By Steve Ross, Research Professor - University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Center for Marine Science

Sandra Brooke, Associate Research Scholar - Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory

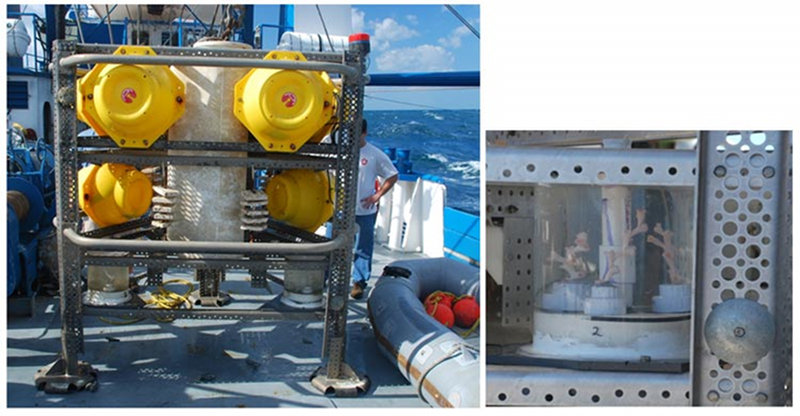

A lander does not float very high and can be difficult to spot at sea. This UNCW lander had been on the bottom for a year and came to the surface close to the ship and was easily found. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross (UNCW). Download iamge (jpg, 83 KB).

It is always traumatic to deploy very expensive science gear into the marine environment. Fishermen, members of the military, or anyone who uses the ocean can sometimes lose gear. For us, this risk is perhaps even more troublesome because in addition to perhaps loosing equipment worth many thousands of dollars, we also lose invaluable data and experiments. But, if we do not take these risks, we will learn nothing and the quest for knowledge that will help us understand and manage our ecosystems is of vital importance.

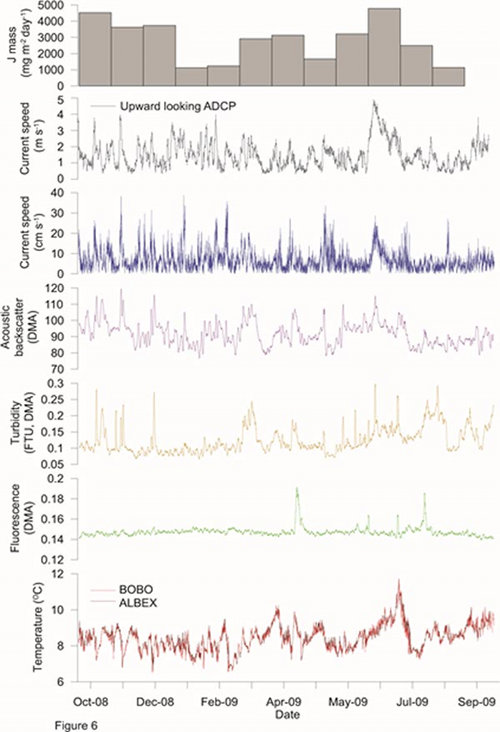

Examples of the intense and huge volume of data produced during a one year lander deployment at 480 meters in the Gulf of Mexico. Note the high variability in many of these variables, indicating a very dynamic environment. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross (UNCW). Download image (jpg, 63 KB).

Benthic landers and moorings are widely used and are valuable for collecting data that are otherwise unavailable. They can accommodate biological experiments and a variety of instruments, gathering unique, intense data streams. Two benthic landers provided by our Dutch colleagues at NIOZ, two provided by the University of North Carolina-Wilmington (UNCW), and two moorings provided by the U.S. Geological Survey, have now been down in Baltimore and Norfolk canyons for over eight months.

All of this equipment is scheduled to be recovered during a short cruise in August 2013. However, on this May cruise we intend to recover the two UNCW landers, recover coral growth experiments, download the data, and then redeploy them until the August pick-up. This is a simple process as long as everything works!

