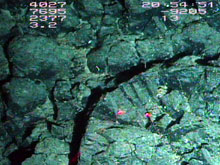

Photographed by DSV Alvin, these rocks are coated with hardened manganese deposits up to several centimeters thick. Click image for larger view.

Rocks Are Everywhere, but We Like Them Fresh

August 6, 2004

Dr. Randy Keller

Professor

Department of Oceanography

Oregon State University

We had our work cut out for us yesterday, searching the upper flank and peak of Denson Seamount for the rocks we need for our geological studies. To understand the volcanic history of this seamount we need to determine the age and chemical composition of at least a few of the lava flows that created it. That's why we need rocks that are as close to their original physical and chemical form as possible.

Unfortunately, seawater eats away at volcanic rocks over millions of years, altering the rocks' original minerals and changing their chemical composition. We can compensate for some of these chemical changes when we analyze the rocks in our laboratory, but it is much easier and more reliable to collect unaltered, or "fresh," rocks in the first place.

Where do we look for fresh rocks? Rocks that are scattered loosely on the sea floor are the most exposed to seawater alteration -- so we definitely want to avoid those. Sometimes we have to dig and tug at rocks that are firmly embedded in the mountainside to find one that still looks pristine enough to keep. The deep submergence vehicle (DSV) Alvin has incredibly strong "arms" and "fingers" that, given enough time, can pry loose almost any rock.

On seamounts older than a few million years, it is not unusual to find almost all of the rocks coated with hardened manganese deposits up to several centimeters thick. Manganese precipitates naturally out of seawater as a black layer that coats the rocks, masking their features and making volcanic rocks very difficult to recognize on the sea floor.

Fortunately, the Alvin pilots love a challenge, and they will do whatever they can (within the bounds of safety, of course) to get us the samples we need. They seem to enjoy their work, and they don't consider a dive successful until they have satisfied their passengers -- the scientists.

Once we have the rock samples aboard the R/V Atlantis, we crack them open with a hammer or cut them open with a saw to reveal a fresh interior surface. We can then use a microscope or a magnifying lens to look for minerals that help us determine the rock's volcanic origins.

So far, we have what looks to be the beginnings of a good rock collection from these seamounts. Not all of them are as fresh as we would like, but every field geologist -- whether working on land or at sea -- has to deal with the realities of what rock samples are available for collection and study.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.