By Michael Studivan - Ph.D. Candidate - Florida Atlantic University Harbor Branch

April 29, 2014

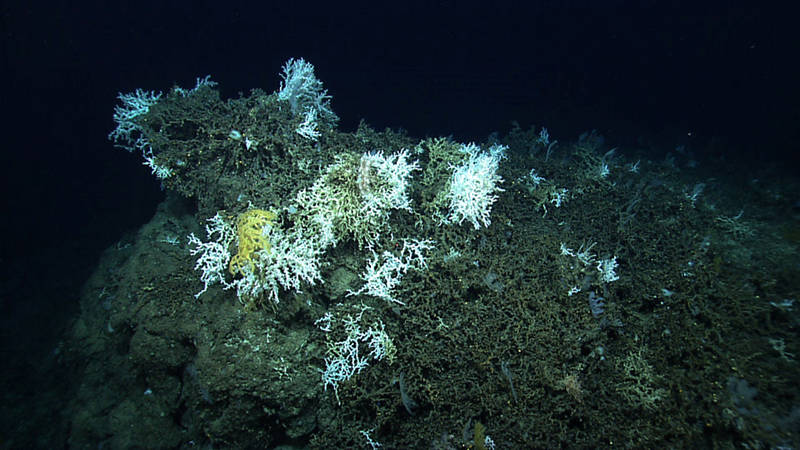

Live Lophelia pertusa colony. The white color is the skeleton showing through, as the tissue is clear. Notice the fleshy tentacles on each polyp. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Monday, April 28 was the first of the shallow dives on Lophelia pertusa reef sites named Many Mounds. Exploration of these reefs is one of the research priorities of the Cooperative Institute for Ocean Exploration, Research, and Technology (CIOERT) and Harbor Branch. As such, those of us at the Harbor Branch Exploration Command Center (ECC) are collecting data about benthic composition, density, and invertebrate diversity. In addition to inputting these data into our CIOERT database in real time, we are also capturing screenshots for data annotation and social media outreach.

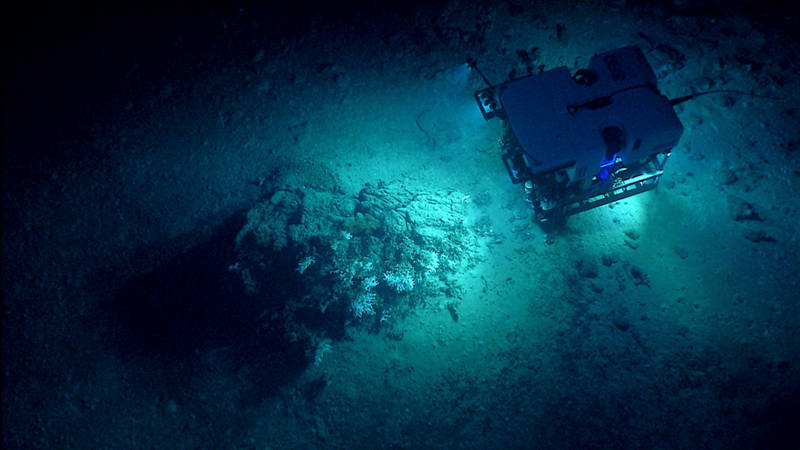

Deep Discoverer passing over a rock outcropping. Images courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

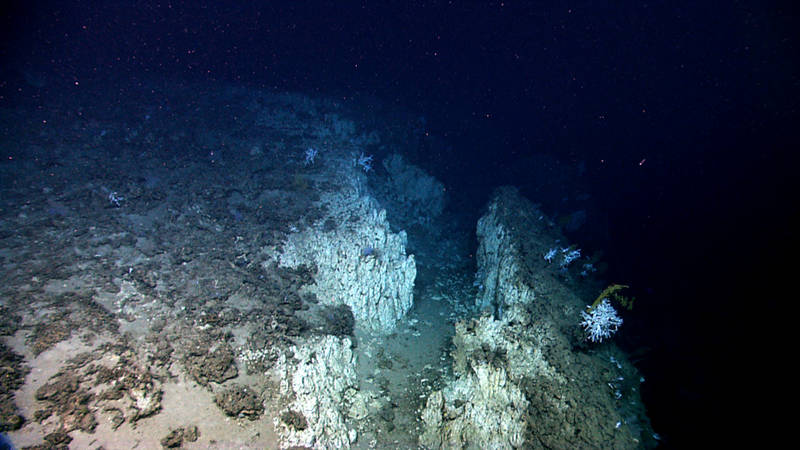

Recently fractured carbonate ledge with corals living on the margin. Images courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Lophelia is a fragile, scleractinian (reef-building) coral species that forms extensive reefs in deep water. This species does not have symbiotic zooxanthellae like many shallow water reef-building corals, and instead feeds on particles and planktonic animals.

Lophelia reef on a rock outcropping (bioherm). The live corals are white and are found most dense on the south side of the bioherm, due to predominant currents. Most of the rock is covered in dead coral rubble that browns over time. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

These reefs are threatened by human activities, notably deep-water fishing, where trawls and crab pots can destroy their delicate skeletons. This is especially detrimental, since Lophelia, like many deep-water species, grows about one millimeter a year and can live for hundreds to thousands of years. Protection of Lophelia reefs is therefore paramount for persistence of an ecosystem that supports a diverse assemblage of fish, crustaceans, corals, sponges, and other invertebrates (animals without backbones).

Most of the Lophelia reefs we saw today were built up on rock ledges and outcroppings, with extensive lower reef structures made out of dead coral rubble. We did see some relatively recent (~100 years) fracturing of carbonate ledges. Additionally, we saw a nice assortment of glass sponges, octocorals, and black corals, especially Aphrocallistes beatrix and Leiopathes.

Perhaps the coolest thing I saw was an urchin actively munching on a soft coral. We would not have seen it if not for the amazing zoom capabilities of remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer’s camera and the steady hand of the ROV pilots and videographers.

Pancake urchin eating a small octocoral colony. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

While my dissertation research is examining mesophotic coral reefs (30-150 meters), this cruise has been especially interesting and valuable for my growth as a graduate student and has given me the opportunity to experience an “at sea” research expedition. What strikes me the most is the live collaboration of the crew on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, all the ECCs around the US, individuals in the scientific community, and even members of the general public. We are able to accomplish so much more in terms of species identification and characterization of new deep-sea environments. After all, each group of scientists specializes in one field, yet in deep-sea exploration, there is a pairing of coral, invertebrate, and fish biology, geology, and geochemistry.

I hope that others out there, scientists and general public alike, have learned as much as I have about deep-sea reefs and our exploration capabilities.

For those of us prone to (ahem) minor seasickness, command centers like the one at Harbor Branch allow shoreside scientists to collect data and add to the major endeavor that is an oceanographic research cruise. In order to collect the high-quality data that we have been doing so far, we truly appreciate all the hard work and dedication of the ROV pilots and videographers, Okeanos Explorer crew, and shoreside scientists that make this all possible.