By Amy E. Gusick, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara

April 20 - May 26, 2010

Watch/listen to a NOAA podcast on the Sea of Cortez 2010 expedition taking place in Ballena Bay just off the Isla Espíritu Santo. The project will begin with a sonar survey of the sea floor using both a side-scan sonar and a subbottom profiler, and will focus on the deeper-water portions in an attempt to identify features that can be tested for archaeological material. Through this endeavor scientists are hoping to identify and recover cultural material, identify and map the paleoshoreline and adjacent landscape, and collect intact terrestrial sediments and floral and/or faunal samples. Video courtesy of Amy Gusick, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, National Geographic Society/Waitt Institute for Discovery.Audio courtesy of Amy Gusick, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, National Geographic Society/Waitt Institute for Discovery. Download (mp4, 408.7 MB).Download Audio Podcast (mp3, 5.9 MB)

Audio courtesy of Amy Gusick, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, National Geographic Society/Waitt Institute for Discovery. Download Audio Podcast (mp3, 5.9 MB)

The manner and timing of the initial human migration into the New World has been a contentious archaeological issue for the better part of the last four decades. The first discovery of a projectile point associated with extinct megafauna began our assumption that the first inhabitants of the Americas were big game hunters. Because some of these first archaeological finds were discovered at sites located in the interior of North America, we assumed that theses early migrants followed their megafauna prey from Beringia, through a split in the ice sheets (an “ice-free corridor”) that covered North America at the end of the last ice-age. However, over the past decade numerous discoveries have led researchers to question our assumptions concerning the timing and pathway of this initial peopling of the New World. Among these discoveries are a 12,500-year-old site identified in coastal Chile, as well as numerous other 10,000-12,000 year-old sites identified along the coasts of both North and South America. These discoveries raise the question of whether the initial human migration into the New World occurred through an interior route of entry, through a Pacific coastal route of entry, or possibly by concurrent interior and coastal routes of entry.

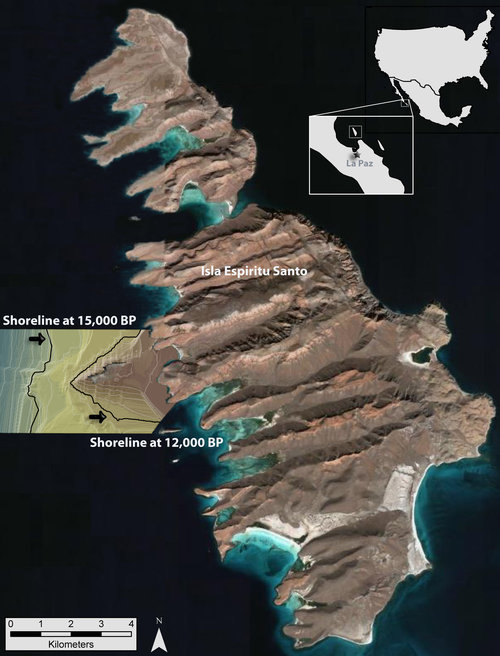

Aerial view of Isla Espíritu Santo merged with a digital elevation model of a section of the submerged landscape that shows locations of shorelines at 15,000 and 12,000 years ago. Image courtesy of Amy Gusick, Loren Davis, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 6.9 MB).

Although there has been much interest in a possible Pleistocene coastal entry, archaeological evidence that might serve to test this hypothesis has proven elusive thus far. The lack of progress towards the evaluation of a coastal migration hypothesis can be mainly attributed to the fact that thousands of miles of coastline, and any archaeological sites located on this coastline, have been submerged by sea level rise. Indeed, sea level has risen as much as 95 meters over the past 15,000 years in some areas along the Pacific Coast. Our project goal is to begin identifying some of these sites by investigating a submerged landscape off the western margin of Isla Espiritu Santo, located in the Gulf of California, Baja California Sur.

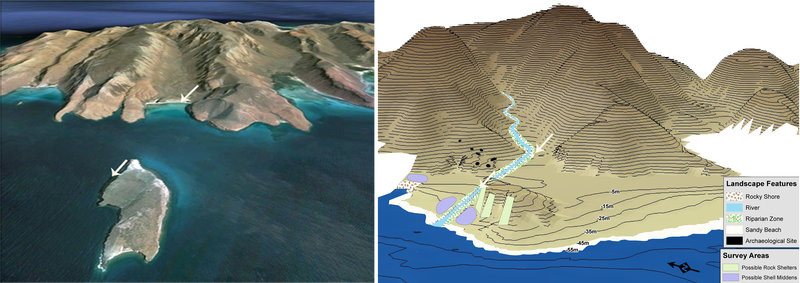

Left image shows landscape of Ballena Bay on Isla Espiritu Santo as it looks today. Right image shows paleolandscape model of the same bay as it may have looked 12,000 years ago, with sea level 55 meters lower than current sea level. Image courtesy of Amy Gusick, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, National Geographic Society/Waitt Institute for Discovery. Download larger version (jpg, 6.6 MB).

