By Heidi Hirsh, Natural Resources Management Specialist - NOAA Fisheries Service, Marine National Monuments Program

Graduates and students of Kamehameha School onboard the Itasca, 4th expedition, January 1936. Back row, left to right: Luther Waiwaiole, Henry Ohumukini, William Yomes, Solomon Kalama, James Carroll. Front row, left to right: Henry Mahikoa, Alexander Kahapea, George Kahanu, Sr., Joseph Kim. Image courtesy of George Kahanu, Sr.; credit: Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 368 KB).

Would you want to volunteer to live on an uninhabited tropical island for three months at a time – with no contact with the outside world? It may sound great, but know that the environmental conditions can be harsh, with fresh water available only for drinking, and food brought in by ship. Would you be invigorated by the challenge or succumb to the isolation?

From 1935 to 1942, a group of 130 mainly Hawaiian men took on this challenge. They are known as Hui Panalāʻau, or "society of colonists." After the mid-nineteenth century guano-mining boom and guano depletion from a number of islands in the equatorial Pacific, the islands of Howland, Baker, and Jarvis sat relatively unnoticed until the 1930s. Military and commercial air routes between Australia and California then brought these islands to the attention of the United States. At that time, it was unclear who owned the islands. The advent of World War II — and the Japanese military's advancement across the Pacific — made it imperative for the United States to gain ownership of these islands.

To establish the three islands as U.S. territories, President Franklin D. Roosevelt needed to colonize them with permanent residents. But colonizing the islands with active duty military personnel would have violated international law. President Roosevelt sought instead to colonize the islands with furloughed military personnel and Native Hawaiian civilians. He appointed William T. Miller, Superintendent of Airways at the Department of Commerce, to lead this colonization project. Miller met with Albert F. Judd, Trustee of Kamehameha Schools and the Bishop Museum, and the two agreed that the students and recent graduates of the Kamehameha School for Boys were ideal candidates because they could "fish in the native manner, swim excellently, handle a boat, be disciplined, friendly, and unattached."

On March 30, 1935, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Itasca departed from Honolulu Harbor in great secrecy. Six young Hawaiians, all recent graduates of Kamehameha Schools, were aboard with 12 furloughed army personnel. They had the task of occupying the barren islands of Howland, Baker, and Jarvis in teams of five for three months. Because the Hawaiians had performed so admirably, additional Kamehameha School alumni replaced the furloughed army personnel in June 1935. This left the islands under the exclusive occupation of Native Hawaiians.

