by Joost Verhoeven, Memorial University of Newfoundland

June 15, 2017

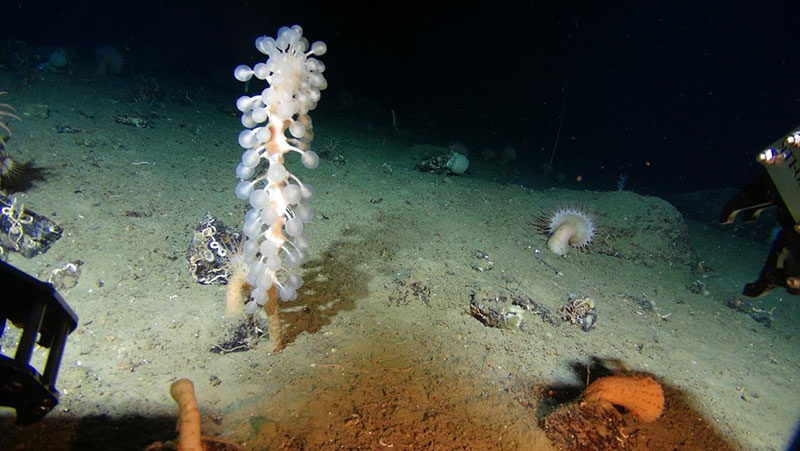

The carnivorous sponge Chondrocladia grandis off Baffin Island, Canada. Note the inflated spheres and how its main body protrudes into the sediment. Image courtesy of ArcticNet. Download larger version (jpg, 421 KB).

The main “attraction” during this scientific cruise onboard NOAA Ship Henry Bigelow is the beautiful and diverse deep-sea corals. While most people will be familiar with corals overall, the bottom habitats that make up the continental slope and the Gulf of Maine hold many other fascinating and lesser-known creatures. One of those is the enigmatic sea-sponge, Chondrocladia grandis.

To understand why Chondrocladia grandis is unique, we need to first introduce a small bit of sponge biology. Sponges are primitive animals and most have bodies that are made up of an intricate network of canals and pores through which water is pumped. As the water flows by specialized cells, tiny food particles such as bacteria and phytoplankton are transferred from the water to the inside of the sponge cells. This is called filter feeding and is what most sponges use to survive.

Close-up of one of the trapping spheres of Chondrocladia grandis. Inside is a prey animal attached to the sphere. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 114 KB).

However, Chondrocladia grandis is unique in that it does not filter feed. Instead, they are carnivorous sponges. They prey on small animals such as copepods, which are planktonic crustaceans that live near the seafloor. To accomplish this, these sponges have a very curious layout: they stand upright, half buried in the marine sediment, and have large inflatable spheres attached to them, covered with a sticky material and hooks comparable to Velcro. When prey comes along and touches the sponge, they get stuck to these spheres. As the prey tries to escape, the ensuing struggle only entangles them more. Eventually, the sponge will form a small layer of cells around the prey, totally engulfing and internalizing the prey in their body where digestion will occur.

In general, sponges are a “metropolis” of bacteria. That is, a lot of different bacteria can reside within sponges and are known to live there in symbiosis. Simply put, the sponge provides shelter and access to nutrients, while the bacteria provide the sponge with products they cannot synthesize themselves. We believe that symbiotic bacteria are a key component in enabling sponges to engage in carnivorous behavior. These bacteria may be crucial to digestion by creating chemical products that aid in breaking down complex molecules found in the prey so that these compounds become available for the sponge to use as food.

Smile for the camera! The successful retrieval of a Chondrocladia grandis specimen on board the CCGS Amundsen in the Canadian Arctic, 2015. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

During this cruise, we hope to find several carnivorous sponge specimens so we can get a better idea of the sorts of environments where these sponges flourish and also get some high-definition pictures in the hopes that we can identify specimens that have recently been feeding.

Several individuals will be collected by the ROPOS remotely operated vehicle and studied in the lab, where we can identify all the different bacteria that are present within these carnivorous sponges. These bacterial investigations will give us a better idea of the symbiotic interactions occurring between the bacteria and the sponge and how Chondrocladia grandis manages to survive in the cold, dark depths of the Atlantic Ocean.