundation for a career in ocean exploration. Although most aspects of ocean science and engineering are not specifically taught in schools, there are many books and online resources available on these topics. Taking advantage of these resources and educating yourself about oceanography, ocean engineering, and the history of ocean exploration will prepare you well to be future ocean explorer.