Our interest in this region was peaked by various factors. Previous archaeological research on the terrestrial portion of the island had yielded two 11,000 year-old habitation sites, indicating that humans were utilizing the landscape during the Late Pleistocene, a time period relevant to the initial migration into the New World. Prehistorically, as well as today, this area of Baja California is teeming with marine life, an important resource for maritime hunter-gatherers. This region of the southern Gulf of California also has exceptional potential for the preservation of inundated archaeological sites. The geology of the island presents numerous rock shelters and rock outcrops, two features that are known to attract the early maritime hunter-gatherer groups in which we are interested. Additionally, local oceanographic conditions contribute to the site preservation potential. Much like the Gulf of Mexico and the inside passages of the British Columbian archipelago, wave action in the Gulf of California is significantly reduced compared to the Pacific due to its protected position on the leeward side of the Baja California peninsula. These conditions should promote reduced erosion of the island’s submerged shelf and subsequent preservation of any archaeological sites it may hold.

Bob Jackson (left) and Loren Davis visit Covacha Babisuri, a Pleistocene-age archaeological site discovered by archaeologist Harumi Fujita on Isla Espiritu Santo. Image courtesy of Amy Gusick, Loren Davis, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 2.8 MB).

Members of the field crew hike down to the beach at Ballena Bay after excavating J69E, an 11,200-year-old archaeological site on Isla Espiritu Santo. Image courtesy of Amy Gusick, Loren Davis, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 2.9 MB).

Therefore, in 2007, our team developed a model of a portion of the submerged landscape of Isla Espiritu Santo that included a paleoriver channel, proposed rock shelter locations, and areas considered to have a high potential for yielding preserved archaeological material. In 2008, we conducted a scuba survey to ground-truth the model and to identify areas for further study. This survey revealed that our model accurately identified areas that contained rock shelters, and one high-potential location in which we identified a few pieces of ancient cultural material; however, this material was not located on a landscape deep enough to be associated with a Pleistocene migration into the New World. Nonetheless, these positive results encouraged us to continue our exploration into deeper-water portions of our study area.

Our 2010 fieldwork will focus on these deeper-water portions in an attempt to identify features that we will test for archaeological material. We will also collect samples to gather data pertaining to the geology and geomorphology of the submerged landscape. This information will allow us to understand the changes that have occurred on the landscape over the last 15,000 years and will also provide environmental data to enable us to target our search to those areas that would have produced the types of resources early maritime hunter-gatherers would have collected.

Loren Davis stands on top of an exposed relict coral reef dating to the last interglacial (~125,000 BP) on Isla Espiritu Santo. Image courtesy of Amy Gusick, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, National Geographic Society/Waitt Institute for Discovery. Download larger version (jpg, 2.7 MB).

Amy Gusick collects samples from a test pit 60 ft. below sea level. Image courtesy of Amy Gusick, Sea of Cortez 2008 Expedition, National Geographic Society/Waitt Institute for Discovery. Download larger version (jpg, 4.2 MB).

Our project will begin with a sonar survey of the sea floor using both a side-scan sonar and a subbottom profiler. The side-scan sonar and sub bottom profiling systems will run concurrently in order to identify targets from a surficial and sub-sediment perspective. Images collected from these systems will be used to identify “targets” that we will explore and sample during the subsequent scuba survey. The images collected from the sonar phase will also be used to create a detailed map of the entire island landscape as it would have been 15,000 years ago. This type of imagery can be very useful in understanding the geomorphological and environmental changes that have occurred since the Last Glacial Maximum and in understanding the effect of sea level rise on the landscape.

Expected outcomes of this endeavor are identification and recovery of cultural material, identification and mapping of paleoshorelines and adjacent landscape, and collection of intact terrestrial sediments and floral and/or faunal samples. We have high expectations for recovery of cultural material dating to the Pleistocene time period. Discovery of archaeological material on submerged Pleistocene landscapes in this region of Baja California will confirm that hunter-gatherer groups were present along the eastern Pacific shoreline at a time period relevant to an initial human migration into the New World. The lack of knowledge about the potential distribution of early sites on near-shore portions of the continental shelf is a significant obstacle to First Americans research today. Not only can the discovery of inundated early sites provide some of the most important information to evaluate the issue of coastal migration, but a more comprehensive understanding of submerged sites may also clarify New World archaeological chronology in general.