A vintage photograph of the USS S-Five. Image, courtesy Naval Historical Foundation. Click image for larger view.

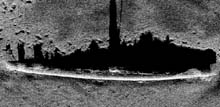

The S-Five as it appears in a sonar image with an exaggerated shadow. Click image for larger view.

History of the USS S-Five Submarine*

Laura Rear

Marine Archaeology Assistant

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

The S-Class submarine USS S-Five was built in Kittery, ME, from 1917 to 1920, a period when the U.S. Navy was testing the performance capabilities of civilian boatbuilders. The Navy’s largest submarine at the time, it was 231 ft long and displaced 870 tons. On May 6, 1920, Captain Charles “Savvy” Cooke, Jr., took command of the submarine. That summer, the S-Five passed its sea trials even though the Bureau of Construction and Repair was aware that the submarine had a faulty induction valve, part of the system that circulated fresh air inside the sub.

With sea trials behind it, the sub was ready to complete its first assignment, a recruitment mission to Baltimore, MD, and points south. During the mission, the sub was to perform the last of its endurance tests, including a 24-hour surfacing, followed by a dive to 50 ft, another surfacing, a high-speed run, and finally, a crash dive. All was well aboard the S-Five until the crash dive in the early afternoon of Sept. 1, about 50 mi off the coast of Cape May, NJ. About 20 seconds after its initial descent, the sub began to take on water. The Chief of the Boat, Percy Fox, had forgotten to close the main induction valve. Water was coming in everywhere and there was little the men onboard could do. The sub hit the bottom of the sea floor, 180 ft below the surface, within 4 minutes.

Attempts to raise the sub from the sea floor failed, as did attempts to use the three bilge pumps on board. Savvy made one last attempt to get the sub to the surface; he decided to blow the aft ballast tanks. As he did this, the submarine’s stern lifted off the bottom of the sea floor. Anything that wasn’t tied down began falling toward the bow, including people. Eventually, the sub stopped moving; its bow was in the sea floor and its stern protruded from the water surface.

Men were trapped in rooms with noxious chlorine gas fumes. As time passed, and death seemed imminent, a crew member heard waves breaking over the sub’s hull. After realizing that the stern was out of the water, Capt. Cooke decided to drill an escape hole in the hull. Some 16 hours later, he was able to peek out at passing ships through a 6" x 8" hole.

On Sept. 2, the ALANTHUS, a wooden steamship on its last voyage, spotted a small, dark object on the horizon and announced it as a fishing boat. A few minutes later, however, the crew noticed a white rag waving from the object. As they got closer they realized it was the stern of a submarine, so Captain Johnson of the ALANTHUS sent out a small boat to examine the situation. He was soon speaking back and forth with Capt. Cooke, and decided to tie the sub to his ship. The ALANTHUS crew pumped compressed air into the S-Five and passed buckets of water down into it. The drilling to free the submarine crew continued well into the evening.

At the same time, a ship called the GEOTHALS was making its way home to New York from Haiti, and answered distress flags being flown by the ALANTHUS. The GOETHALS radioed to shore that the S-5 had sunk and needed help. Within hours, numerous ships were en route to rescue the submarine. At 1:15 am on Sept. 3, the escape hole was finally finished. By 3:34 am, all of the submariners had been rescued and were receiving treatment aboard the ALANTHUS. Capt. Johnson's decision to tow the S-Five was a mistake, however. The cables snapped and sent the submarine to the sea floor about 15 mi off of Cape May.

*Adapted from A.J. Hill, "Under Pressure: The Final Voyage of Submarine S-Five." 2002. New York: The Free Press.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.