By Steve Ross, Research Professor - University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Center for Marine Science

Sandra Brooke, Associate Research Scholar - Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory

April 30 - May 27, 2013

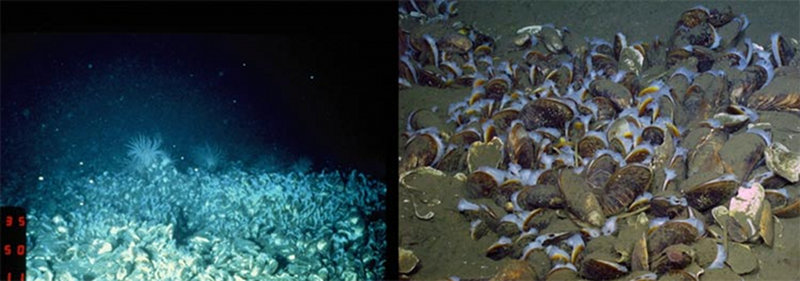

Images of the methane cold seep taken from a towed camera sled in 1981 (left) and from the ROV Kraken II camera in 2012 (right). These images illustrate the changes in camera technology over this time period. Images courtesy of B. Hecker, Hecker Consulting (left) and the Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS (right). Download image (jpg, 68 KB).

In the early 1980s, Dr. Barbara Hecker was the lead scientist on explorations of the canyons and slopes of the mid-Atlantic region, using towed camera sleds and the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible. She documented deep-sea corals on rugged hard-bottom near the heads of Baltimore and Norfolk canyons, including giant ‘bubblegum’ corals (Paragorgia arborea) and red tree corals (Primnoa resedeformis) and abundant smaller corals and other creatures.

After one of her towed camera surveys in Baltimore Canyon, she returned home and processed the film (real film, not digital files!), and in addition to the coral communities, she saw several frames with images of mussel beds. She deduced that these mussels indicated the presence of a methane cold seep, something that was unknown for the U.S. Atlantic coast at the time. It was quite a discovery, but the cruise was over, and she did not have an opportunity to return. Fast forward over three decades and the coral habitats and the seep have become targets of interest for our mid-Atlantic Deepwater Canyons project.

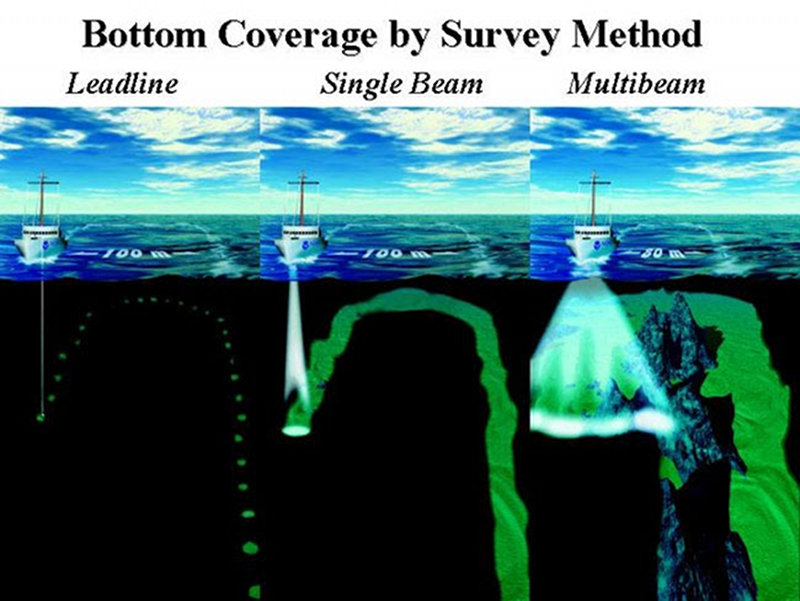

Changes in seafloor mapping technology have greatly improved our ability to conduct effective exploration and research, especially in the deep sea. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download image (jpg, 98 KB).

In 2011, we mapped several canyons and part of the slope using multibeam sonar, which provides a high-resolution image of the seafloor. Earlier scientists did not have this sophisticated tool to help them decide where to explore; they had only very coarse depth contours to guide them. Navigation technology has also changed a lot in 30 years; Dr. Hecker’s shipboard locations were logged using Loran C, and those numbers often were not as accurate as we need for locating sites. Her towed camera sled locations could only be estimated using shipboard positions and submersible navigation technology was not as accurate back then as it is today.

Despite these challenges, the historical information from Dr. Hecker and others was useful for helping us decide where in 2012 to deploy our primary research tool, the Kraken II remotely operated vehicle (ROV). We also used new multibeam maps to select what appeared to be rugged habitat within the historical survey areas. Using a combination of historical information and new technology, we gathered a large amount of fascinating and new insights into the biology, geology, oceanography, and archaeology of the canyons.

During our 2013 cruise, we will use the Jason II ROV (owned by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution), which can reach 6,500 meters and will make longer dives (16 hours per day) than last year. We will be investigating a potential new cold seep in deep water, in addition to re-visiting the ‘Hecker’ seep site we found last year. And we will, of course, continue to explore, document, and try to understand the different types of vulnerable marine communities in the deep canyons of the region.

In addition to more sophisticated at-sea technology, our analytical methods are also more advanced today than when these historical studies were done: We can use genetic and isotopic techniques to tell us how populations are structured and what the animals eat, we can study their physiology under a range of conditions to understand their distributions, and we can determine the age of the giant tree corals and derive information on past ocean conditions from their skeletons.

We still have a great deal to learn, but we have the tools to enable us to fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge, and with a little luck and a lot of hard work, this cruise will provide us with the data we need to better understand the canyon ecosystems.