1867-1868

Louis F. de Pourtales conducts dredging operations from the Coast Survey Steamers Corwin and Bibb off southern Florida in water depths to 517 fathoms and finds prolific life extending below 300 fathoms.

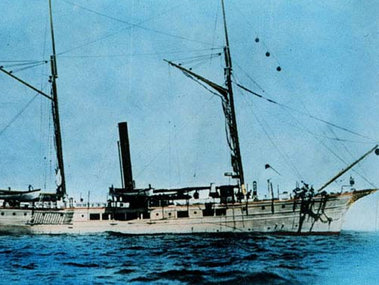

The Coast Survey Steamer Bibb. Image courtesy of NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 52 KB).

1868-1869

Wyville Thomson dredges from the HMS Lightning and Porcupine and discovers life as deep as 2,400 fathoms, exploding forever Edward Forbes' theory of a lifeless (azoic) zone below 300 fathoms.

1871

Spencer Fullerton Baird is appointed the U.S. Commissioner of Fisheries. The following year, he uses the Coast Survey Steamer Bache to dredge along the continental slope of New England. This is the first oceanic research conducted by the U.S. Fisheries Commission, forerunner of today's NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service.

1872

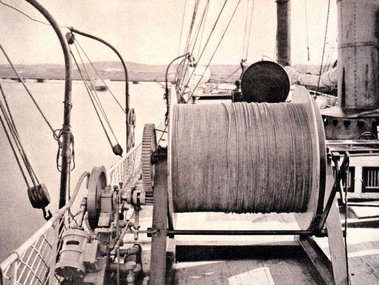

Sir William Thomson invents an operational wireline sounding machine. Modifications of this machine ultimately replace hemp-rope sounding methods. The wireline machines are faster to operate and significantly more accurate.

The Coast Survey Steamer Hassler proceeds from the U.S. East to the West Coasts via the Straits of Magellan and attempts deep-ocean dredging and other deep-sea operations along the way. The expedition is led by the famous naturalist Louis Agassiz, accompanied by Louis F. de Pourtales. Unfortunately, the hemp dredge line is defective and breaks on every deep dredging attempt. Although deep dredging operations fail, the cruise is generally successful, as Louis Agassiz collects more than 30,000 specimens of sea life.

The Coast Survey Steamer Hassler. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 32 KB).

1872-1876

The Challenger Expedition circumnavigates the globe in the first great oceanographic expedition. Research is conducted on salinity, density, and temperature of sea water, as well as ocean currents, sediments, and metrology. Hundreds of new species are discovered and underwater mountain chains documented. Modern oceanography is based on this research.

Sir Wyville Thomson leads the British Challenger expedition, the first worldwide oceanographic cruise. Thomson dies before all of the results are compiled. Sir John Murray finishes the great work, publishing 50 volumes of the Challenger's results and discoveries.

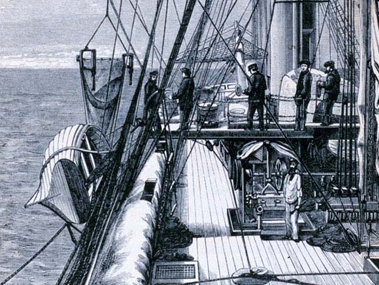

Dredging and sounding equipment on the H.M.S. Challenger. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 143 KB).

1872-1878

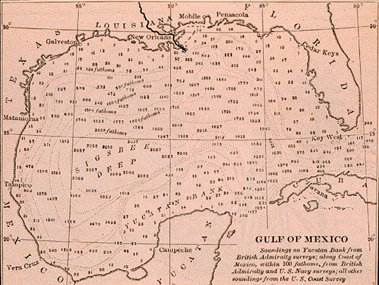

Accurate, high-density soundings taken by the Coast Survey Steamer Blake in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea lead to the first modern bathymetric map.

The first modern bathymetric map was created from soundings made in the Gulf of Mexico. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 72 KB).

1873-1874

The USS Tuscarora, under Commander George Belknap, uses a Thomson sounding machine on a telegraph cable to survey across the Pacific Ocean between Cape Flattery, Washington, and Japan. Belknap discovers the Juan de Fuca Ridge, indications of seamounts, and indications of the Aleutian Trench and Japan Trench.

1874-1877

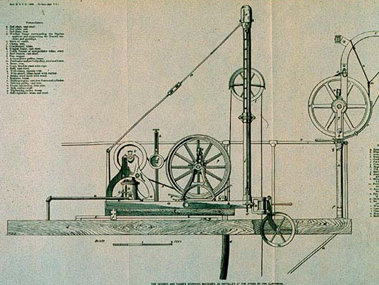

Commander Charles D. Sigsbee commands the Coast Survey Steamer Blake. Sigsbee modifies the Thomson sounding machine and designs an instrument termed the Sigsbee sounding machine. This becomes the basic model for wireline sounding in the deep sea for the next 50 years.