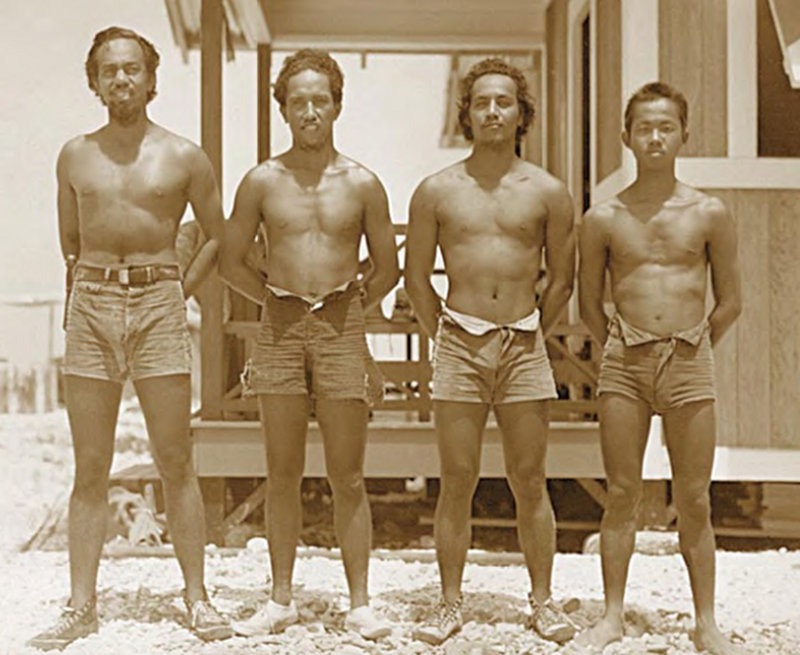

"Hawaiian Colonists—American Citizens. Kamehameha School Graduates." These words inspired the title of the 2002 Bishop Museum exhibit. Left to right, Solo-mon Kalama, Charles Ahia, Jacob Haili, and Harold Chin Lum, on Jarvis, 1937. Lum was not a K.S. graduate. Photo by W. T. Miller. Reproduced courtesy of the Bishop Museum. Download larger version (jpg, 288 KB).

The Hawaiian colonists' successful year‐long occupation enabled President Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 7368 on May 13, 1936. It proclaimed that the islands of Howland, Baker, and Jarvis were under the jurisdiction of the United States.

The duties of the colonists while on the island were varied. They included recording weather conditions, cultivating plants, maintaining a daily log, recording the types of fish that they caught, observing bird life, and collecting specimens for the Bishop Museum on O'ahu. In preparation of Amelia Earhart's arrival on Howland Island in 1937, the colonists constructed a landing field, bedroom, and shower (with a showerhead made out of a tomato can). They prepared a performance for her, but she never arrived. She disappeared in route to the island on July 2, 1937.

The personal sacrifice and hardship these young men endured is underscored by a 1938 tragedy. Colonist Carl Kahalewai's appendix ruptured while living on Jarvis Island. He eventually died during the five-day trip back to Honolulu aboard a U.S. Coast Guard ship.

In later years, the U.S. Department of the Interior oversaw the project and emphasized weather data collection and radio communication. This led to the recruitment of a number of Asian radiomen and aerologists. The project eventually expanded beyond the Kamehameha Schools to include Hawaiians and non‐Hawaiians from other schools in Hawaiʻi. These men thought that they were colonizing the islands for commercial airline use. Under this assumption, they surveyed birds and took meticulous daily records of weather and other environmental conditions.

On December 8, 1941, a fleet of Japanese twin‐engine bombers attacked Howland, Baker, and Jarvis Islands. They killed Hawaiian colonists Joseph Keliʻihananui and Richard "Dickey" Whaley. The United States had officially entered into World War II. As the country recovered from Pearl Harbor losses, retrieving the colonists was no longer a high priority. The December 8 attacks went unreported in Washington.

On March 20, 1942, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes sent letters of condolence to the Keliʻihananui and Whaley families. He stated, "In your bereavement it must be considerable satisfaction to know that your brother died in the service of his country.'' The letters subsequently urged the families to submit claims for compensation. However, in April 1942, the Keliʻihananui family's claim was denied because there were no "qualified dependents" to submit claims.

In 1954, the bodies of Joseph Keli‘ihananui and Richard "Dickey" Whaley were brought back to Hawai‘i and buried at Schofield Barracks on the island of O‘ahu. In December 8, 2003, they received proper burial at the Hawai‘i State Veterans Cemetery in Kāne‘ohe, Hawai‘i. They were honored with traditional Hawaiian ceremonial chants and performances for the work and sacrifice they made for the State of Hawai‘i and the United States of America.

The contributions and sacrifices of these young men established the Equatorial Pacific Islands as part of the United States. Their work set the stage for the islands' conservation status as National Wildlife Refuges and a Marine National Monument.

The 2010 documentary film, Under a Jarvis Moon , tells the incredible story of the Hui Panalā‘au. Co-directed by Noelle Kahanu and Heather Giugni, it is a tribute to Kahanu's grandfather, George Kahanu, Sr., and the other Panalā‘au members. It chronicles our important history, nearly forgotten, which Kahanu discovered in the archives of the Bishop Museum.