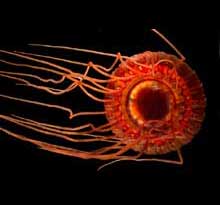

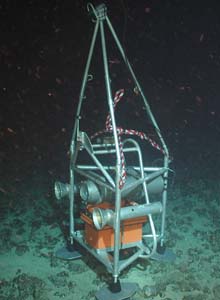

Fig 1: Eye-in-the-Sea. LED illumination source is at the top of the tripod. The camera bottle is the large gray cylinder with an optical port at the end. Just beneath the camera is the orange battery box. The flanged tubes to either side of the camera are lift points, into which the “stabs” on the front of the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible slide. The ends of the “stabs” are visible at the bottom of the image. Click image for larger view and credits.

Eye in the Sea

Edith A. Widder, PhD

Senior Scientist

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution

How many animals are there living in the vast depths of the ocean that remain unknown? How many have we never glimpsed because they outrun our nets and avoid our bright and noisy submersibles? The Eye-in-the-Sea (EITS) (Fig 1) was designed to address these questions. The EITS is a programmable, battery-powered camera and recording system that can be placed on the sea floor and left for 24 to 48 hours to observe the animal life in the dark depths with as little disturbance as possible.

To observe nocturnal animals on land, investigators use invisible infra-red light and infra-red sensitive cameras. It’s not so easy in the ocean. Infra-red light is absorbed too rapidly in sea water; It provides inadequate illumination of large animals, when used with standard infra-red sensitive cameras. To compensate for this the EITS uses an exceptionally sensitive intensified camera. In addition the illumination source, which is an array of Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs), uses far-red light that travels further through seawater than infra-red light.

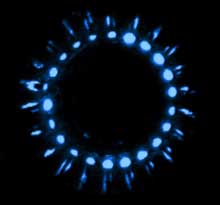

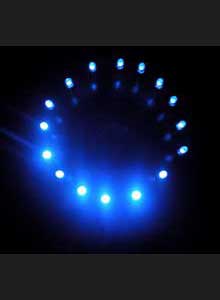

Fig 3: Electronic jellyfish (e-jelly) constructed of a ring of blue Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs). Click image for larger view and credits.

This light is dimly visible to the human eye, but invisible to deep-sea dwellers that are adapted to see primarily blue light. The camera and recording system are housed in a “bottle” – a cylindrical can with an optical port, designed to withstand the crushing pressure at depths of up to 3000 feet (more than 1300 pounds per square inch!). The light is mounted on a tripod, off-axis from the camera, in order to minimize backscatter from particles in the water. A lead-acid battery like those used in cars, but in an oil-filled pressure housing, provides the power (Fig 2).

The EITS can be programmed to turn on its red light and record video at

regular intervals. Alternatively it can be programmed to record

when its very sensitive light detector, called a photomultiplier tube,

sees a bioluminescent flash. The flash triggers the camera to record

3 seconds of video with the lights out, in order to record the luminescence,

and then turns on the red light to reveal the source of the light (![]() Video

Clip 1: Animation by Jon Saint).

Video

Clip 1: Animation by Jon Saint).

During Deep Scope 2004 we used both bait and an electronic jellyfish (Fig

3) to attract animals to the EITS. The e-jelly was designed to imitate

the bioluminescent burglar alarm display of the common deep-sea jellyfish Atolla (Fig

4 and ![]() Video Clip 2).

Video Clip 2).

This display is called a “burglar alarm” because

it is meant to attract attention, just as a burglar alarm does. If

the jellyfish is caught in the clutches of a predator its only chance of

escape is to “call” for help with its eye-catching light

display i.e. attract the attention of a bigger predator that may attack

their attacker, thereby affording the jelly the chance of escape. We

have evidence that certain fish are attracted to the e-jelly (![]() Video

Clip 3) and during

Deep Scope 2004 our most exciting recording, of a squid so new to science

that it can’t even be placed in a known family (

Video

Clip 3) and during

Deep Scope 2004 our most exciting recording, of a squid so new to science

that it can’t even be placed in a known family (![]() Video

Clip 4), was captured just after the e-jelly burglar alarm display began. Unfortunately,

the e-jelly was just out of the field of view in this recording, so we

can’t say definitively that the squid was attacking it. To

address this problem an “at-sea fix” was kluged together

out of an old aluminum ladder to maintain the bait and the e-jelly in

the field of view of the camera (Figs 5-7). Dubbed the C.L.A.M. for Cannibalized

Ladder Alignment Mechanism this fix proved so effective (

Video

Clip 4), was captured just after the e-jelly burglar alarm display began. Unfortunately,

the e-jelly was just out of the field of view in this recording, so we

can’t say definitively that the squid was attacking it. To

address this problem an “at-sea fix” was kluged together

out of an old aluminum ladder to maintain the bait and the e-jelly in

the field of view of the camera (Figs 5-7). Dubbed the C.L.A.M. for Cannibalized

Ladder Alignment Mechanism this fix proved so effective (![]() Video

Clip 5) that it has now been made a permanent part of the EITS in a more stream-lined form (Fig 8).

Video

Clip 5) that it has now been made a permanent part of the EITS in a more stream-lined form (Fig 8).

A new version of the Eye-in-the-Sea is now under development. This new system is being designed to go on a deep-water mooring in the Monterey Canyon. Because the mooring will provide power, we will no longer be limited to 48-hour deployments. The Eye-in-the-Sea will be able to collect data continuously for months at a time and stream the video to shore. Finally we will have a window into the deep-sea, one that we hope will allow us to view animals and behaviors never seen before.