Diagram of the Sigsbee sounding machine from 1875. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 58 KB).

1875

On November 6, the USS Gettysburg, under Captain H.H. Gorringe, discovers an undersea mountain 130 miles west of the coast of Portugal, between the Azores and the Straits of Gibraltar. The discovery occurs as the ship is conducting sounding operations with a Thomson sounding machine. It is not the first undersea mountain to be discovered, as the Tuscarora had sounded on a number of seamounts west of Hawaii in early 1874; however, the Gettysburg researchers devoted particular effort to determining least depth. Originally called Gorringe Bank, and noted with a least depth of 33 fathoms, the area is now termed Gorringe Ridge and is known to have two peaks, Gettysburg Seamount and Ormond Seamount.

1877

The Coast Survey Steamer Blake is the first ship outfitted with steel rope for dredging and other oceanographic purposes, as a result of collaboration between Alexander Agassiz and Charles D. Sigsbee.

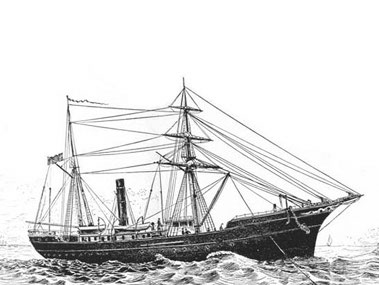

The Blake was the first ship to use steel wire for dredging and anchoring. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 61 KB).

1882

The U.S. Fisheries Commission Steamer Albatross — the first vessel built by any government from the keel up as an oceanographic research vessel — begins operations.

1885

The Coast and Geodetic Survey (as the Coast Survey was renamed in 1878) Steamer Blake, under Commander John Elliott Pillsbury, pioneers deep-ocean anchoring techniques during Gulf Stream studies. The Blake is reported to have anchored in 2,200 fathoms.

John Elliott Pillsbury pioneered the use of deep-sea anchoring aboard the Blake. Image courtsey of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 46 KB).

1899-1900

The Fisheries Commission Steamer Albatross, under Alexander Agassiz, makes an extended cruise into the south central Pacific, conducting sounding, dredging, and water temperature observations.

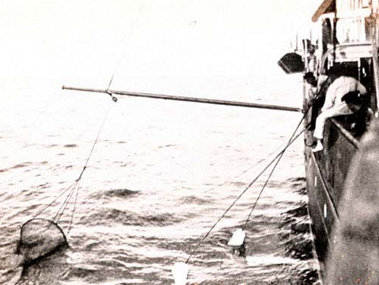

Plankton tow and dip nets on the Albatross were used to collect marine life. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library. Download larger version (jpg, 42 KB).

1904-1905

The Fisheries Commission Steamer Albatross, under Alexander Agassiz, makes a second extended cruise in the south central Pacific, acquiring data in some of the most remote stretches of ocean on Earth. Sir John Murray says of these explorations, "Of all the additions to our knowledge of the depth and deposits of the Pacific Ocean during recent years, the most important are probably those acquired by Dr. Alexander Agassiz during his various cruises in the Pacific."

Scientists on the Fisheries Steamer Albatross discovered hundreds of marine species during expeditions throughout the world. Image courtesy of the NOAA Photo Library Download larger version (jpg, 47 KB).

1912

April 15, the White Star Liner Titanic sinks with horrendous loss of life after striking an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean. This leads to a concerted effort to devise an acoustic means of discovering objects in the water forward of the bow of a moving vessel.

1914

On April 27, Reginald Fessenden, of Submarine Signal Corporation, sails on the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Miami. He uses a Fessenden Oscillator to reflect a signal off an iceberg and simultaneously reflect an acoustic signal off the sea bottom. This test marks the beginning of the acoustic exploration of the sea.

1917-1919

World War I accelerates oceanic acoustic research as both the U.S. Navy and the Army Coast Artillery develop research programs to devise means to detect enemy submarines.

1919

French scientists succeed in running the first line of soundings obtained from an acoustic echo sounder.

1922

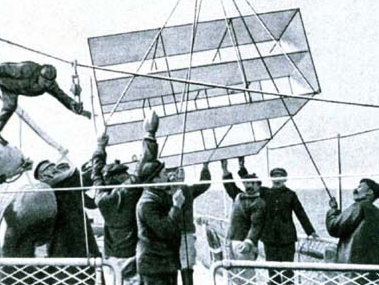

Prince Albert of Monaco sails for a number of years throughout the eastern Atlantic Ocean, making the first upper-air observations at sea using kites and weather balloons as well as numerous other oceanographic observations.

Explorers on the ship Princesse Alice launch one of the first weather kites. Prince Albert I of Monaco owned the ship and sailed it throughout the 1920s, pioneering studies of ocean-atmosphere interactions. Image courtsey of NOAA Photo Library Download larger version (jpg, 55 KB).