Published September 4, 2019

Sometimes scientists get lucky, even though that moment of luck is the result of years of observations, hypotheses, and intuition that turns out to be spot on. For Chris German, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, his prediction was that he could find hydrothermal vents for the first time at a deep-ocean ridge known as the Mid-Cayman Rise, a trough of deep water lying between Cuba and Jamaica.

Back in 2010, German strongly believed hydrothermal vents would be found there, even though the Caribbean Sea didn’t possess the kind of geological traits that characterized hydrothermal vents in other parts of the world’s ocean basins. For one, the seafloor wasn’t spreading fast enough and secondly, there wasn’t the volcanism that is usually associated with vents and the strange marine ecosystems that grown around them.

German had published a paper in 2010 showing that vents could occur at places where there were deep, but slow-spreading fault zones. But he wanted to prove his theory with a visit to the Mid-Cayman site. After contacts with a colleague at the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, he was named senior scientist on the 2011 Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition.

The expedition was put together rather quickly since NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer was returning to port in Key West, Florida, through the Caribbean after a deployment to the Gulf of Mexico.

Science Team Lead, Chris German, provides an overview of the expedition and science objectives to the ship’s crew at the start of the expedition. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011.

Of course, its one thing to visit a massive undersea zone, it’s another to find a vent field that could only stretch a few acres across the seafloor. After trawling the area for chemical signatures of the vents in the water column, German and his team narrowed down the search to a single area. He was helped out by scientists onshore whom he relied for expertise daily through video feeds and data-sharing telepresence, a new capability for oceanographers working aboard the Okeanos.

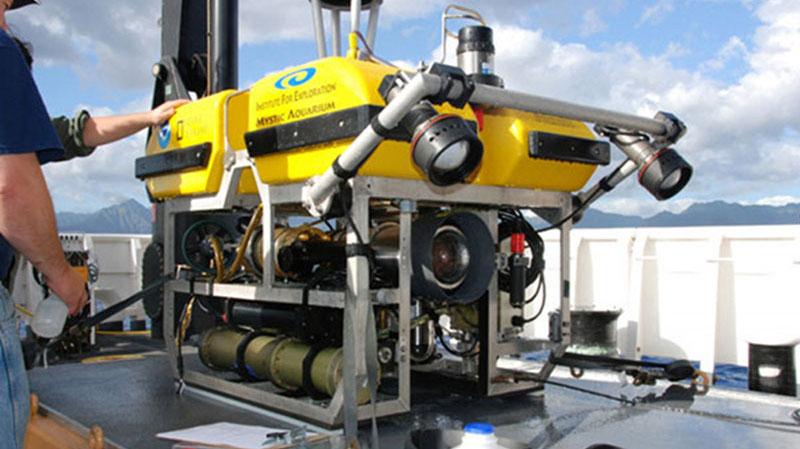

The team lowered the remotely operated vehicle Little Hercules 2,300 meters (1.4 miles) to the seafloor. Bingo.

Remotely operated vehicle Little Hercules. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011.

“The first time we hit a vent was eight seconds after we hit the seafloor on the first dive,” recalls German. “They were still opening the cameras when we landed. The bottom came into sight and we saw an eight-meter-tall white chimney.”

From the first moment of the first dive we were able to land right at the summit of the Von Damm hydrothermal field. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011.

One of the interesting geological findings during the expedition included this orifice more than 3 feet wide. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011.

Over the next few days, German and colleagues explored the vent fields and found something really weird: chemosynthetic shrimp and tube worms living in the same place. Scientists had never been seen such a combination anywhere else on Earth.

An abundance of Rimicaris sp. shrimp are clustered around an area of diffuse flow at the Von Damm vent site. These shrimp are about 10 centimeters long and eat chemosynthetic bacteria that are grown on their own bodies. There are also some zoarcid eelpout fish seen among the shrimp. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011.

Green eggs can be seen on this alvinocarid shrimp living near a hydrothermal vent at the Von Damm site. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011.

German said the advent of telepresence on the Okeanos changed the way he conducted science at sea.

“This is the future of telepresence where the people on shore can have the same insight as the people on the ship,” German said. “The only difference is the people on the ship have less time to think about it because they are they are putting on their boots and worrying about how to position the equipment. The people on shore were just thinking about the data. This was revolutionary idea.”

German said the 2011 cruise to the Mid-Cayman Rise also has informed his work since then, providing insights about where chemosynthetic life could arise on other worlds, such as Jupiter’s moons Europea or Enceladus. In fact, German is headed to the Arctic Ocean next month on a joint NOAA-NASA cruise to test both technology and scientific principles that could help discover extraterrestrial marine life. Now that would be lucky.