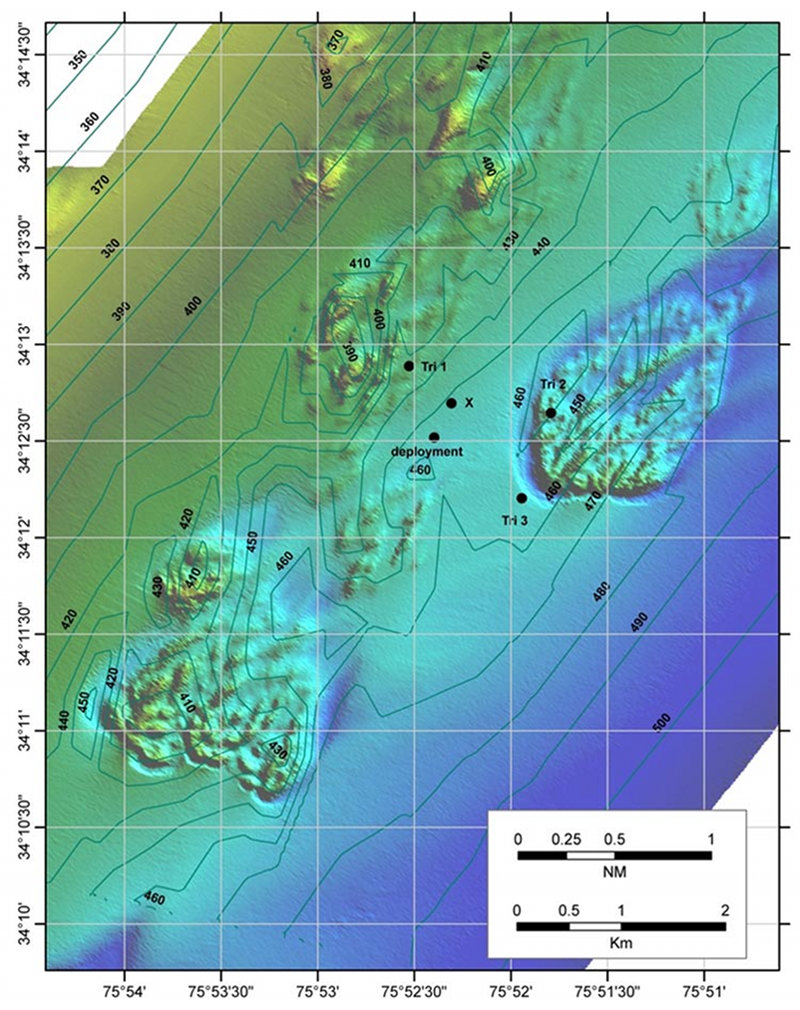

Soon after each lander hits the bottom during last year’s cruise, we moved the ship to three locations around the lander to triangulate its position (see map) by getting range data from signals to its acoustic releases. This gave us an approximate position of the lander on the bottom.

Multibeam sonar map of a deep-sea coral area off Cape Lookout, North Carolina. The black dot near the center marked "deployment" is the surface position where a benthic lander was dropped. Three dots marked "Tri 1-3" are surface locations used to take range data to the lander. The dot marked "X" is the bottom position for the lander calculated from the range triangulations. Image courtesy of Mike Rhode and Steve W. Ross (UNCW). Download image (jpg, 213 KB).

When we return to recover the lander, we hover over its calculated position and signal its acoustic releases again. When communication is established, we tell the release to drop the 600-pound weight that anchors the lander to the seafloor. By constantly pinging the lander for its range, we can tell if it is rising off the bottom. Sometimes a release may fail, and for that reason, all of our landers have a back-up release which can be used to drop the weight.

If the lander is rising, we have everyone on the ship stand by to scan the ocean in all directions. We ask the ship stay as close to the site as possible, but obviously we must move away a short distance to prevent the lander from hitting the bottom of the ship. We never know exactly where the lander will surface, since our ranging equipment is less accurate when the lander is near the surface.

There is a red flag on the lander that will help us spot the lander (but sometimes these flags are lost), as do the yellow floats and a trailing float line (see picture of lander on the surface). Although we try to bring landers up in the daylight when visibility is best, our landers have pressure and light activated strobes and a radio direction beacon to assist locating them. Even with these aids, rough seas can really interfere with finding a lander, so some landers have Iridium or other satellite transmitters which can send a message, including its location, to an owner.

A UNCW lander after one year on the bottom in 400 meters (left). Image courtesy of S.W. Ross (UNCW) and S. Brooke (FSU). Download image (jpg, 35 KB).

Once we see the lander, then all other recovery work is more routine with the ship steaming alongside the lander, grappling its recovery line, and using a crane or stern frame to lift the lander on board. Of course, rough seas can complicate this phase as well.

Once safely tied down to the ship, the tasks of cleaning, taking off instruments and data, and recovering experiments begins.