by Marta Miatta, Memorial University of Newfoundland

June 16, 2017

Incubation of mud core samples post-dive in order to study feeding rates of benthic organisms. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 623 KB).

I am Marta Miatta, a PhD student at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada. I work with Dr. Paul Snelgrove and my project aims to clarify the processes occurring in deep-sea sediments and the role that different animals play. This is my very first oceanic expedition and I could not be more excited!

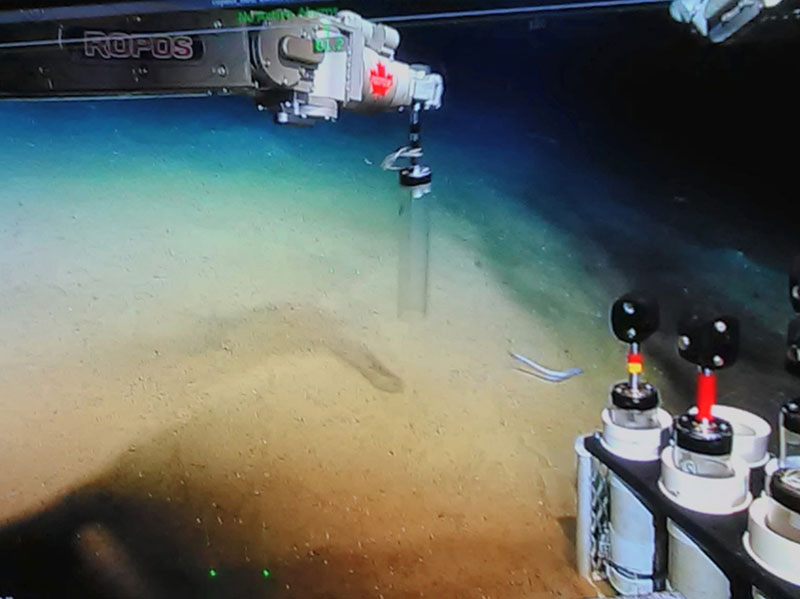

I am on this cruise to collect samples of soft sediment, usually fine muds, from different habitats on the seafloor. The ROPOS team is doing an amazing job collecting these samples using a robotic arm to insert our plastic core tubes into the seafloor to collect the sediment. The other scientists affectionately call us “the mud people.”

Working on mud may not seem appealing to everyone because mud fields often appear as deserts and, except for the presence of a few fish swimming by and brittle starfish crawling around, it seems as if nothing is going on. What many people do not realize is that these habitats are fascinating, cover most of the ocean floor worldwide, and are teeming with life. Most of this life is smaller than a few millimeters and requires a microscope to see. But once you look, you discover an entire world with lots of different organisms, from worms to shrimps, from shells to snails. These animals are collectively known as “benthic” organisms, meaning they live in or on the bottom, as opposed to “pelagic,” which refers to rest of the animals that live in the water column above the bottom. The benthic animals that live mostly on or above the sediment are known as “epifauna,” while those animals that live buried within the sediments are called “infauna.” Also, if the animals can only be viewed with a microscope, they are also called “microfauna” or “microbenthos,” while anything larger are known as “macrofauna” or “macrobenthos.”

The ROPOS’ mechanical arm obtaining a sediment core in Corsair Canyon, Canada. Depth around 1,000 meters. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 521 KB).

These soft bottom benthic habitats are also extremely important. The biological and geochemical processes in deep-sea sediments, including decomposition and recycling of nutrients, are crucial to our lives through the services that they provide (production of food and medicines, climate regulation and cleansing of water and air, and many others). Scientists believe these key processes directly connect to the biodiversity of the organisms that live in the sediment. However, the precise mechanisms are still unknown and require more studies to improve our understanding.

So here I am, playing in the mud every day, incubating the cores to see how the benthic animals and microbes recycle nutrients, and then evaluating the key players in making that happen. Once completed, I hope this work will inform management decisions that will help to protect our oceans.