Published August 30, 2019

When you’re a marine scientist headed back to port after a few months at sea, you can fish, read a few books, or collect more data. On the way home in October 2010, researchers on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer decided to spend their time towing an odd-looking device more than 5,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean to measure plankton near the ocean surface. But that wasn’t enough. They also used a separate instrument known as the “Manta Net” to grab bits of a floating stew of plastic junk known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch.”

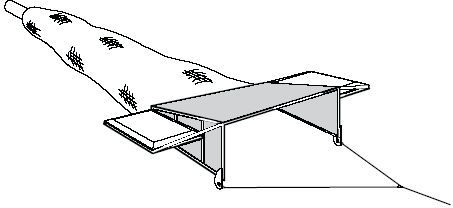

Illustration of the “Manta Net.” Image courtesy of NOAA Fisheries Service’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

This trans-Pacific trawl for plankton and plastic took place after the Okeanos Explorer had just finished its remarkable first official cruise exploring the deep ocean of Indonesia, the 2010 Indonesia-USA Deep-Sea Exploration of the Sangihe Talaud Region (INDEX-SATAL) expedition.

When INDEX-SATAL concluded, the Okeanos had to sail home to the United States, and NOAA oceanographer Michael Ford decided to make good use of that return trip. “It was an opportunistic event,” said Ford, oceanographer at the Marine Ecosystems Division of NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service who led the project back in October 2010. “The concept was to take advantage of this long transect to get a small snapshot in the change of taxa of organisms. Were we going to see a decline in abundance or would we see an increase as we approached Hawaii?”

Although the return trip of the Okeanos from Guam to Honolulu and then back to San Francisco provided Ford and colleagues with the sampling opportunity, they still had to make sure the devices worked properly and that technicians onboard were trained to handle the samples.

Ford notes that despite centuries of exploration across the Pacific, no previous research cruise had sampled such a large cross section of the ocean at one time. Ford says that there was more plankton data recorded during that cruise than all of NOAA’s East Coast research labs collect during an entire year. Making a single transect is important because it allows scientists to examine a huge swath of the marine ecosystem at one time, rather than sampling discrete boxes.

The entire continuous plankton recorder sampled for 5,200 nautical miles, a record for the longest plankton tow by a U.S. ship. Ford compared the stubby-looking recorder to a “tiny, fat space shuttle with a fin on the back.”

The recorder uses a funnel to send seawater through a silk filter that is continuously rolling on a spool. The silk filter traps tiny zooplankton and phytoplankton – the basis of the marine food chain. The spools of silk were changed every second day, bathed in formalin, carefully stored, and then transported to the NOAA Fisheries Service laboratory in Narragansett, Rhode Island. From there, the samples were shipped to a plankton sorting facility in Szczecin, Poland, where they remain today and where analysis continues.

Zooplankton, normally difficult to see with the naked eye, viewed through a microscope. Image courtesy of M. Wilson, J. Clark, NOAA NMFS AFSC.

Colleagues on the cruise, including Miriam Goldstein at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, used data from the Manta Net to characterize the vast Pacific Garbage Patch. As noted in their 2013 research paper published in the journal PLOS One , the sampling revealed that the plastic varied greatly in size, from visible patches of debris to tiny microparticles that are slowly being ingested by plankton, fish, and other marine life.

Although much of the debris concentrated in the “garbage patch” is composed of small bits of plastic not immediately visible to the naked eye, large items are occasionally observed. On August 11, 2010, Scripps Institution of Oceanography SEAPLEX researchers encountered this large ghost net with tangled rope, net, plastic, and various biological organisms. Image courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The cruise also revealed that when at sea, it’s always a good idea to keep your lure in the water on the way home.